App promises to direct dreams

- Share via

Suppose you could order a dream as easily as you can order a pizza — except that it would be free.

“Dream on!” you might say, unless you know about Dream:On. That’s the iPhone app for made-to-order dreams that has been something of a sensation since it was introduced at Scotland’s Edinburgh International Science Festival in April. (In just the first week, it was downloaded more than 300,000 times.)

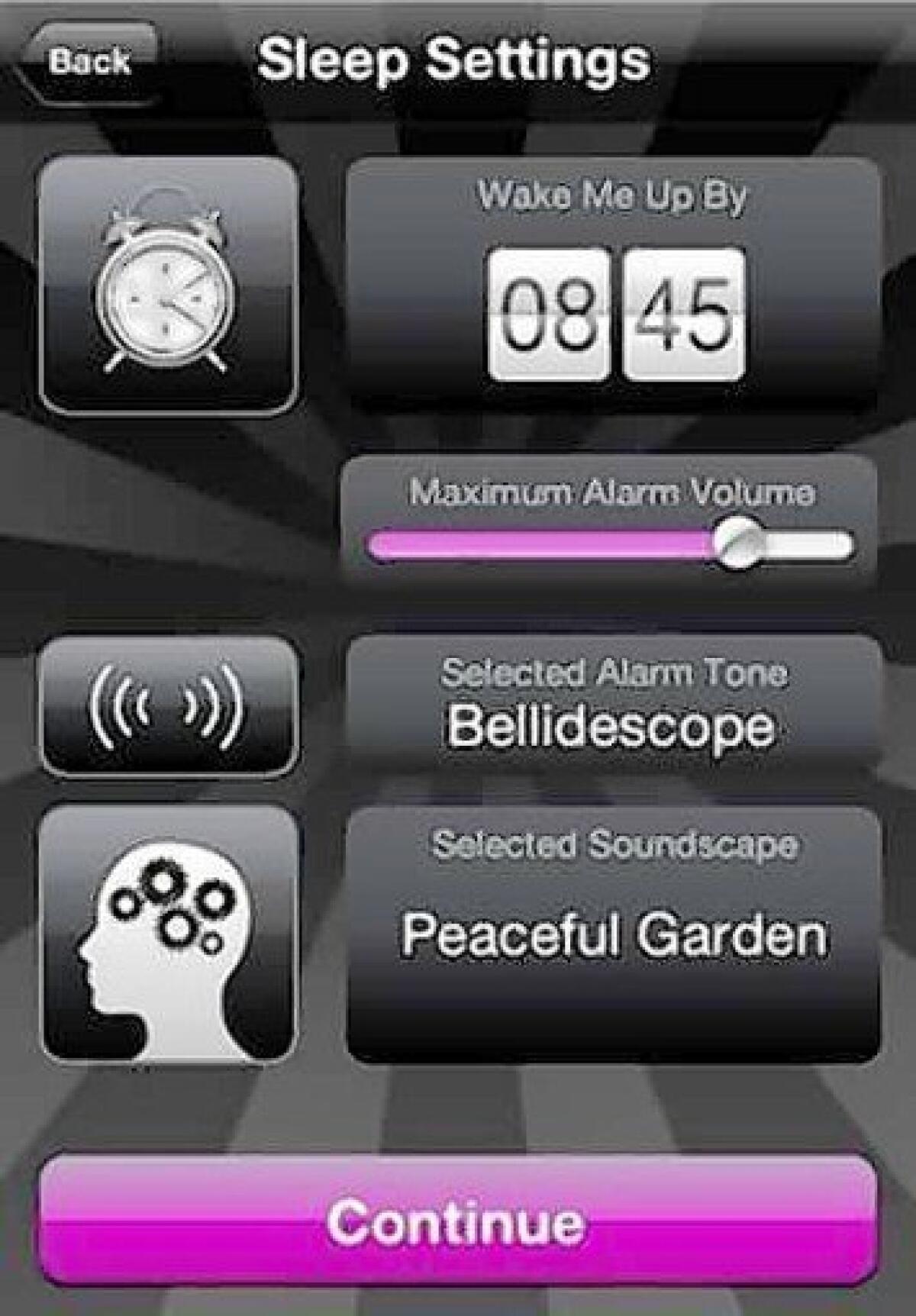

With Dream:On, you choose a dream from a menu of possibilities before you go to bed, and the app delivers that dream shortly before your alarm is set to go off.

But how? It’s all thanks to the motion detector in your iPhone (called an accelerometer). Because you move more in some stages of sleep than in others, Dream:On can use the motion detector to figure out what stage you’re in at any moment. In particular, you hardly move a muscle, except in your eyes, during the aptly named rapid eye movement stage. Dream:On is most concerned with this REM state, because it’s the stage in which you do most of your dreaming.

While the app keeps tabs on your sleep patterns all night, the time that really counts is the 20 minutes before your alarm is set to wake you. If Dream:On detects that you’re in REM sleep then, it immediately goes into dream-manufacturing mode. This means playing a “soundscape” — a cityscape, a naturescape, a trip-on-the-space-shuttle-scape — designed (no details are given about how) to induce your chosen dream.

Research suggests that this can work. “It’s well-known that people can incorporate environmental sounds into their dreams,” says Michelle Primeau, a fellow at Stanford University’s Sleep Center and a sleep physician at Stanford Hospital. Your phone rings: You dream that Stockholm is calling.

Primeau and other sleep scientists do have reservations about Dream:On. While motion detectors can monitor sleep patterns, Dream:On’s methodology is not ideal, and Dr. Douglas Prisco, director of sleep medicine at USC, calls its accuracy “iffy.” And environmental sounds don’t always waft you into dreamland. Sometimes your phone rings and you simply wake up. In which case, “hearing the soundscape could mean you get less sleep,” says Dr. Rafael Pelayo, an associate professor of psychiatry at Stanford’s Sleep Center. “And people are already sleep-deprived enough.”

Even the psychologist who dreamed up Dream:On, Richard Wiseman of the University of Hertfordshire in Britain, considers it an app in progress. He asks users to report their personal results for a “mass participation experiment” testing how well it works.

Of course, Primeau no doubt speaks for a host of scientists when she calls that “not exactly the best-designed study.”