NYC’s failed cap on sugary drinks prompts soul-searching

- Share via

After any military operation, participants huddle for what’s called a hot wash: an early after-action review that explores what went wrong -- or right-- in an effort to glean lessons for future operations. Public health officials are in the midst of just such a hot wash in the wake of a New York judge’s dismissal of a bid to ban the sale of colossal servings of sugary drinks at New York City eateries.

Justice Milton A. Tingling’s March 11 ruling, and the lessons that that setback holds for future public health initiatives, was studied in the New England Journal of Medicine on Thursday, in two Perspectives released online-early.

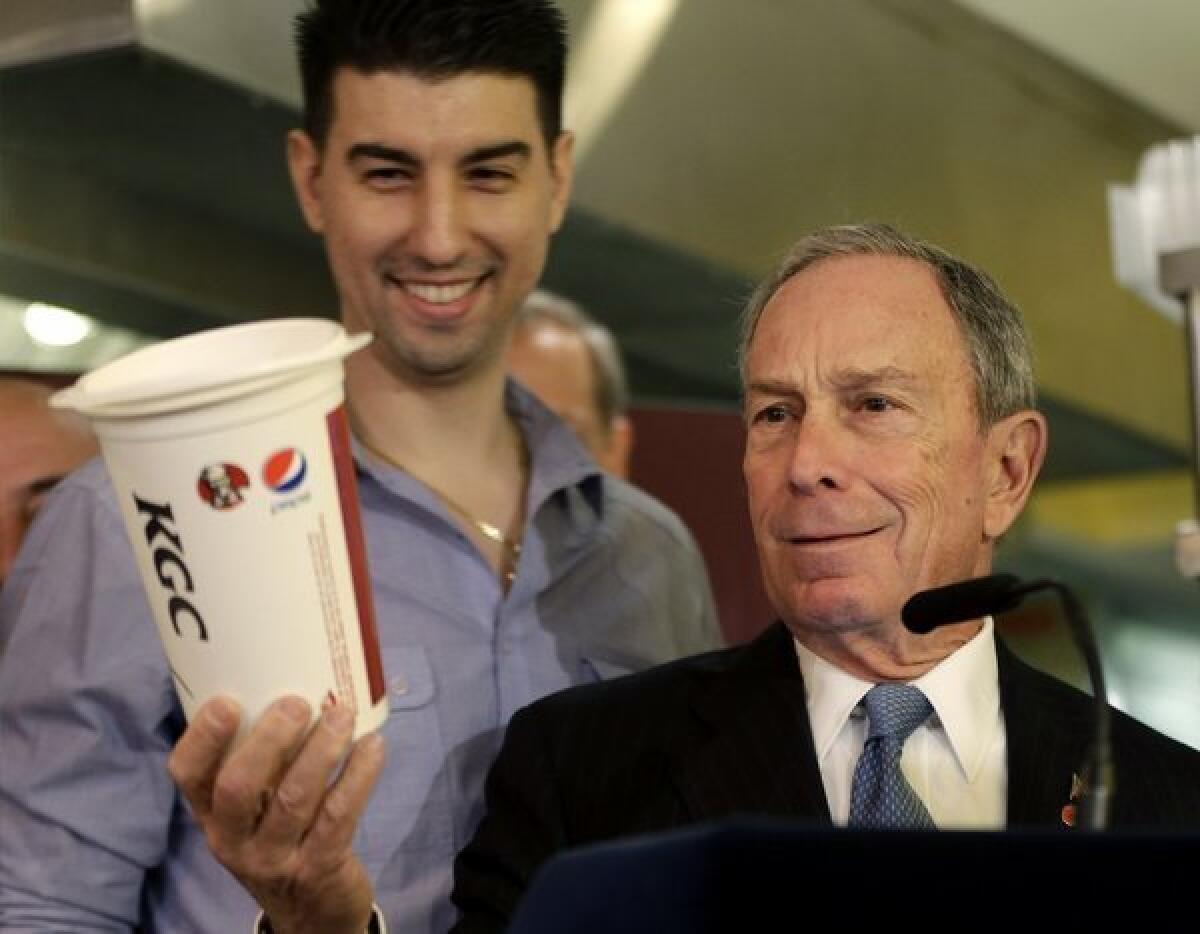

Their conclusion: The objectives and strategy may have been sound -- sugary beverages contribute to obesity, and reducing obesity likely will require reduced consumption of them. But the tactics that New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his allies used -- to forbid the sale of those drinks in large containers in some but not all establishments -- was flawed.

In one of two editorials published Thursday, a pair of Boston University bioethicist-lawyers dissect the ruling and conclude that Bloomberg and his public health department overreached and have invited a public backlash that will make future efforts to address obesity more difficult.

In a second editorial, a public health historian from Columbia University casts the proposed ban in the larger sweep of public health battles fought through the years and those to come. She suggests that if they are to combat diseases linked to obesity effectively, public health officials will have to return to their historical roots and attack the broad social and environmental conditions that allow disease and pestilence to flourish.

The two perspectives reflect an intensive soul-searching among public health officials in the wake of the failed New York City initiative, which most supported, at least in its aim. Shortly after Bloomberg floated his initiative, the American Medical Assn. abandoned its long-held neutrality on the subject of soda and acknowledged that taxing sugary drinks could be a useful tool in the fight against obesity. The American Public Health Assn. adopted a stronger stance in support of soda taxes roughly a month after the New York City Board of Health approved Mayor Bloomberg’s proposal.

In defending those policy shifts, physicians and public health officials cited a long list of studies documenting the role of sugary beverage consumption in fueling the nation’s obesity crisis.

Bloomberg’s proposal to block the sale of sweetened sodas in containers bigger than 18 ounces may have been full of exceptions and loopholes, writes Columbia University public health professor Amy L. Fairchild. But “the target is corporate behavior.” And picking such a fight, Fairchild suggests, might be seen “in the grand tradition of public health activism” in which public health officials refrain from blaming the individual for his wretched state and take on the larger forces -- whether they are poverty or corporate profits -- that predispose entire populations to illness.

“If we can challenge the industries and businesses that profit by promoting bloated serving sizes, perhaps we can take on other corporate enterprises that similarly contaminate our social environment,” Fairchild writes.

Wendy K. Mariner and George J. Annas, both attorneys and bioethicists, agree that laying blame on individuals -- “current proposals to shame people who are overweight” -- are “simply wrong.” But seizing on a tactic that invited the courts and public to cast health officials as paternalistic, overreaching and ineffective to boot was a mistake, they write. Legislatures are on firmer legal footing to take steps that limit access to sugary beverages, they assert. And levying a tax on sodas -- if tobacco is any guide, a more proven way to reduce consumption -- is a “reasonable alternative” to portion bans, they added.

In the end, Mariner and Annas write, “large corporations continue to use their influence and money to derail public health measures that could reduce their profits,” and public health officials have a war on their hands.

Essentially, the authors write, they won’t win it by picking the wrong battles.

“Agencies that overstep their bounds or adopt rules that are intrusive or just plain silly invite backlash, which can make effective public health regulation impossible. They make fools of themselves and heroes of the opponents of public health.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.