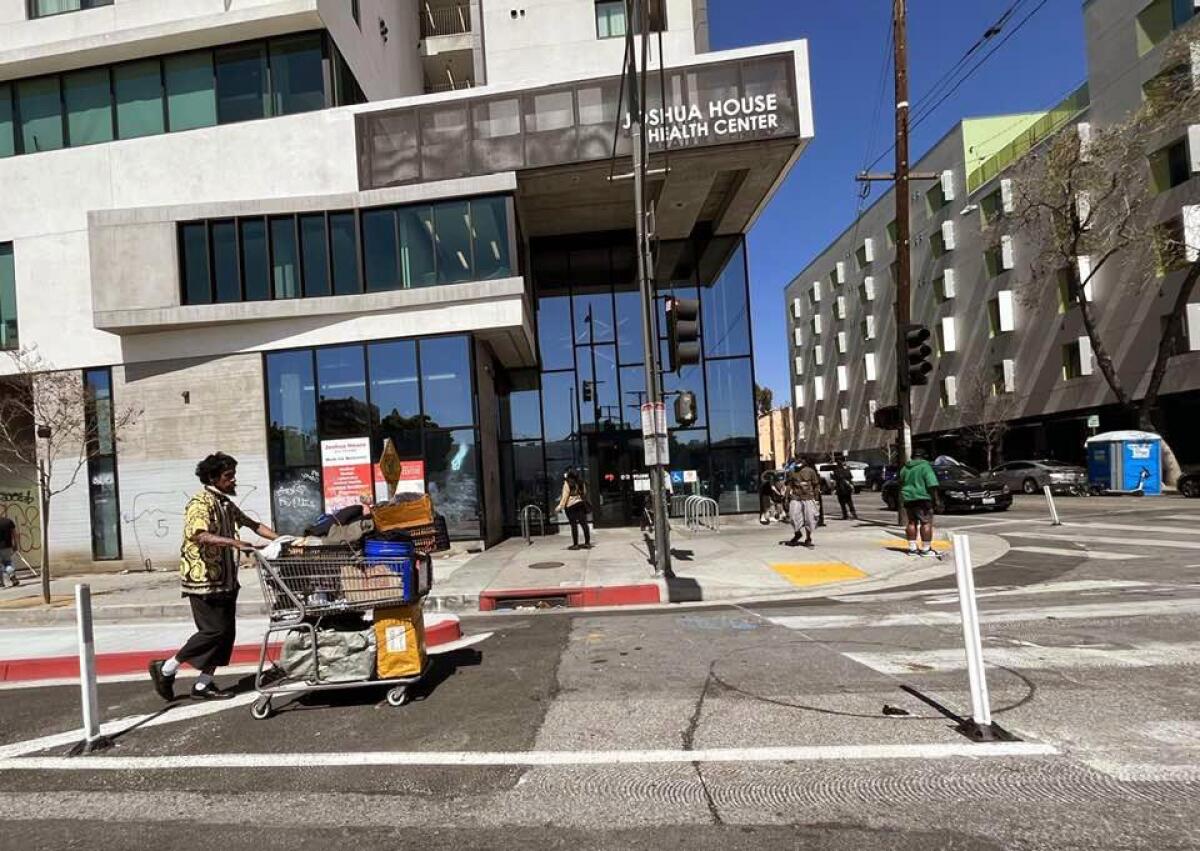

Skid Row receivership in danger of financial collapse, leaving 1,500 tenants at risk

- Share via

The receivership overseeing the welfare of 1,500 tenants in Skid Row is verging on insolvency, unable to borrow money and piling up $1.7 million in unpaid bills.

The financial circumstances have become so dire that Mark Adams, the receiver in charge of 29 properties owned by Skid Row Housing Trust, is asking for emergency action from a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge, or else he said he’ll have to cancel security contracts, lay off his staff and surrender the effort.

“The receivership is quite literally starving for cash,” Adams wrote in a court filing Friday.

To rescue the receivership, Adams suggested in the filing, the court itself would have to guarantee loans to operate and rehabilitate the buildings.

“The receiver asks the court to reassure potential lenders that the court is standing behind its receiver, that it is the credibility of the court that they have lent and will lend against,” Adams wrote to Judge Mitchell Beckloff in the filing.

Adams’ request is expected to be heard at a June 15 court hearing. Should the receivership collapse, it would be another devastating setback to the provision of homeless housing in Los Angeles, and especially for residents in trust properties, many of whom are elderly, disabled or suffering from mental health and drug problems.

Tenants at Skid Row Housing Trust buildings were issued eviction notices that the city attorney’s office deemed illegal. The receiver overseeing the properties has rescinded them.

Adams was appointed two months ago after years of mismanagement and financial disarray had left the trust unable to pay its bills. The nonprofit housing provider — the largest in Skid Row — had slashed staffing and maintenance, leaving the buildings in squalid conditions.

In response, Mayor Karen Bass and City Atty. Hydee Feldstein-Soto pushed to put Adams in charge of the trust’s portfolio of century-old residential hotels and newer permanent supportive housing complexes. Nearly 900 units were vacant, deemed uninhabitable or left in such shoddy conditions that public agencies refused to pay rent even though tenants were still living in them.

The court appointment gave Adams the authority to finance for repairs and upgrades, and once stabilized, to turn the properties over to other affordable housing providers.

Adams has since received approval from Beckloff to borrow $5.3 million — the amount he estimated was needed to finance operations through July.

But Adams has been able to secure only $1.8 million, leaving a cash crunch threatening the receivership’s existence.

In court documents, Adams provides a litany of reasons for the failures, including a lack of support and funding from city leaders, potential lenders needing assurances they’ll be repaid, and costs that are spiraling far beyond initial projections.

“The demands placed on the receiver, as it relates to the minimal funding available to address 29 properties, and over 2,000 units (some of which have active tenancies with individuals that are entitled to government benefits and other protections), is verging on the inconceivable,” Adams wrote in the filing.

Mark Adams is overseeing the welfare of 1,500 tenants in Skid Row. In prior cases involving Adams, tenants faced the risk of eviction and property owners lost their houses.

Neither Adams nor anyone else has produced an estimate for the full cost to rehabilitate the buildings while continuing to operate them — and where the money to do so will come from.

Normally, receiverships pay for repairs and the receiver’s fees by tapping properties’ equity or through proceeds from a property sale or increased rents. But the trust is on the brink of insolvency, federal and local restrictions prevent tenants’ rents from ballooning, and city leaders are desperate to preserve thousands of apartments for formerly homeless residents. City housing officials have acknowledged the city treasury probably will be on the hook for at least some of the price tag.

Costs are swamping some of Adams’ initial estimates. Adams had to revise his projections to account for $1.3 million in security for the 29 properties in May alone — more than double his first forecast. Adams said that more personnel were needed to stand guard while urgent fire and physical safety repairs were made to the buildings.

Similarly, the price tag for rehabilitating the buildings is proving unrealistic. Adams told the court in May he hoped to spend an average of $3,000 a piece to fix nearly 400 units where the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles has stopped paying vouchers that cover much of tenants’ rents.

But in his June 9 filing, Adams said that roof repairs at one property, the Rainbow Apartments, are needed before resolving problems in top-floor units, and that three other units at the complex were destroyed, necessitating more work than anticipated. Adams estimated the cost to make these repairs at $270,000, an amount not yet in the budget.

“Therefore, the work cannot be done despite the demands,” he wrote.

Without the repairs, the housing authority will continue to withhold rent money, further squeezing the receivership’s finances.

City officials are pressing Adams for more detailed accounting of his tasks, saying that the receiver left out of his April financial report expenses for janitorial services, costs for his outside attorneys and his own fees.

“The city understands that the first month of the receivership was a time of transition, especially for such a large portfolio,” Deputy City Atty. Alia Haddad wrote in a filing Monday. “At the same time, the nature and complexity of the receivership’s work makes it all the more critical that accounting be accurate, timely, and complete.”

Haddad’s filing did not address the receivership’s overall financial problems, and Feldstein-Soto did not respond to a list of questions from The Times.

Adams told The Times that as of Tuesday the receivership had $336,000 left in its bank account, with $1.7 million in outstanding obligations.

One debtor is JRM Private Security, which provided guards for 11 of the trust’s properties through May. John McKillop, the firm’s president, said he canceled the contract after he wasn’t paid for weeks, leaving with an unpaid balance of $910,000.

In preparation for the work, McKillop said, JRM hired more than 30 guards and purchased two patrol cars, and, because Adams was a new client, included a provision in the deal that the bill would be paid weekly.

The firm began work April 18, and McKillop said that Adams paid $250,000 for the first week, but that it has received nothing since.

“It all went sour the minute we said, ‘Can we get paid?’” McKillop said.

In response to questions from The Times, Adams said that he terminated JRM after questioning the firm’s performance and that he’s planning to ask the judge for how to proceed with its debt.

Adams is one of the most experienced receivers in the state, handling 300 such cases over more than two decades. But concerns over his selection for the job have been simmering since The Times reported in May that in some of his prior cases tenants faced the risk of eviction and property owners lost their houses, while multiple judges determined he inflated his fees by six-figure amounts.

Feldstein-Soto has told The Times that Adams was uniquely qualified for the role and needed to be installed urgently because of the trust’s collapse. But she said the city did not formally vet his resume before recommending his appointment.

The judge’s ruling comes two days after three people died of drug overdoses in an apartment unit at a Skid Row Housing Trust building, 649 Lofts.

Last week, Feldstein-Soto, Bass and other city officials blasted Adams after the property management firm he hired sent eviction notices to 451 tenants behind on rent. Feldstein-Soto said the notices were illegal under city law and violated a promise Adams had made not to evict residents solely for nonpayment.

Adams said that the eviction notices were sent without his knowledge and that he sent letters rescinding them once he became aware.

Adams said the perceived lack of support from city officials is harming his ability to raise money.

The city has been negotiating with investors representing a half-dozen of the trust’s more financially stable properties to remove the buildings from the receivership and put them under the control of local nonprofits.

The potential exit of some of the trust’s highest-value assets has spooked potential financiers, Adams said in his filing, with the possibility of diminished collateral forcing them to demand higher interest rates.

Loans to finance receiverships, which involve troubled properties in need of substantial upgrades, typically include high rates to entice lenders who fear they won’t get their money back. After the city officials learned last month that Adams had taken out a $1.3-million loan at a 15% interest rate, they asked for prior court approval anytime a loan’s interest rate would exceed 10%.

Adams told Beckloff that no outside lender will agree to those terms, and neither the city nor any of the existing investors in the trust’s properties, which include U.S. Bank and Wells Fargo among other prominent banks, have stepped up to provide cash in the meantime.

“These are some of the major financial institutions in the United States, as well as the city of Los Angeles, and with all of these resources, there was no movement,” Adams wrote in his filing. “The silence/lack of response speaks volumes.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.