He solo kayaked from California to Hawaii. Plus what to do with a backyard bear

- Share via

By Mary Forgione

Welcome to The Wild! (View in web browser here.)

A kayaker hoping to paddle solo from California to Hawaii was recently rescued in rough seas off Santa Cruz just six days into his journey. Cyril Derreumaux told one media outlet that he had hoped to duplicate the “iconic paddle” by Ed Gillet of San Diego, the GOAT of open-ocean paddling.

In 1987, Gillet, then 36, left Monterey Bay in a 21-foot kayak. He turned up on a Maui beach, starving, with hands bloodied by fierce paddling. He hadn’t eaten in four days. It took him 63 days to paddle 2,500 miles.

The longer-than-expected journey prompted relatives, who feared he was lost or dead, to contact the U.S. Coast Guard to search for him. Gillet told the media upon his arrival in Hawaii: “I’m very glad I did it now that I’m here. But there were times during my trip when I thought it was a terrible mistake.” (Read the full story here.)

For people in the know, Gillet endures as a kayaking legend. His story unfolds in “The Pacific Alone: The Untold Story of Kayaking’s Boldest Voyage” by Dave Shively, published in 2018. There was no internet or social media to consult for information on open-ocean paddling. “I was never a meticulous planner,” Gillet told the San Diego Union-Tribune. “When I planned kayak trips, I just threw stuff in and then threw in some more and off I went.” Read more about Gillet in this story.

3 things to do this week

1. Chat with me about outdoors L.A. Why hike in L.A.? There are plenty of good reasons to discover and explore your wild backyard. Join me at 5 p.m. on June 14 in a Zoom chat sponsored by the Pasadena Public Library. I’ll be talking about places you can hike in Southern California, what you need to do to get started, where to go for the best waterfalls or high peaks, and more. It’s free, but you must sign up here to join. The talk is part of “One City, One Story,” which this year features “Leave Only Footprints: My Acadia-to-Zion Journey Through Every National Park” by Conor Knighton, who will be featured on a Zoom chat at 5 p.m. June 24 (sign up here to attend). Get your questions ready!

2. Everything you need to know about gold, rocks and crystals in California. Rockhounds, listen up: There’s still gold (and a whole lot more) in the Golden State. Staffers Andrea Roberson and Casey Miller created an L.A. Times rockhound guide that explains the fine points of looking for tourmaline, blueschist, benitoite and other rocks. It includes photos of each sample, maps that show where to find outcroppings, and explainers on the law regarding each find. Here’s the full story — and happy hunting.

3. Put some sweat equity into local trails by volunteering. Yep, volunteers are gathering again to be good trail stewards by building or repairing trails in the Angeles National Forest. The Lowelifes Trail Crew (named for Mt. Lowe above Altadena) has a work party scheduled for June 13; sign up here. The San Gabriel Mountains Trailbuilders also need volunteers who work on the first, third and fifth Saturdays of the month. Learn more here.

The must-read

Who could resist anything called “one of the best hikes in America?” Times contributor David Kelly goes deep into Buckskin Gulch on the Utah-Arizona border and takes us into the longest and deepest slot canyon in the U.S. “Slot canyons, formed by millions of years of water rushing over rock, are addictive,” Kelly writes. “They draw you in, squeeze you between walls often just inches apart, then throw problems at you — water, mud, debris and the nagging threat of flash floods. Southern Utah has more than a thousand slots, the most anywhere. Some are easy, some are hard. Most are too short. Not Buckskin.” Want to go? Check out the full story and the photos here.

Know this

We’ve all seen it: the viral video of the Bradbury teen who shoved a black bear to protect her pet dogs. The video posted on social media shows the bear and two cubs walking on a concrete wall above the yard. As the dogs bark and advance toward the invaders, the bear starts to engage. In a flash, Hailey Morinico runs out, pushes the bear off the wall, grabs one of the smaller dogs and returns to the safety of her home.

“Obviously we do not recommend bear-tipping,” says Rebecca Barboza, a wildlife biologist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “That young lady was very fortunate that the event turned out the way it did. I think she surprised the bear more than the bear surprised her.”

A lot could have gone sideways. First, the bear appeared during the day, which is unusual; bears typically are more active at night. That may have affected its behavior. Second, the bear was followed by two cubs, which means her response to the yapping dogs could have been unpredictable and aggressive. “The dogs were protecting their habitat, just like the bear was protecting her cubs. But she wouldn’t have attacked the dogs out of nowhere,” Barboza says.

Lastly, the bear could have attacked the teen if it felt on the defense. “The mere presence of a black bear doesn’t mean that people are going to get hurt,” Barboza said. “They aren’t inherently aggressive toward humans.”

What should you do when a bear turns up in your backyard? Stay indoors and don’t run toward it. Period. Before that happens, think about what it means to live in bear country, something Barboza calls having “situational awareness.” Keep your pets indoors and pet food stashed if you live in the foothills or anywhere near the national forests that surround L.A. (Bradbury is on the fringe of the Angeles National Forest.)

What should you do if you meet a black bear on the trail?

If you are near the bear (which you absolutely shouldn’t be), back off slowly and talk in a low, quiet voice. As soon as you get a few feet away, the bear will retreat. “It happened to me numerous times, so I know that works,” Barboza says. If a bear is farther away but in your path, make yourself as big as possible, raise your hands, look at the bear and make lots of noise — and the bear will take off.

What about carrying bear spray? It’s not foolproof. You must be at close range and know which way the wind is blowing to make sure the spray hits the bear and not you. See the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s do’s and don’ts at “Keep Me Wild: Black Bear.”

But back to Morinico. The 17-year-old received lots of media attention after the incident, telling one TV news outlet: “Do not push bears, do not get close to bears. You do not want to get unlucky. I just happened to come out unscathed.” Great advice.

Wild things

Sometimes whole colonies of birds just disappear. After a storm lashed Seahorse Key off Florida’s Gulf Coast in 2015, the 10,000 to 20,000 pelicans, cormorants, spoonbills and others that had nested on the isle for decades were gone. Biologists call it “colony abandonment,” according to this Audubon story, describing it as “so massive, abrupt, and unexpected that they leave behind little more than empty nests and riddles.”

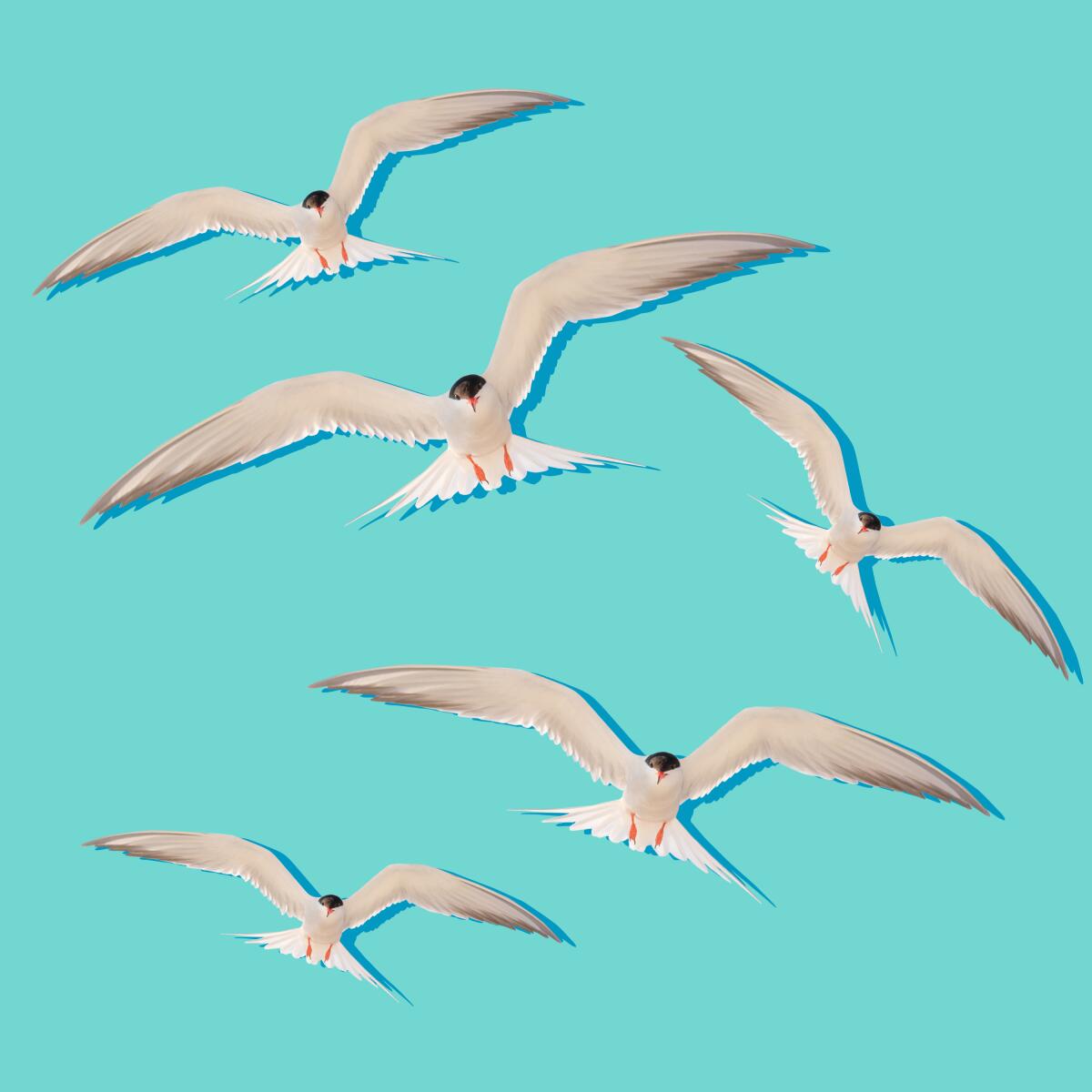

The same thing happened recently in Orange County. Elegant terns that nest at the Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve fled, leaving 1,500 to 2,000 eggs in sand divots on the wetlands. “We’ve never seen such devastation here,” Melissa Loebl, an environmental scientist who manages the Huntington Beach reserve, told The Times. “This has been really hard for me as a manager.” The reason? A drone had crash-landed on the nesting grounds May 12 and scattered the birds. Their whereabouts are still unknown, but the abandoned eggs are a sad remnant of the rookery that once was. Read the full story here.

Social moment

Last month I made my first visit to the Sundial Bridge on the Sacramento River in Redding, Calif. It’s a stunning pedestrian/bike bridge designed in 2004 by Spanish architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava. I looked at the bridge at eye level and then quickly scouted walking routes on the Sacramento River Trail. My friend Joan Schipper lingered, looking up and snapping photos with her smartphone.

I later saw a grid of the photos she posted on Instagram with this commentary:

“Looking up was so mesmerizing I couldn’t find the best angle for the magic. I just kept snapping.

“Later when I opened the gallery on my phone ... the whole panel was the magic! Accidental beauty is a gift out of the blue.”

How did I miss all that? The photos above show the bridge, and the sky-and-bridge angles Joan snapped. If you go, take time to appreciate it.

By the numbers

A recently released field study said blacklegged ticks that carry Lyme disease, something much more prevalent on the East Coast, may be on the rise in brushy areas near Northern California beaches. What about Southern California beaches? “The ticks aren’t on our beaches,” Ryan Hechinger, program director of the Ocean Biosciences Program at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said in an email. “If you tried hard, you might be able to get a tick near a beach by crawling or walking through bushes to get to the beach. ... Even if you did get a tick by romping through the bushes near the beach in SoCal, you’re nearly 100% certain not to get Lyme disease. The Lyme disease bacterium is super-rare in SoCal.” The numbers bear this out.

1970s: When Lyme disease was first diagnosed in Lyme, Conn.

1978: First California case of Lyme disease reported in Sonoma County.

50 to 97: Number of cases reported in California between 2005 and 2014.

20 to 30: Number of cases reported in L.A. County each year (most involve people who contracted Lyme outside the county).

18,000: Number of ticks tested for the bacteria since 1989 by the Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District.

Sources: L.A. County Department of Public Health, University of California’s Integrated Pest Management Program

P.S.

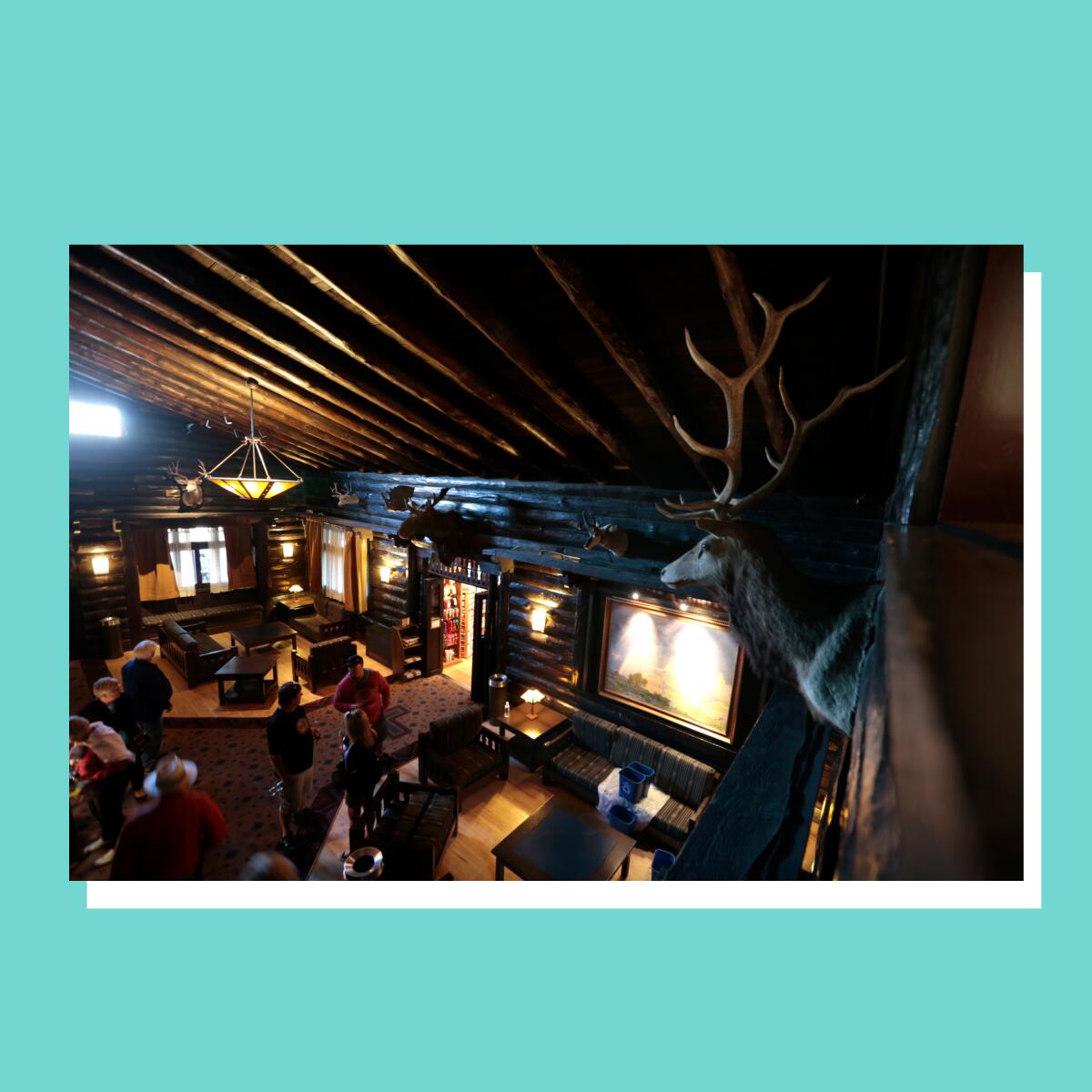

Ahh, summer vacation at your favorite national park is back ... almost. You may not know this, but U.S. national parks rely on foreign students to staff seasonal jobs at restaurants and hotels. Amid the pandemic recovery, student workers who fill positions in Yosemite, the Grand Canyon and other parks are still unable to enter the U.S. because of COVID-19 protocols. “Anywhere you go, you’ve got to be prepared to be patient and be compassionate,” Matt Morgan of hospitality job tracker Coolworks.com told The Times. “The folks that are there are probably working really long hours because they’re short-staffed.” Read the full story about what you can expect at national parks this summer.

Send us your thoughts

Share anything that’s on your mind. The Wild is written for you and delivered to your inbox for free. Drop us a line at TheWild@latimes.com.

Click to view the web version of this newsletter and share it with others, and sign up to have it sent weekly to your inbox. I’m Mary Forgione, and I write The Wild. I’ve been exploring trails and open spaces in Southern California for four decades.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.