A brush with the bold

- Share via

Pack it up, beige and white. You’re no longer safe. Color has blasted its way back. Paint makers are pouring Pink Minx, Mystical Grape and Relish Green into gallon cans. Shocking colors are being slathered on walls by TV-show decorators who see it as a quick, inexpensive way to make over a room, and rich hues have invaded once-sterile furniture showrooms, stirring the need for Tang-colored bookshelves and banana sofas.

Inspired by all they see, savvy homeowners have also seized the color wheel. Those in traditional houses are rolling over plain-vanilla walls with blueberry latex and re-covering khaki chairs with multihued beaded silks. Others in sleek glass-and-steel moderns are injecting prismatic colors that are straight from Fisher-Price toys.

These people are not timid. They understand the power of color, that it can update a room, create a space that’s welcoming, highlight an architectural detail and camouflage a flaw.

But color is more than visual fizz. It changes us. Robin’s-egg blue is calming, while neon orange makes us edgy.

Color, too, changes. It is influenced by light, climate and its immediate surroundings. That’s why Chinese red, Mexican pink, Indian saffron and Southwest terra cotta often look best in their birthplaces.

Complicating everything for those of us who think gray is a bold step is the fact that no one sees color the same way. Your red-orangy Coca-Cola red may look like someone else’s stoplight red.

And the names: Vanishing Point and Cumulous? Can’t we just say white?

No. It’s a world filled with Apricot Butter, Mistletoe, Mushroomy Elephant. And those of us not fluent in the language have to learn it.

But we hesitate. We worry about burning up our money, time and pride only to be forced to live in something that doesn’t reflect our tasteful selves. Color-visualization tools are no help. We hold up a Lilliputian fabric swatch and see mostly our big thumb. Paint color chips are so tiny they seem rescued from the bottom of a kaleidoscope. And they don’t even match the color in the can.

As one interior designer lamented about some of his clients, “Being a colorist is like being a therapist. Your clients don’t know what the problem is, but you have to tell them how to solve it.”

Here it is, then, the first truism for getting color to work for you: You can sit through home improvement seminars until your legs go numb. Read the flood of decorating books and magazines until your eyes clamp down. Looky-loo your way through every model home on the market. But you will get it right only by trying. And failing. And trying again.

Find comfort in this: Even the pros, who know the color families better than their own, mess up. But they keep adding and subtracting until everything balances out — lights and darks, hards and softs.

There are different ways to do this. Carl Tillmanns is a house-painting contractor and color designer who has hued up Tom Hanks’ beach cottage, Barbra Streisand’s storybook-style estate and Jerry Seinfeld’s ultramodern mountain retreat. Tillmanns likes color and pours it on walls with a skilled eye and hand.

Jeffrey Alan Marks, on the other hand, is an interior designer who dispenses color as if through an eyedropper. He’ll design a monochromatic room and add a jolt of color such as a canary-yellow chair.

Both live in graceful Los Angeles homes enhanced by their choices.

Tillmanns’ Mission-style two-story near Farmers Market is his lab. “I learn through time, experience and trial and error,” he says. “Each room is a process. You build on it.”

When he and his wife, TV director and screenwriter Rachel Feldman, and their two children, Nora and Leon, moved into their house eight years ago, they didn’t want furniture or artwork to have visual punch. Instead, the walls became the focus.

Slowly, layer by layer, Tillmanns found the way to make the once-neglected rooms grand with a montage of colors and faux finishes. Cheesecloth-applied glaze added texture and depth, and he put brown and purple deck paint on the resin entry floor and stair risers to simulate tile.

In other rooms, Tillmanns pulled up the orange shag carpet to reveal oak floors. Planks in the dining room lay on a diagonal, a geometry that inspired him to create a diamond pattern on the walls using a dozen colors from the other rooms’ leftover paints. The soffit ceiling is a confetti of bronze, copper and gold leaf.

The large living room has been visually divided into an office, sitting and music areas. Tillmanns wanted the sitting area to be the highlight of the room, so he painted the fireplace surround and mantel the same colors as the velour sofa — cerise and black.

The walls, as in other rooms, are in versions of muted yellow ochre. “Depending on the time of day, the house glows yellow, golden, green and even red,” Feldman says.

Their daughter, Nora, asked that her bedroom on the second floor be painted a potentially clashing combination of pea green, cranberry and purple. Separating the colors into defined spaces seemed the best approach. Tillmanns rolled the walls and coved ceilings with pea green, then applied cranberry on top in the shape of huge TV screens. Purple is used as an accent color.

“There is a lot of color in this room, but it doesn’t shout,” says Tillmanns, who often adds powdered paint pigments to customize store-bought paints. “Using bold color doesn’t have to be scary. We think this is one of the most comfortable rooms in the house, even though it may be the loudest.”

Leon’s bedroom is muted aqua with gold, green and cornflower-blue accents included in a hand-cut stencil surrounding the room.

In the master bedroom, there are six intensities of green, graduating from dark green above the baseboards, where busy feet roam, to pale green on the ceiling, where sleepy eyes take in their last view of the day.

Tillmanns was a dancer and choreographer in his pre-paintbrush career. He has two master’s degrees in fine arts, one in dance from Sarah Lawrence College and one in musical theater from New York University. He uses his background to direct the eye and let the space tell a story. “I’m a color director,” he says.

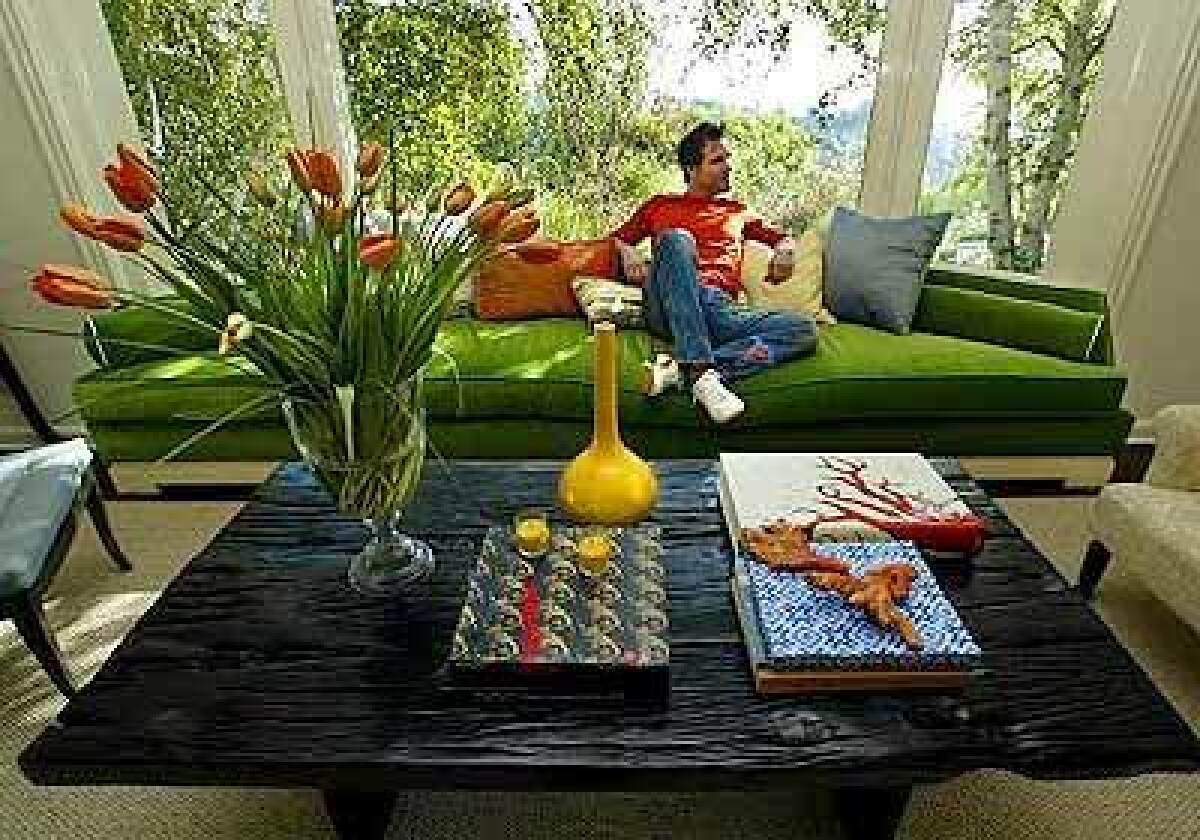

Designer Marks could be called a color dramatist. He uses it sparingly, as punctuation. His rooms, painted in a parchment color, are made bold by pillows, art and flowers.

Marks moved into his Hollywood Regency home in West Hollywood two years ago. It was built in 1938 by architect and set designer Leland Fuller, who used aspects of Georgian, Federal and Second Empire revival styles with a bit of Streamline Moderne. Later, John Woolf, who designed homes for George and Ira Gershwin and Cary Grant, added on to the two-story house. “It’s theatrical,” says Marks, making it “a perfect base for strong colors prevalent in the 1930s.”

Its previous owner had decorated it in an ‘80s bachelor-pad motif with dark curtains and gray walls. Marks — who graduated from the Inchbald School of Design in London, where he learned that color can break through gloomy days — replaced the dreariness with rusty suedes, quilted orange and apple-green silks, and shiny yellow-glazed cottons. The runner on the stairs has thin stripes of these colors, which are also echoed in his collection of antique Chinese porcelain jars and vases.

“Everyone has seen beige and what it can do,” he says. “But it’s not stimulating. People don’t want their house to look like their neighbors’ or to look store-bought in that monochromatic, no-feeling manner. They want the emotional charge that color gives.

“It is the easiest way to get a reaction,” he adds. “When I was in college I had a shocking pink bedroom. How do you think that went over on fraternity row?”