Therapy based on embryonic stem cells improved patients’ vision

- Share via

Two patients with vision problems who received injections of retinal cells made from human embryonic stem cells have seen marked improvement in their vision four months later, according to a preliminary study on the safety and efficacy of the pioneering treatment.

The report, published online Monday in the journal Lancet, is the first to describe results of an actual treatment derived from human embryonic stem cells. The patients -- one with dry age-related macular degeneration and the other with a pediatric version of the disease called Stargardt’s macular dystrophy -- were treated at UCLA over the summer. The therapy was developed by Advanced Cell Technology Inc., and the company funded the study.

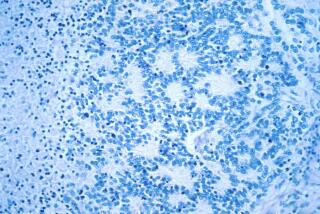

Both diseases cause patients to lose their central vision. They can be traced to problems with photoreceptor cells in the retina. The idea is to replace those faulty cells with new retinal pigment epithelium, or RPE, cells, which are grown from embryonic stem cells.

And that’s exactly what the researchers did. Both patients received about 50,000 new RPE cells in one eye, leaving the other eye to serve as a control. Since this was a phase 1 safety study designed to make sure the treatment wasn’t harmful, the dose was intentionally low. But after four months, both patients showed tangible signs of improvement, according to the Lancet report.

Before the injection, the patient with macular degeneration had 20/500 vision. (Perfect vision is 20/20.) Now the patient’s vision is 20/320. That improvement corresponded to being able to read 33 letters on an eye chart instead of only 20.

For the patient with Stargardt’s macular dystrophy, the treatment made it possible for the patient to count fingers held in front of her. Previously, the best she could do was discern hand motions.

In an editorial that accompanies the study, Dr. Anthony Atala, director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Wake Forest University, wrote that “the results are impressive -- especially considering the progressive nature of both diseases. Also of importance is that the patients were part of a phase 1 safety study, and the lowest dose was not only safe but seems to be effective for the duration of the 4-month follow-up.”

Being a safety study, researchers were on the lookout for signs of trouble. One concern about stem cells is that they can grow into tumors called teratomas. None have been found in these two patients, and they tend to appear within eight weeks, according to the study.

The researchers did find one transplanted RPE cell in the Stargardt’s patient that appears to have wandered beyond its intended home and parked itself on the surface of the retina. So far, it doesn’t seem to be causing any trouble there, according to the report.

Still unknown is whether the RPE cells would be rejected if the patients stopped taking their immunosuppression drugs, or whether the vision gains will last. It’s possible that additional injections could be necessary to maintain the benefits observed so far, the researchers wrote.

But the take-home message for Atala was how quickly scientists at Advanced Cell Technology managed to turn a discovery in the lab -- the isolation of the first human embryonic stem cells by James Thomson in 1998 -- into a clinical therapy. Fourteen years may seem like a long time to patients who have been counting on stem cells to deliver cures for ailments like diabetes, Parkinson’s disease and spinal cord injuries. But it took longer than that -- 17 years-- for Thomson to derive human embryonic stem cells after the mouse version of these cells were made in 1981.

The study is online here. The editorial is here.

Return to the Booster Shots blog.