Pot luck along the road to Santa Fe

- Share via

SANTA FE, N.M. — The words astonished me when I read them:

“Pueblo people believe clay has life. Potters speak to it, pray to it, revere it.”

My wife, Sandy, and I have been modest collectors of Pueblo pottery for 14 years, and still I was surprised when I read those lines recently at a Pueblo exhibit at Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. Here was a spiritual explanation for a potter’s dedication. And maybe it explained why Pueblo pottery intrigues us.

From one polished black bowl, purchased on our first visit to Santa Fe in 1988, our collection has grown to 28 bowls, jars, pots, seed catchers and whimsical “storytellers,” an adult man or woman holding half a dozen youngsters in lap and arms. Pueblo pottery is a living presence in our household. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t pick up a piece, caressing it as I might a beloved pet. Can there be a better souvenir of a stay in New Mexico?

On a 10-day visit last month to Santa Fe and Taos, we went pottery hunting. As amateur collectors, we were not looking for the best workmanship or historic treasures; those pots cost thousands of dollars. Nor were we interested in the best price. We were looking for fun and cultural insights and for stories to tell of our shopping adventures. On this trip, we bought four pieces ranging from $40 to $310. Each appealed to us as the work of a skilled and dedicated potter.

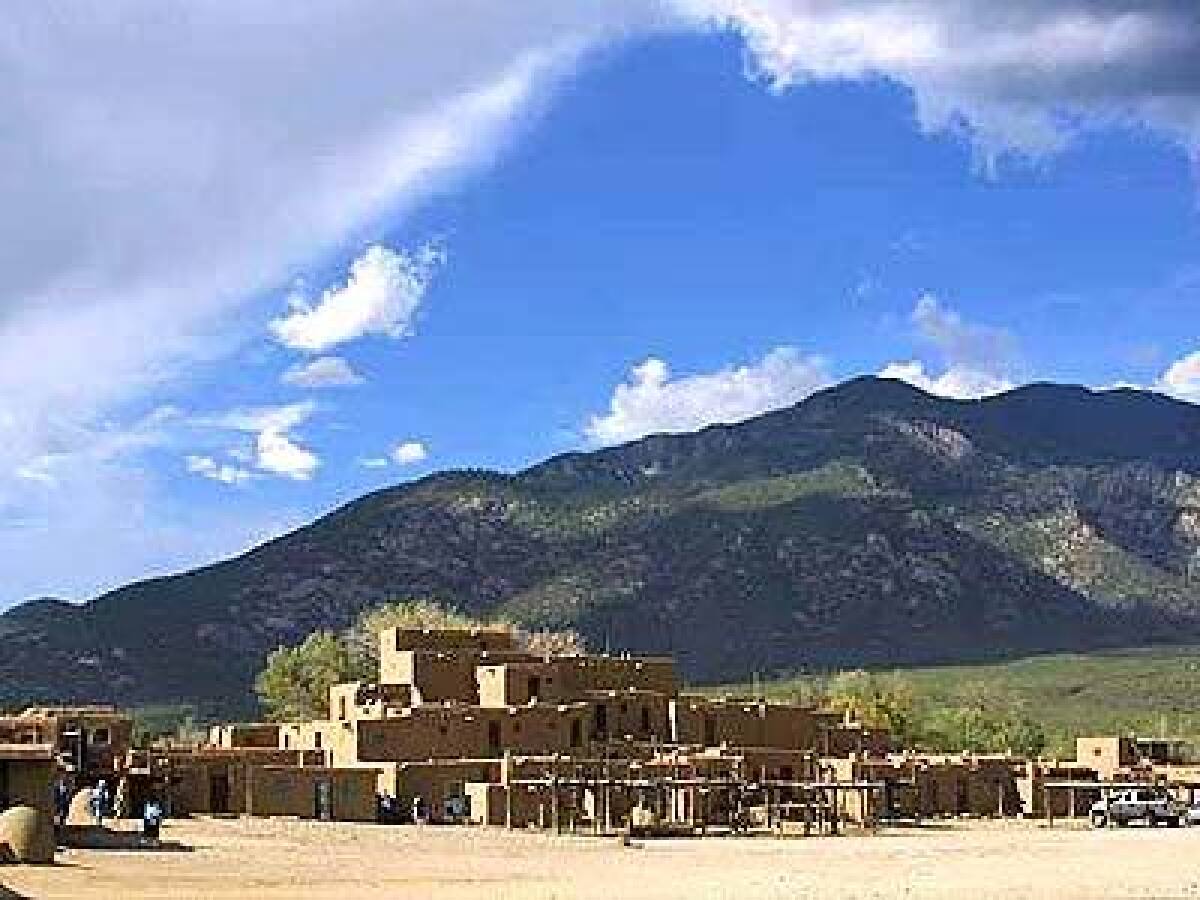

Our first excursion was to Taos Pueblo, about three miles north of the city of Taos. About 50 Pueblo Indians live in the two major adobe buildings, much as their ancestors did in 1540, when the Spanish conquistadors showed up. Now, as then, there is no electricity, no telephone, no plumbing. Water is carried by bucket from a lake-fed stream.

Taos Pueblo is the northernmost of New Mexico’s 19 pueblos, or reservations. Most are concentrated on or near the Rio Grande and are easy day trips from Santa Fe and Taos. All welcome visitors, although with varying degrees of hospitality. A fee is charged at some. At Taos it’s $10 per person, which includes a 20-minute escorted tour of the historic plaza.

The two main buildings on the plaza, the North House and the South House, are believed to date to about 1450, said our guide, a young tribal member named Tiffany. That would make them among the oldest residential structures in continuous use in North America. They resemble apartments stacked haphazardly five stories high, each story reached by a ladder from the terrace below. Their rounded edges and flat roofs have come to characterize Southwestern architecture. Santa Fe, the beautiful old state capital, looks like one vast pueblo.

It was in the South House after the tour that we met Juanita Martinez. A noted maker of storytellers, she operates a small shop out of her home, one of about 25 shops on the plaza. Years ago we bought a small Martinez storyteller from the Carson House Shop, a Taos gallery. Now here she was.

She was born on the Jemez Pueblo to the south, married a member of the Taos tribe and remained after he died. The clay she uses is from Jemez and the mountains behind Taos. The Taos clay contains mica, which gives a distinctive sparkle to Taos pottery.

Most storytellers are made as standing or sitting figures. Lately, Martinez has been shaping lounging storytellers, as if resting under a hot afternoon sun.

“Why are her eyes closed?” I asked, pointing to one I had already decided was a taker.

“Because she’s seeing the story in her mind as she tells it to the children,” Martinez replied.

In her shop, Martinez was selling the 7- or 8-inch storytellers for $85, which I considered more than reasonable. Out of curiosity, we stopped by the Carson House Shop later that day to check its price for one of her storytellers. Oops, just $75. No matter; ours came with its own real-life story to tell.

On and off the pueblos, we talked to Pueblo potters and dealers about prices and concluded that they are as complex and confusing as airline fares. The award-winning potters tend to get the best prices for their work--as much as $18,000 in some cases. Typically, they sell directly to galleries. Others, like Martinez, market at home and in the galleries--some offering the galleries a discount for multiple purchases. A few spread blankets under the portal in front of Santa Fe’s Palace of the Governors, built by the Spanish in 1610. That’s where we paid only $40 for an exquisite little pot by Laverne Loretto from the Jemez Pueblo. We like it as much as the $310 bowl by Angela Baca we’d bought earlier in the day when we visited the Santa Clara Pueblo.

Adding to the pricing challenge, seemingly identical pieces by the same potter can vary widely in price because one reflects better workmanship--although only experts can spot the difference. Our rule of thumb is to buy what we like and can afford--preferably from the potter.

Santa Fe, set in high desert country at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, is a highly sophisticated, arts-oriented community. It is known for excellent museums and dozens of galleries. Nowhere else in the country is there such a concentration of art within easy walking distance.

If you’re not familiar with Pueblo pottery, the best way to get started is to browse the major pottery galleries in Santa Fe (Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery or Packards) and in Taos (Carson House). This will introduce you to the work of some of the best potters, many of whom you can visit on their pueblos. Also spend an hour or two at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe, where pottery exhibits detail the pueblos’ differing styles. Look for symmetry, uniform glossiness and clear, neatly executed decorative images.

On a visit to Packards in Santa Fe, we sought advice from manager Don Davies. Beware of “greenware,” he warned. This is pottery made of liquid clay poured into molds, and it’s hard for amateurs to distinguish from a hand-worked pot. One giveaway is pottery that’s advertised as “Pueblo painted.”

Of course, we didn’t know any of this 14 years ago. We were just lucky. Back then, the first pueblo we visited was San Ildefonso, about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Occupying 26,000 acres, it is on flat, arid land at the foot of low brown hills. In the village, a little Spanish colonial church and one-story adobe homes are clustered around a dusty plaza. About 700 tribal members live here.

One of the most famous pottery pueblos, San Ildefonso was the birthplace in 1887 of Maria Martinez, who is credited with sparking a pottery-making renaissance throughout the Southwest. Her black-on-black pots are expensive collectors’ items. But in a small pueblo gallery that first day, we bought a lovely bowl made in the Maria Martinez style by her grandniece, Helen Gutierrez.

A day or two later, we learned that Gutierrez had been recognized for her pottery at that summer’s Indian Market in Santa Fe. And then we spotted one of her bowls on display at the delightful Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos. Our little pot, it turned out, boasted impressive credentials.

In July we returned to San Ildefonso, hoping to find Gutierrez, whose work now is included in the collection of the Museum of Indian Arts. The village still looked worn and dusty, a quiet place where a trio of dogs napped in the shade of a towering cottonwood. At the visitor kiosk, we paid a $3 parking fee and picked up a map to the pottery shops. Enter anywhere a sign reads “Pottery--Welcome,” the clerk at the desk said. When I asked, we were told that Gutierrez died a few years ago.

As we headed on foot to the pueblo museum, a couple of boys sped past on wobbly bicycles, waving vigorously and erasing any lingering fears that we might be intruding. Several times we stepped indoors to find ourselves in a family living room, a corner of which served as a pottery shop.

At the museum, an exhibit described how pots are made. Local red and white clay is gathered and shaped into slender coils that are stacked one on top of the other, then smoothed by hand--not with a potter’s wheel. A fine slip of water and clay is applied. Then the final polishing is done with a stone, and a design is painted on.

Now comes the tricky part: the firing. This is done not in a kiln but outside over a grate. Cakes of dried manure are stacked around the pots and set afire. The pot may emerge red in color. Or if black is sought, the fire is doused with pulverized manure, producing a blackening soot. It’s not unusual for carefully worked pieces to crack or become badly smudged.

At the Aguilar Indian Arts shop, a father-and-son operation, I asked son Michael Aguilar how long it took him to complete a small pot this way. “About 20 hours,” he said, displaying a small, graceful red pot priced at $239. Aguilar has adopted a technique popular with younger potters called sgraffito, which involves scraping through the slip before firing to expose the clay underneath. On this pot, Aguilar had etched a kokopelli, the Indian flute player. It came home with us.

My reporter’s instinct compelled me to ask whether potters were ever willing to negotiate. “Some potters deal,” he replied, “and some don’t. You’ve got to ask. In summer we get lots of buyers. If I don’t sell today, I’ll sell tomorrow. In winter we see fewer people. If a potter has got lots of pots, he may deal.”

Some potters--like the acclaimed Barbara Gonzales, whose shop, Sunbeam Indian Arts, is a few steps away--are decorating with turquoise inlays in addition to sgraffito. All of the Gonzales family--husband Robert, four sons and grandchildren--are in the trade. “It runs through the genes,” said Robert, noting that his wife is the great-granddaughter of Maria Martinez. As might be expected, even Barbara’s smaller pots are pricey, beginning at about $450.

Santa Clara Pueblo, a 10-minute drive north, is the premier pottery-making reservation. An estimated 400 potters in a population of fewer than 3,000 produce highly polished red or black pieces, many bearing the design of avanyu, a water serpent. Here we stopped at Merrock Galeria, the shop of Paul Speckled Rock. He told us so much about his aunt Angela Baca--we had seen her pots in fine Santa Fe and Taos shops--that we had to take home a large, elegantly shaped orange bowl with deep pleated ridges. Price: $310.

About 15 miles away at Bandelier National Monument, site of ancient Anasazi cliff dwellings and caves deep in Frijoles Canyon, the museum shop offered a similar bowl for $345. “Good for us,” I thought. In Santa Fe, at the museum shop in the Palace of the Governors, the price for a seeming duplicate was $250. Who can explain it? Anyway, we know Baca’s nephew. That’s something of a story.

For a dramatic setting, head for the pueblo of Acoma, 45 miles east of Albuquerque. Sky City, the ancient home of the Acoma Indians, sits atop a sheer-faced, 367-foot-high mesa. A few families still live year-round in the terraced adobe dwellings, another of the oldest communities in the U.S.

To enter Sky City, outsiders must take an hourlong tour ($10). Once, only guarded secret trails ascended the heights; today a paved road climbs in steep curves, and we were escorted up in a small bus. After the tour we were invited to descend one of the old paths.

The Acoma are skilled pottery-makers. Their hand-molded pots are noted for thinness and intricate geometric designs, painted in black, red and shades of orange. A dozen or more potters--there are hundreds on the 345,000-acre reservation--display their craft in Sky City’s narrow streets.

While I chatted with a couple of women selling hot Indian fry bread, Sandy ducked away to buy (for $65) a small multicolored pot. She handed it to me as we made our way to the steep downhill path. Never sure-footed, I slipped, cracking the pot as I fell to the ground. At home we patched it up, and only we know of the break.

That’s the story this little souvenir tells.

James T. Yenckel is a Washington, D.C., travel writer.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.