- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 12, “Commitment (The Woo Woo Issue),” where we explore why Los Angeles is the land of true believers. Read the whole issue here.)

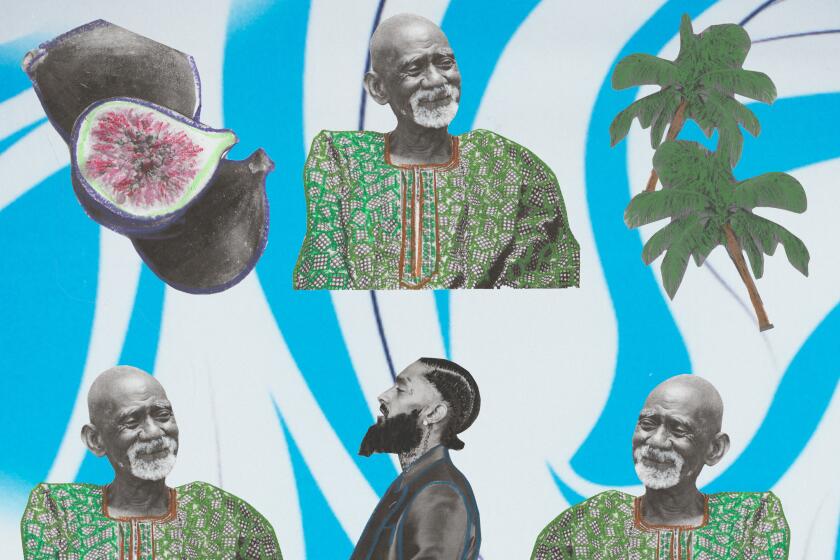

Due to international and national emigration in America, which took place in the 19th and 20th centuries, Black cultural traditions and East Asian spiritual philosophies and customs have continued to overlap, intersect and converge in California. The work of geometric abstractionist Matthew Thomas is in some ways a product of these encounters that happened during the expansion of the West. Thomas and his oeuvre have made evident the visual and spiritual intersections that persist between Black Americans and Asian communities that both uphold certain spiritual practices and philosophies, which enable survival in an oppressive world.

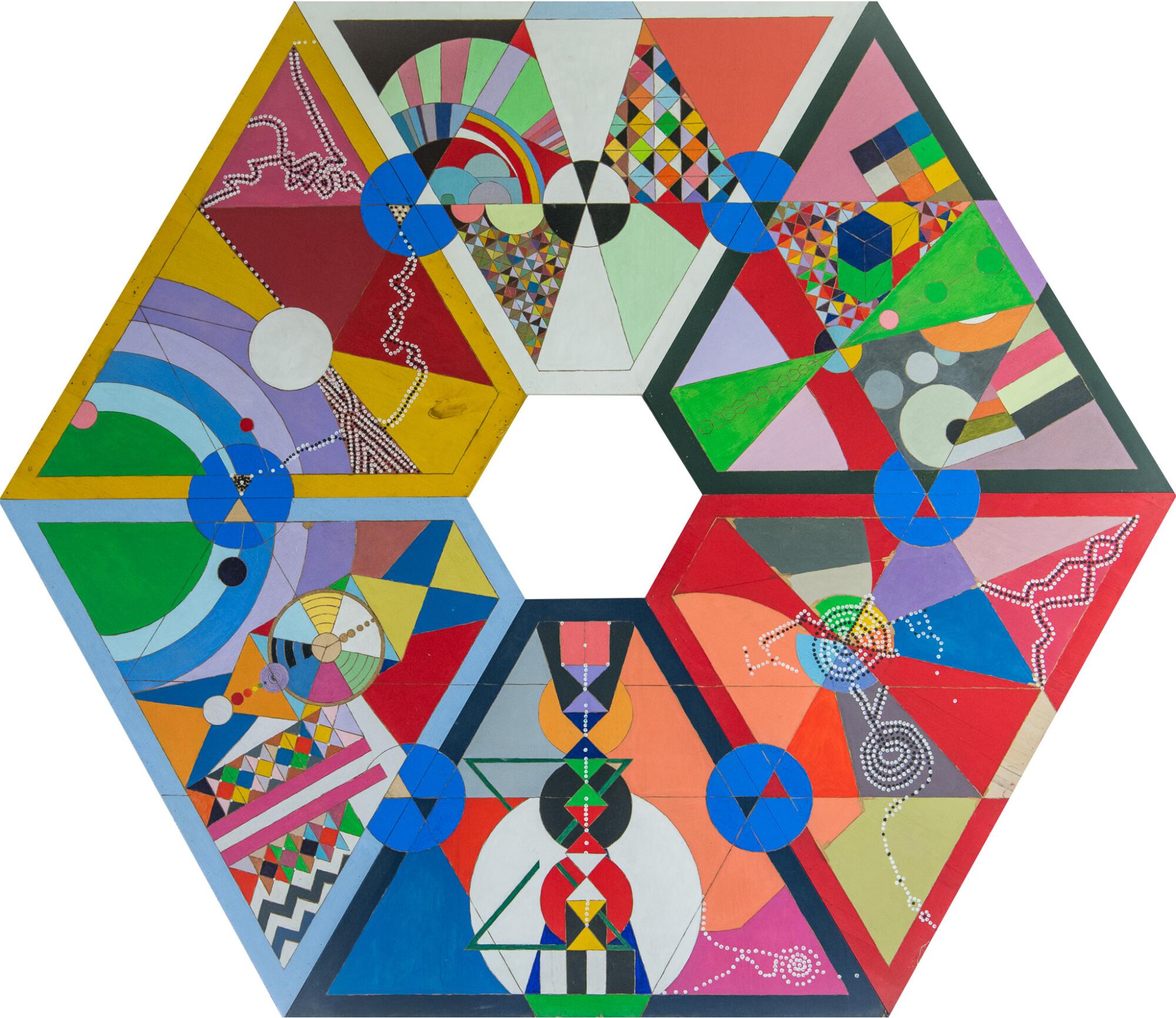

As a practitioner of Eastern religions and of the vibrant history of Black migration from the American South to Southern California, Thomas is well versed in the importance of ritual and history. Eastern religious practices and Black American abstraction impulses are both practices that provide a sense of freedom and agility of faith through visual art forms and varied experiences of enlightenment. Thomas captures the beauty of informal expression through visual signifiers — line, shape, color and texture. And he utilizes these elements in his artmaking to encourage viewers to be most present with themselves and others.

Thomas, 79, is known in Los Angeles for his distinct color palette, where he often incorporated clay and mud into paint pigment for his paintings. For several decades, he worked as an artist and educator in Los Angeles before retiring and moving to rural Thailand in 2011. In Thailand, he has continued to deepen his commitment to his spirituality, living a life of solitude (with his wife). He spends much of the day meditating which informs a wide range of primarily two-dimensional paintings.

The Buddhist tradition defines enlightenment as a metaphysical experience where one contends with self-realization and accepts the reality of the world around them. In his recent exhibition “Enlightenment,” at the California African American Museum, Thomas sought to expand on the term to offer his own definition in relation to visual art:

Enlightenment is a sincere effort to bring elements of

art as messengers of our potential divinity. There are

as many ways to reach source as there are people.

Each person has a connection to divine nature. This is

one aspect; using visual perception to awaken oneself.

In the Buddhist tradition, one takes refuge in the fact that suffering is inevitable. For a Black Buddhist, this acceptance on the journey to enlightenment becomes especially difficult, in the wake of continued anti-Black violence. As a practitioner myself in the faith, I have found solace in my professional collaboration and fellowship with Thomas, but I have also found restored faith in my own practice by witnessing Thomas’ enduring faith, positivity, kindness and healing even in the wake of so much grief. In June, I met with Thomas from my L.A. office via Facebook video chat (his only form of communication), as he was in his home studio in rural Thailand.

Taylor Renee Aldridge: I want to begin by talking about your spiritual practice, as your spiritual and your artistic practice are intertwined in many ways. Can you talk about or recall when you were first exposed to Buddhism in California?

Matthew Thomas: So my first introduction to Buddhism wasn’t formal. It was informal. I grew up with Japanese, Mexican American and African American kids. One of my high school girlfriends was Japanese. We would go to the Buddhist temple on Saturday night to dance.

I didn’t know what Buddhism was at that time, but that’s what we did — maybe once or twice a month for quite a while. That was my informal introduction. Another informal introduction was when I came back from Hawaii, about age 22 or so. I was introduced to this temple in Hollywood, and I would go outside the garden and just sit. I learned it was a Vedanta temple — Vedanta is a very advanced Hindu practice. Over time they embraced me; and I was initiated. My initiation was focused on the Buddha. It was practiced through what they call mantra yoga, where you learn to chant and meditate. So that was when I felt the presence of spirit at the altar; it awakened a childhood memory of when I first really encountered not a religion but the actual experience of religion.

TRA: Can you just talk a little bit about that origin experience that you had with altars, within your own family growing up in Texas?

MT: Yes. I lived with my grandparents for the first 5, 6 or 7 years of my life. My grandfather taught me drawing and drafting at a very young age. [When] I was about 5 or 6, [I] was sitting in my grandmother’s sewing room, which was at the back side of the house. It had windows all around, two sides. Very bright. Sitting on the floor, I was doing a floor plan of my imaginary house. And it was a glass, dome-shaped, transparent house. With no interior walls at all. The living space was totally open. During that concentration time is when I experienced my first metaphysical experience. In other words, I could objectively see all the components of my personality and realiz[ed] that wasn’t me. That I was something more transcendent, more silent.

I left it at that, but a couple of days ago, really reflecting on this, I realize that it was my grandfather transmitting his peace to me as his grandson through the artwork he taught me. The only way I could catch it was when I was focused and concentrated on something that I liked. And art was that. So, he really was my first teacher. He did it not through words, not through sermons, but through his very presence and artwork, he transmitted the essence of what religion is about.

That was my real initiation. And that became my guideline or parameter for evaluating spiritual health. The art was completely linked with it. We lived in the racist South, yet I realize now that his power was so protective, we were so peaceful.

TRA: That’s incredible. I want to delve further into the foundation of drafting and geometric abstraction, talking about these geometric sorts of nodes, guideposts, that brought you through to many beliefs and spiritualties. And how the form of abstraction is particularly attractive for people remarking about spirit and omnipresent forces. What about abstraction do you find useful as a form for art-making and spiritual expression?

MT: The first thing I find useful about abstraction as a form is its universality. It can flow between figurative and nonfigurative without losing its content. Abstraction is a concrete way of expressing formless qualities.

Abstraction is based off four elements. One is the point, and then a line, and then a shape, and then color. Using these four elements to construct a map of consciousness or making form out of things like life forces, deities, meditation practices and especially mantra and sacred words. They have no meaning whatsoever in the brain, mind. They are like musical notes that create ambiance and symphonies that embody larger principle. By repeating them, the sounds create light patterns, and these light patterns are geometrical.

So my model for expressing spiritual things are related to frequencies that are tonal and visual. In other words, hearing and seeing the spiritual world. I interpret that, what I hear and see, in terms of geometrical abstractions. It’s the most universal medium, abstract medium, that is a metaphor for those mystical experiences, because experiences are nonrational, and they’re timeless. Yet they’re very scientific. You can train with them through many traditions. But through all traditions in the world, the only way that they are expressed beyond the direct experience is to visual images. And mostly, those visual images when you break them down to their most abstract form, they’re geometrical symbols. The cross, the rainbow, the wheel, the sword — all of these, if you draw them and laid them across each other, they all fit into one geometrical form. So it’s not art in the traditional sense. It’s a sacred image.

TRA: Buddhism accepts suffering and acknowledges that suffering is inevitable. As a Black person practicing Buddhism, especially in this moment, contending with that practice is especially difficult. I just want to hear you reflect on the imminent suffering that we’re all dealing with, and how particular spiritual practices may help us to orient out of that and find light.

MT: Well, for me, the anger and the rage and the self-destructiveness was very subtle. And I was not able to encounter it face to face until I was asked to do Buddhist rituals. I was invited to Japan to do a ritual for world peace, where you’re using fire to purify yourself. This ritual has been carried through for over 1,000 years, and it’s applied to the snakes, but also figuratively. [Laughs] I mean the real hatred, greed and all that. It’s a ritual to expel that kind of energy.

To perform the ritual of lighting that fire was really hard. The one kind of thought was, you are your enemy and yourself, you’re offering the purification of both groups. In other words, all the suffering is not pointed toward the enemy alone. It’s us, too, who are carrying it. Now this is the hardest part: When you get to that soft place of objectivity, where you literally see the enemy’s energy, and you see the effect it has on you, and you also see that the enemy could not exist without you being in front of him. So, there’s a deeper meditation where you are repenting, not only for him but for the dynamics that are happening. That’s when the power’s not passive. It becomes very powerful. The fire purifies us, as well as the enemy. And it purifies it on a very nonviolent level. That same level that my grandfather taught me, you know? It pulls the hate out from the root, so to speak. But it doesn’t do it all at once. It’s a little at a time, you must keep practicing. The weeds keep coming up and keep coming up. You keep pulling. You have two rituals. One is the wisdom to see all this and pull it up — the fire. The other one is the ritual of water. That’s the compassion after you burn the hell out of it.

TRA: Yes, thank you for that, Matthew. My last question for you is, you know, we recently had your exhibition on view at CAAM. The title of that show was “Enlightenment,” which has had a trajectory of meanings throughout modern history. In spirituality, it has a certain significance. Can you talk about what enlightenment means to you in this moment?

MT: It means being responsible. It means, once you’ve seen the truth of our essential nature and you understand the workings of our relative nature, you start the process of healing. Within yourself and in everyone around you. In other words, you honor people. You try to bring out what is best in others.

Taylor Renee Aldridge is the visual arts curator at the California African American Museum.

More stories from Image