With homeless people as an audience, federal judge brings L.A. officials to skid row

- Share via

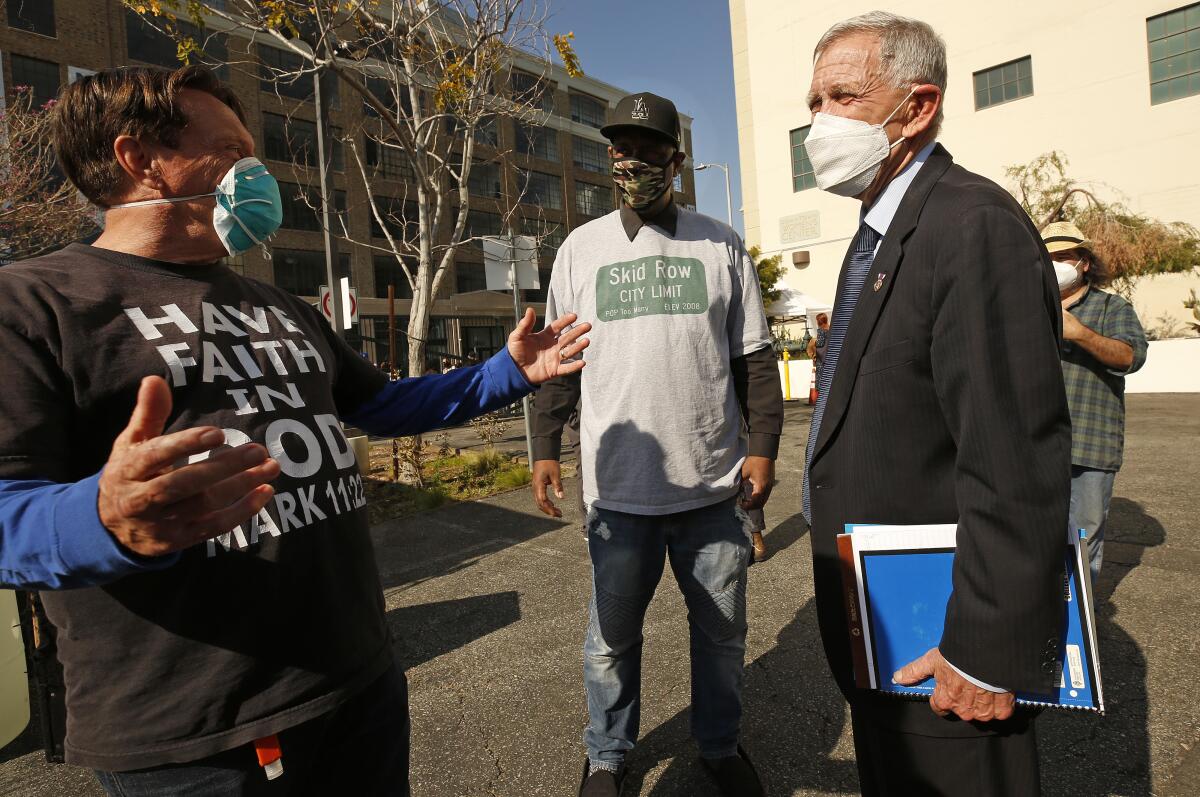

“This is not what I call a sound bite day,” U.S. District Judge David O. Carter observed Thursday as elected officials shuffled in and out of a tent better equipped for a wedding than a federal court hearing.

And yet here they were, at the heart of L.A.’s skid row, nearly a year into a court case seeking relief for homeless people in Los Angeles. Some offered specific remedies they’d like to see to help solve an ever-worsening homelessness crisis, while others spoke of the need for more collaboration and coordination.

For the record:

10:01 a.m. Feb. 5, 2021An earlier version of this article identified the city’s deputy mayor for homelessness as Jose “Che” Garcia. His surname is Ramirez.

Carter had called the plaintiffs, intervenors and defendants in the case here after spending much of Friday and Saturday —drenched — trying to get homeless women into tents that would shield them from the rain.

For a variety of reasons, that effort failed.

During the hearing, Carter — clearly frustrated by his inability to compel rapid change — fixated on this failure as endemic of something broader.

Over much of the past year, the judge has shown up at homeless encampments with tents and an entourage at all times of day. Here in his ad-hoc court, Carter laid out a broad course of action of where he’d like to see the case go.

At 76, Judge David Carter knows he shouldn’t be on skid row exposing himself to the coronavirus. But he wants more for L.A.’s homeless people.

A crowd assembled outside the locked gate to the parking lot of the Downtown Women’s Center, where the unusual hearing was held, listening intently to the proceedings over loudspeakers that competed with a mix of rap and Latin music playing on the street.

The case grew out of a lawsuit that was filed last year, just as the COVID-19 pandemic began, by business owners and residents who banded together to form a group called the LA Alliance for Human Rights. It demands an end to what it maintains are unsafe and inhumane conditions in homeless encampments — especially during the pandemic.

Reading from his own court documents at the hearing, Carter talked of a “long period of inaction by local government officials” after the Supreme Court struck down school desegregation in its landmark 1954 ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education. It took robust efforts by federal authorities and the courts before the ruling could be enforced. Carter openly wondered if Los Angeles’ homelessness crisis warranted similar, far-reaching action from the federal bench.

He asked that by Feb. 16, the city tell him what he could do if politicians fail to use their powers to get people — the majority of them Black and Latino — off the streets.

In the tent, these statements were met with a range of reactions from public officials, including City Councilmembers Kevin de León and Mike Bonin, City Atty. Mike Feuer and Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors Chair Hilda Solis. Most said that they’d prefer to see elected officials and not a judge supervise the response to the crisis.

Bonin offered the clearest vision of what he’d like to see. He wants the plaintiffs in the case, along with the city and county, to enter into a consent decree that Carter would supervise. The judge would oversee progress toward clear goals agreed to by all the parties.

“Our system is just not fundamentally designed to address the crisis that we were in,” said Bonin. “It is urgently important for the court to assume the maximum role that it can.”

Others, including Feuer, weren’t as enthusiastic about the prospect of intervention by the federal court. After Solis said she’d prefer the city and county to stay in control, Carter said that what he’s considering is much more far-reaching than just supervising an agreement.

“What we’re exploring now is far different than that,” he said.

What he’s trying to think through is what he should do if local officials fail to act or come to a consensus.

A notable absence was Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who said Wednesday night he couldn’t attend but had been in contact with Carter. The two text regularly, and met Tuesday to discuss the case. Garcetti’s deputy chief of staff, Matt Szabo, along with Jose “Che” Ramirez, the deputy mayor for homelessness, were present but struggled at points to answer questions from Carter.

During his nightly news conference Wednesday, Garcetti said that Carter didn’t have the authority to order sweeping changes in city policy “at this point.”

Offering few details, he said he’d instructed city staff to try to expand Project Roomkey, a program that rents hotel rooms for homeless people. This came after the Federal Emergency Management Agency announced that it would now be reimbursing all dollars that have been spent on rooms since the start of pandemic.

A judge is pushing the city and county of Los Angeles to clear homeless camps near freeways, but vacated an order requiring the clearance.

The number of beds available through Project Roomkey has decreased in recent months, and Carter and others said the dearth of available options for people in crisis on the streets was on display during the rainy weather last week. Carter, who had spent much of the spring focused on people living near freeways, now seemed preoccupied by the disproportionate number of people of color and women who are on the city’s streets.

Few attendees who spoke at the hearing fit that demographic until Pete White of the Los Angeles Community Action Network pulled out his phone and put his colleague Monique Noel on speakerphone. She gave an impassioned speech describing how the needs and views of Black women had been neglected for far too long.

At one point, White asked her to slow down because the “court reporter’s fingers are about to fall off.”

“There are thousands of women on skid row.... Emergency housing has not been made available to them,” Noel said through a crackling speaker amid cheers from the streets.

As he tours encampments around the region, Carter often takes photos on his iPhone. He had some of these images enlarged on posterboard for the hearing. They showed women — some poorly clothed, some shivering and some trying to set up tents — whom he met in the rain last week.

“We’re hearing [about this] in court and not seeing and feeling this,” Carter said. “I think it’s dehumanizing to not to show the faces of real people.”

One of the women he was referring to sat on a curb outside the hearing, listening. Michelle Coulter, 51, struggles to walk on legs wracked by arthritis. She normally sleeps in a tent outside the Downtown Women’s Center and has been on skid row since 2013.

Last week, Carter, De León and other officials met her as it poured rain and tried to get her help. Hotel rooms supplied by the Los Angeles Services Authority fell through, and the Downtown Women’s Center was unable to transition its parking lot into a place for people like her to get out of the rain.

With the help of a pastor who works closely with Carter, Coulter got into a nearby hotel for a night. It was a tiny salvation.

“It was a relief. I took a bath and I looked at myself in the mirror,” she said. “When I got to that room it made me want to do better for myself.”

After that night, Coulter returned to the streets and after the hearing finished, the pastor was trying to get her into a Project Roomkey hotel in Whittier.

Hours later she had arrived and would have a bed for the night.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.