Look homeward, angels

- Share via

One scene in particular haunts the memory.

A woman, dead by her own hand, is lifted from a bathtub by her lover. The eye focuses not on the floor where the man so tenderly, sensually places the body of his beloved as though she still breathes, but moves away, upward, toward a holy light. Toward a huge and magnificent square of stained glass that gives pause and thereafter breaks all concentration on the movie’s action. What a great idea, is what comes to mind. A cathedral-like window in a hip loft bathroom. And where did they get that fabulous tub?

Maybe that’s not the reaction Patricia Louisianna Knop and Zalman King anticipated when they wrote and produced the 1992 pilot for “Red Shoe Diaries,” the erotic Showtime series. On the other hand, they would be the first to appreciate the distraction. They’ve been hypnotized by the magic and mystery of households since they hooked up 40 years ago.

It can’t be denied that certain expectations are inevitable when given the chance to visit the Knop-King residence, however juvenile they may be. After all, the couple has collaborated on some of moviedom’s steamiest: “Two-Moon Junction,” “Wild Orchid,” “9 1/2Weeks.” So amazement is total upon entering the front door of their house in Santa Monica: A host of angels is there to greet the visitor.

They look to the heavens, they look on your face, they watch you, follow you, pray for you with their graceful hands and they are utterly, breathtakingly luminous. “I never feel alone here,” says Knop, who has her own kind of radiance -- shining hair, eyes moist with good will, voice creamy and calming. “I always have a sense of being protected by them. They have compassion and hope, a beautiful energy.”

No matter that many of them are hundreds of years old, from Colonial Mexico, and all of them inanimate. Knop speaks of them as if they were living entities, part of the family, telling of their pleasure or displeasure with their spot in a room, and it’s hard not to see them that way yourself. Especially when she so poignantly relates their sad tales, how they were castoffs, no longer valued, just old, used up things hauled out of churches and dumped or left to waste away in attics and basements; two were pulled out of a fire.

“This is a shelter for endangered angels,” says Knop. “A sort of halfway house until they can go back home. They really will travel on, probably back to churches, at a safer time. The right time, the right place.”

The whole crazy beauty of Knop and King’s house is that it is an ingeniously devised refuge for all manner of the discarded and unwanted. Ever since the couple arrived in Los Angeles in the mid-1960s, poor and struggling, they have furnished their dwellings with salvaged items. King was just beginning his career as an actor and Knop as a painter and sculptor. It took them awhile to establish themselves in their careers, but only one week to pull together their $65-a-month apartment. They found a whole roomful of Victorian wicker that had been thrown in a garbage bin, and so they carted it to their little pad in their $25 Studebaker.

“L.A. was an absolute treasure hunt,” remembers Knop. “People were throwing away incredible things, you can’t imagine. We had a beautiful place even then.”

Several years went by before they could afford to pay more than flea market prices for things, but by then, there was no going back. Nothing would do but to make everything a treasure hunt.

“I still have that same scrounging sensibility -- believe me, “ says Knop. “Going to a gallery or store for something that’s already been discovered ... we don’t think that way. What I’m looking for is the treasure I’ve never seen before -- and in my case, it’s usually big. That’s the force that propels me through my one-millionth flea market.”

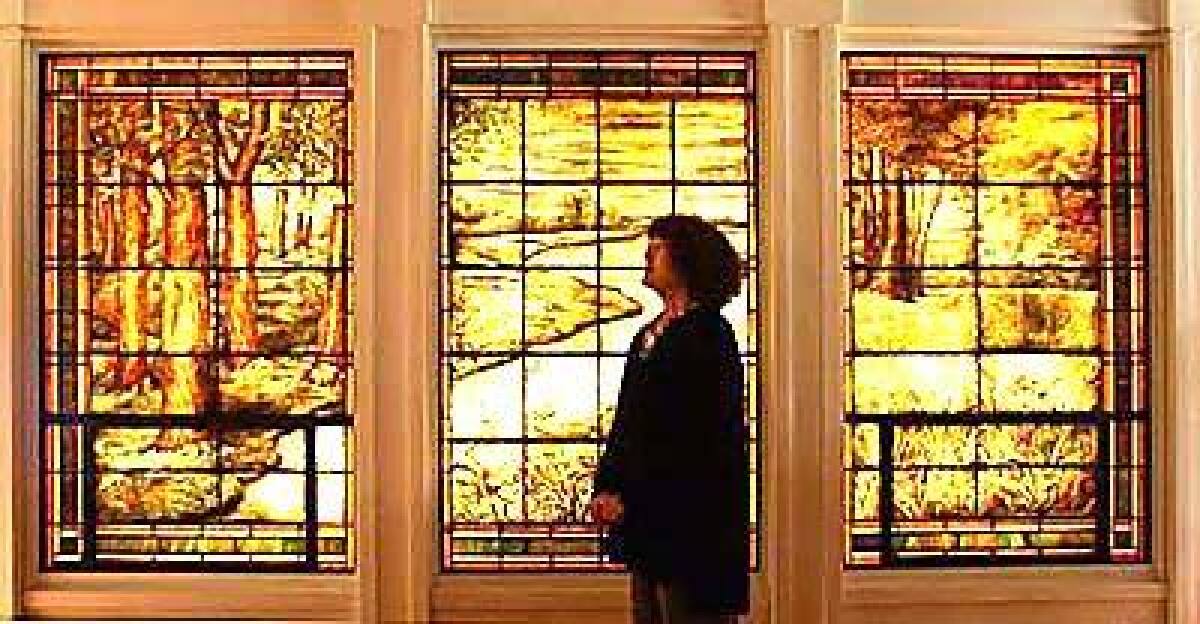

Even their garden is a found object, of a sort: After the Northridge earthquake in 1994, they salvaged tons of dirt, bushes and bricks from destroyed properties. They paid $600 for 3,000 tiles off the façade of a Victorian building in London, and tiled their bathrooms, stairs, dining table, outdoor tables, side tables and the fireplace surround with them. For $1,500, Knop got three massive, soot-caked windows from a Greene & Greene demolition back in the early 1970s. The next day she and her husband took sledge hammers and began knocking out a wall to install them. At the Rose Bowl flea market, she paid $50 for a bag of Aubusson fragments, and thus Aubusson pillows line the oversize sofas and the opium bed that once belonged to Mary Astor, for which Knop traded a sculpture. From the store room of a Glendale drugstore she took home a valuable Meyer of Munich window.

Three decades ago, when Knop got the yen to make a sculpture of her life on a carousel -- her mother and father would be in a ticket booth, she would be reaching for the brass ring -- she went on the hunt with her two young daughters, Chloe and Gillian. “I said to the kids, ‘We’re gonna go find a carousel now.’ ” (Knop often refers to the magical way things come to her, “ the number of strange coincidences” just when she needs them.)

“Our car conked out on Venice Boulevard and I heard this ‘toot toot toot,’ ” she says. “Behind a little wall was a kiddie land. And there sits this wonderful carousel. I asked the owner if he wanted to sell, and he said absolutely not. So we got on a roller coaster and went up to the top and it paused just in time for me to see a tool shed down below. And in that tool shed was a paw sticking out.

“I went back to the man and said I’d pay him cash for whatever was in there. He said, ‘Come back tomorrow with $5,000 in a paper bag.’ Well, we didn’t have that kind of money. We were living in an $85-a-month apartment. That night the phone rang and it was Freddie Fields, who owned ICM, asking if I would sculpt two of his songwriter/singers, Johnny Hartford and Jennifer Warnes. I said, ‘Yes, but it will cost you $5,000. And I have to have it tonight in a paper bag.’ ”

Knop got an entire carousel, 54 animals in all, but ended up keeping only eight. They had to sell the rest to live.

Today their house -- the kind to which people generally affix the adjective “rambling” -- is a wildly individualistic wonderland of aesthetic recycling and a laboratory for the creative imaginings of two maverick visualists.

The whole atmosphere is one of heightened reality, almost a hallucinatory ether. Think this: Walt Disney, P.T. Barnum and David Lynch collaborating on a tale about an artist, a mystic, a magician, a romanticist, a sensualist, a pixie and a Victorian eccentric who are engaged to design a household and are set loose with all their unbridled raptures. That will take you inside the Knop-King interior. It is part cathedral, part fairy tale illustration, part museum, part fun house, part Hollywood set, part Jungian subconscious made boldly, baldly conscious.

If our fantasies are just a pastiche of memories and illusions about ourselves and the world, then one could argue that Knop and King have given their fantasies a material presence by creating an artistic and architectural pastiche. In effect, they have obliterated the emotional distinction between their work and their home.

They liberally use objects from their home in their movies, and bring objects from their movies to their home: The stained glass window in the bathroom scene is now in their kitchen.

“Our lifestyle, for better or for worse, is really manifested in my movies,” says King. “And vice versa.”

Theirs is an intensely personal, sensually driven house, reflecting psyches turned inside out, so much so that it’s bound to discomfit the inhibited.

Chloe King, a screenwriter, remembers going through a mix of emotions growing up surrounded by religious art, menagerie beasts and gargantuan sculptures of her mother’s friends.

“There was a period when everything was terrifying. Nothing could rationalize it, all those carousel animals. Then came the period when I just wished I lived in a Brady Bunch house. But when I was around 11 or 12, I paid more attention to people’s reactions when they walked in, and I started to think it was pretty cool. Having said that, after being around that kind of obsessiveness and passion all my life, I would be happiest living in a hotel.”

Those reactions, says her sister Gillian Lefkowitz, a painter and photographer, run along the lines of a gasp and sudden speechlessness, or a screaming exclamation of disbelief. “If anyone ever comes in and doesn’t react,” she says, “then I’ll know they’re the walking dead.”

In its own distinctive and modest way, the house is a manifestation of the same impulse that drove Julia Cameron’s designs for Hearst Castle -- assemblage. While the San Simeon estate was an assemblage of artifacts shipped from Europe, this is a highly decorative assemblage of found artifacts gathered from here and there. Assemblage is, in fact, the one distinguishing contemporary art form to come out of L.A., going back to Wallace Berman and George Herms.

It also is an underlying aesthetic in the film industry. Films are never imagined whole, but are rather, themselves, assembled from found artifacts. They recycle, in a new context, characters and events from actual life, from other art forms, from the fashion of the moment.

Like their films, Knop’s and King’s house says L.A. You wouldn’t find it anywhere else. “It takes some getting used to,” King admits. “We definitely march to our own drummer. Everything we do is both a curse and a blessing, I would say.”

Knop is planning her next artistic installment in the bedroom her late mother used when she visited. She took away a truckload of fragments from a Tony Duquette auction at Butterfield’s, and intends to go “really over the top” in the manner of the flamboyant Hollywood interior designer.

Most of their belongings, they each separately point out, are meant to reflect joy. “Everything in the house is about a sharing of pleasure and hope,” says Knop. “It’s a reaching for the light.”

She mentions the big bronze sculpture she made of her and her husband, inspired by lines from a Tennyson poem on a needlepoint pillow she used to keep by her desk.

The merged figures, which have a kind of abstracted realism, are ascending on wings created by their mutual support of each other.

Knop begins to recite, to the best of her recollection:

Take wings of glory and ascend

And in a moment show thy face

Where all the starry heavens of space

Are sharpened to a needle’s end.

“In a way that’s sort of the philosophy that permeates everything in the house. The whole winged thing,” she says. “Even the plants, which grow inordinately quickly, seem to be ascending in the same way. Wings of glory. Always reaching for the light.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.