The rumrunners? They got priced out

- Share via

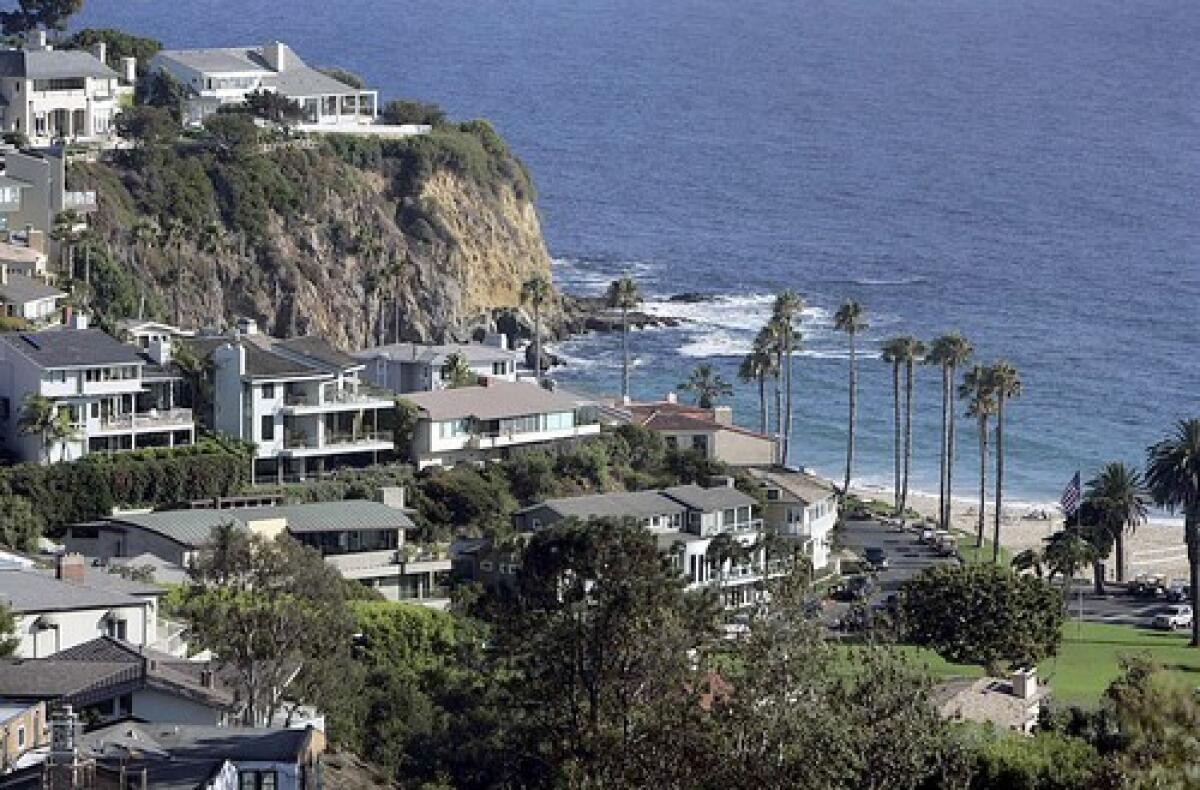

The private community of Emerald Bay, named for its clear, green waters, lies along the sunny stretch of Pacific Coast Highway between Laguna Beach and Corona del Mar. Once the site of modest vacation cottages, it now stretches, meticulous and pristine, behind white gates — its own little universe.

Beginnings

Emerald Bay’s past is charmingly rakish: In 1906, rancher James Irvine, eager to pay off his gambling debts, sold 148 acres of his land for $26,000. He had no way of knowing that his beachy soil eventually would be home to one of the most expensive private communities in Southern California.

The land changed hands, serving as a farm and then as a stop-off for rumrunners. In 1929, it was divided into smaller lots and sold off. Early purchasers built small, rustic summer homes on their lots. During World War II, when the cottages were rented out to the families of officers stationed at El Toro military base, Emerald Bay’s population became increasingly permanent.

After the war, with land values soaring, many of the beach cottages were replaced by larger, more luxurious houses. Today, the 500 or so houses are, for the most part, the primary residences of those fortunate enough to be able to afford them.

What it’s about

Privacy, luxury and autonomy would seem to be Emerald Bay’s keywords. The community manager, Toni Schmitt, is shy about talking to the press.

“There’s no reason for publicity,” she says, “and privacy is important.”

The community’s gates are operated by transponders, and security guards are stationed on each side of Emerald Bay’s private beach. Once inside, the living is enviable: The community association is meticulous about maintenance. Houses include small, older Craftsman styles and grand Mediterraneans, all extravagantly outfitted and maintained according to the architectural committee’s strict guidelines.

Insiders’ view

Despite its proximity to Emerald Canyon and Crystal Cove State Park, Emerald Bay has kept little of California’s natural wildness. The foliage is carefully manicured and more reminiscent of a polished country club than a laissez-faire beach community. Tennis courts, two swimming pools, a community center and a private park make up the common areas.

One of Emerald Bay’s shining glories is a half-mile stretch of soft-sanded beach protected from the elements — and outsiders — by rocks on each side. Those who have hillside homes zip through a private tunnel to the beach on golf carts, the community’s latest craze.

“We’ve turned into a golf-cart community without a golf course,” says Nancy Casebier, a Realtor and amateur Emerald Bay historian whose parents bought one of the empty lots in the 1940s.

“In fact,” she says, “a golf course is about the only thing we don’t have — besides a general store.”

The golf carts, Casebier says, have done a lot to bring the community closer together. “No one’s driving a Ferrari this way,” she says, “and it’s much more social because you’re waving at people and people are jumping on the back for a ride.”

Good news, bad news

This is a destination location. Residents buy their houses while in their 30s and 40s, raise kids and live out their lives here.

“The people who live here have been here for many generations,” says Emerald Bay resident and developer Nicholas Costa, who built two of the community’s houses. “They pass their homes on to their children.” Residents know and trust their neighbors, and community activities are widely attended, with holidays celebrated elaborately.

Even minor occasions are carried out with pizazz. For example, at a recent community dinner for the high school crosscountry team, the hosts offered carb-loading options for the kids and valet parking for parents.

Residents have proven more than just fair-weather friends. Eighty-nine Emerald Bay homes were destroyed or damaged in the 1993 Laguna Beach fire, and neighbors opened their doors to victims. “We’re an affluent community,” Casebier says, “but when you lose everything, you lose it. It brought people to their knees.”

On the market

Getting behind those gates is no mean feat. The least expensive house on the market right now is a three-bedroom, 2 1/2 bathroom house with 1,729 square feet on the hillside. It has a private patio and hardwood floors, but it lacks one of the neighborhood’s enviable ocean views. It’s listed at $3.2 million (oceanfront properties go for considerably more).

A loftier six-bedroom, five-bathroom, contemporary hillside house is on the market for $7.395 million. It has a generous 5,000 square feet, an ocean view and a courtyard and spa.

An ocean-side California bungalow-style house, which doesn’t have direct beach access but offers an unobstructed view and four bedrooms and three bathrooms in more than 2,740 feet, is listed at $15.2 million. Location, in this case, is everything.

Report card

Emerald Bay students attend schools in the Laguna Beach Unified School District. El Morro Elementary scored 868 out of 1,000 on the 2006 Academic Performance Index Growth Report. Thurston Middle School scored 839, and Laguna Beach High School, 821.

Sources: “A History of Emerald Bay, Stories and Recollections 1906-1956” by Nancy Casebier (self-published in 1999); https://www.inthebayrealty.com ; https://www.cde.ca.gov/ ; https://www.ebca.net .

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.