One year later: Homeowners share lessons learned from the deadly Woolsey fire

For the survivors, there were some surprising lessons learned, about landscaping and building materials, what happens after the flames go away, and how to prepare for the next firestorm.

- Share via

It’s been a little over a year since the Woolsey fire began its assault on the Santa Monica Mountains, so survivors of that devastation can talk pretty calmly about what they and their neighbors experienced.

They casually point out scorch marks on their remaining trees; the chicken coop that miraculously survived; the sad, scraped earth where their homes once stood — until a breeze comes up. Then their voices tighten, their eyes shift and for a moment they lose focus as they glance to the north, where the wind-whipped flames came roaring through the Malibu hills and upturned their lives, and could easily do so again, as the spate of recent wildfires in Southern California attests.

More than 1,600 structures were destroyed in the Nov. 8, 2018, blaze, which burned nearly 97,000 acres from the Thousand Oaks, Oak Park and Agoura Hills areas north of the 101 to the beach neighborhoods of Malibu. Heavy winds and multiple missteps helped Woolsey become one of L.A.’s most destructive wildfires. Three people caught in the flames died.

At least five others were injured, including three firefighters, and Malibu’s newly elected mayor at the time, Jefferson “Jay” Wagner, who spent two days in intensive care after breathing in carbon monoxide while trying unsuccessfully to save his canyon home. “Some people called it the ‘Yoyo’ fire,” Wagner said, “as in ‘You’re On Your Own,’ or the BYOB fire —’Bring Your Own Fire Brigade.‘”

For the survivors, there were some surprising lessons learned, about landscaping and building materials, what happens after the flames go away, and how to prepare for the next firestorm.

For example, in some instances, oak trees served as “fire catchers” — their leaves and limbs catching embers before they could ignite houses. Healthy, well-tended plants also fended off flames. Wood-chip mulch, by contrast, caught fire and ignited dwellings. Wooden balconies and trellises also caught fire, burning down homes.

Some homeowners who defied calls to evacuate learned that aluminum ladders can melt and that a 1-inch synthetic rubber hose — expensive at about $140 for a 50-foot coil — can be well worth the price if you’re trying to douse embers. (Cheaper, smaller hoses may not put out enough water to be effective.)

Here are the stories of four families and the lessons they learned from the Woolsey fire — some of which run counter to official wisdom and none of which are offered as gospel.

Plant ‘fire catcher’ oak trees and thin chaparral

Leah and Paul Culberg had lived in their stone Lobo Canyon home only a year when the Mandeville Canyon fire ignited a wood balcony, spread to the eaves and burned their house from the inside out in 1978. The fire killed 25 of their animals — poultry, rabbits, a pony, a small herd of goats, two cats and a beloved dog — and blackened their property. They rebuilt, with a metal balcony this time, and Leah Culberg researched landscaping that could help prevent another such loss.

A friend recalled that native oaks are sometimes dubbed “fire catchers” because they filter embers from the air before they can ignite a roof or deck. So the Culbergs dotted the north side of their hill (the side from which fires usually come) with oak trees that have grown and spread over the past 40 years. One seems to be growing out of the foundation, right next to the house. Other large trees loom over the house on the south, running counter to the conventional wisdom to keep the area around our homes clear of overhanging branches.

They also thinned and “lollipopped” the native chaparral growing on the hill below their home, removing the lower branches so none touch the ground: Their gardener does this maintenance every year, removing dead wood and the more combustible “fuel” shrubs, such as chamise.

Leah Culberg is on the board of the Santa Monica Mountains Fund and keen to preserve the native plants of the mountains, but both she and her husband, a former executive vice president of Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, believe these landscaping choices saved their home this time.

On Nov. 8, Leah was at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center waiting for Paul to come out of back surgery when she learned of the fire’s advance. Once she knew her husband would be all right, she, her daughter and her daughter’s boyfriend raced home and “filled three cars to the brim” before driving away around 4 a.m.

When the fire roared though later that morning, their detached garage caught fire (“I think I forgot to close a window,” Leah said), the remaining car in their driveway was incinerated and several perimeter trees were singed, but their redwood pool house with the metal screens survived intact, even though the fire got hot enough to melt a 500-gallon plastic water tank on its eastern flank.

It appears the fire circled the house, consuming the unpruned chaparral across from their hillside home but skirting most of their property. By contrast, some neighbors who had cleared all the brush around their home, or planted vineyards, lost their homes.

In a photo taken shortly after the fire, their property rises from the blackened hills like an oasis.

As convinced as she is that her landscaping saved her home, Leah acknowledges that a shift in the wind could have changed the outcome. The force of the fire and wind blew open a set of French doors, she said, sending smoke and ash into the house, but the embers never ignited. It took nine months for the house and its belongings to be properly cleaned and repaired, and their garage is nowhere near being rebuilt, but at least they are home again.

“You do all this stuff,” she said softly, “but in the end, a good part of it is luck too.”

Charred plants come back

When the fire came, Wagner had a plan. He threw a scuba tank in his pool, in case he had to shelter underwater, and then pulled out his hoses and got to work, dousing his house, his neighbor’s house, and his garage and trucks.

The work was hard because Wagner — owner of Zuma Jay’s surf shop in Malibu and a special effects operator licensed to handle fire — lives on a mostly vertical piece of land. His gardens were terraced, carved into the hill like his three-story home. The only flat spaces were reserved for a tennis court, a long lap pool and a garage. His special effects trucks were parked along the side of his narrow road in Latigo Canyon.

His longtime girlfriend, Candace Brown, an avid gardener, stayed as long as she could until she dropped a heavy canister on her foot and crushed her toes. She drove away as the fire advanced and panicked neighbors followed suit. Moments later, his neighbor Jeremiah Redclay stood on the other side of the canyon and used his cell phone to film giant flames and smoke rushing over a tiny figure that is Wagner, dousing himself with water as the fire blazed by. His box trucks laden with special effects equipment were scorched, as was his garage, but his tools survived and somehow so did he.

His house did not. Wagner is nonchalant as he tells this story, almost good-humored, except when he gets to the part about his aluminum ladder, which melted in the heat. Then all the frustration and futility of that day creeps into his voice. “I couldn’t get the water high enough,” he says. “I couldn’t get it on my roof.” When he rebuilds, he said, he’ll attach a ladder to the outside wall of his house made out of a sturdier metal less likely to melt.

A year after the fire, however, they are nowhere close to getting their house rebuilt. Wagner, now a Malibu councilman, doesn’t want another wood-frame house. He’s researching alternatives, like panels made from concrete with foam cores, but there are questions he can’t answer about how the material would stand up in an earthquake.

Wagner’s insurance has been paying for a studio rental but that money is running out. Some people have moved into trailers on their property as they wait to rebuild, but Wagner chose a different route. He recently poured three asphalt pads on a small patch of level ground outside his garage, and there he’s installing three Tuff Sheds, one for a bedroom/living area, one plumbed as a kitchen and the smallest one plumbed as a bathroom.

“I’ve gone from 4,500 square feet to 350, but at least we’ll be living on the property,” he said. “That will make it easier to get work done.”

There’s lots to clean up, but Wagner and Brown are encouraged by how their garden fared. The apricot tree that burned to a stick sprouted new growth in the spring, as did the scorched citrus trees. Brown’s specialty tomatoes — pea-size fruits that grow in grape-like clusters and pack a wallop of flavor, though she doesn’t know the variety — also grew back this year, without any irrigation, as did the grapevines blackened in the fire. Wagner credits the soil mix in their raised beds, based on the “Mel’s Mix” recipe from “All New Square Foot Gardening” author Mel Bartholomew (equal parts blended compost, coarse vermiculite and peat moss) for retaining moisture and minimizing the damage done by the flames.

A thick row of date palms seem unfazed by the fire, except for a few with scorched trunks. “These are all going to go,” Brown says, but Wagner disagrees. The problem palms, he insists, are the tall shaggy Mexican fan palms and the more graceful queen palms. “The date palms have lots of moisture,” he says. “They won’t burn.”

Fire blew past their moist meadow and air-tight studio

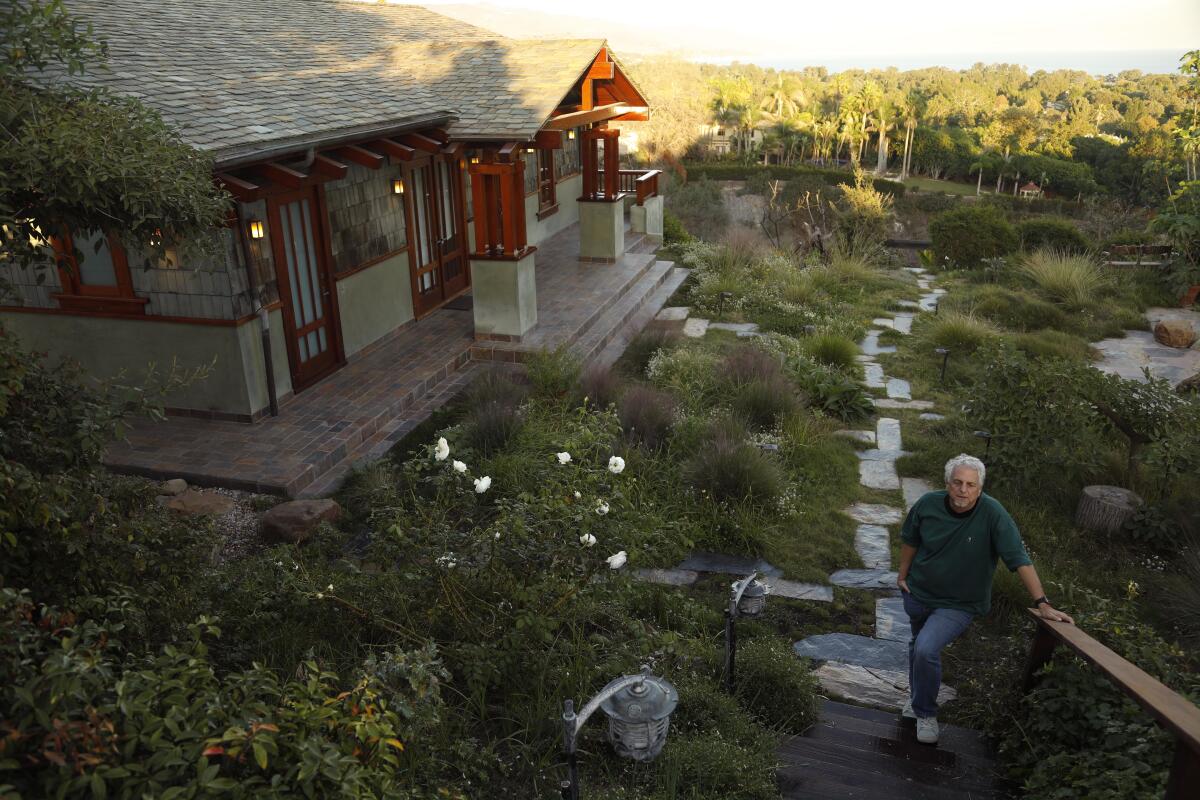

Linda and Richard Gibbs keep their business in the back yard of their Dume Drive property. Richard is a film composer, and his Craftsman-style Woodshed Recording studio, with its cedar-shake siding, slate roof and deck, and lacquered wood trim has hosted many artists. The most famous are invited to sign their names inside the studio’s sleek grand piano — among them Barbra Streisand, Coldplay’s Chris Martin and Chance the Rapper.

The night of Nov. 8, the Gibbses were hosting eight fire evacuees from Calabasas and Agoura. Linda was busy finding places for people to sleep and “calming everybody down,” she said. “I kept saying, ‘It’s going to be fine. Point Dume doesn’t burn.’ Boy, was I wrong.”

She still wasn’t worried the next morning. “The power was out by then, so I pulled everything great out of the refrigerator. I put a great big spread out, and my husband literally said, ‘It feels like the last supper.’”

After lunch their visitors left. “I started to clean up the kitchen, like an idiot,” Linda said, “but finally it started to look hot and red outside, and it was like, ‘Oh, God, we have to evacuate.’ I packed up pictures. My husband packed three guitars, and I took our paperwork and hard drive for taxes, our dog and dog food, and that’s all we got. I forgot the videos; I lost all the videos of our kids.”

Their son’s friend was standing across the gully, hose in hand, when the wind changed. “It just crossed the gully and he watched the front of the flames go right through our property. Those gullies are little waterways that go to the ocean — little conduits for fire — and nobody had been tending them, so there was lots of fuel in there.”

They drove away in separate cars shortly after 4 p.m. as a wall of black smoke pushed into the neighborhood. That night, as they watched a rebroadcast of their house burning, they had no hope that their studio — and main source of income — had survived.

But here’s the thing about recording studios: They are built to be soundproof, said Richard, so that makes them airtight. The lacquered wood trim showed some scorching, but otherwise the fire that destroyed their house left their studio unscathed. “The next morning we walked around the studio and found all these spent embers piled against the doors,” Richard said. “They just couldn’t get inside.”

Another factor was the meadow Linda planted around the studio as part of her interest in the Rehydrate California movement, inspired by climate scientist Walter Jehne, founder of Healthy Soils Australia, to rebuild damaged soil with living plants so that it absorbs and retains more moisture. The “yard” between the studio and pool is densely planted with a variety of sedge grasses and ground covers like yarrow, wild flowers, alyssum and clover, which she waters with sprinklers once a week for about 40 minutes. Near the front of the studio a large coral tree arches over the porch, shading a koi pond. There isn’t a patch of bare earth.

In drone footage taken after the fire, the studio and meadow are a pool of color surrounded by the black and gray remains of more than a dozen homes and yards. That’s because the plants in the meadow were full of moisture, creating a healthy “soil carbon sponge” that repelled the flames, Linda said. They had some wood-chip mulch in the upper yard, near her home, but she won’t do that again. The wood chips burned, she said.

“Soil doesn’t like to be bare,” she said. “When you cover the soil with plants, living roots, you’re building the carbon sponge so the soil absorbs more rain and stays green longer. Everyone talks about capturing rain in water barrels, but the best place to save water is in the soil.”

Richard says he spends all his time these days fussing with the insurance company and construction plans. They will rebuild, but this time with a more airtight design. And Linda has already set her sights on a new landscaping project — to extend her meadow down the slope of the gully, to ensure those plant fuels aren’t around the next time fire comes to call.

Yes to good garden hoses, no to wood chips

Mikke and Maggie Pierson woke up around 2 a.m. Nov. 9 to take in her sister’s family after the fire forced them to leave their Malibu Lakes home. By 6 a.m, Mikke Pierson told his wife it was time for them to leave too. “She packed up all our valuables, jewelry, paintings and photos and then the bedding and clothing went next. They filled three cars, and I finally told her, ‘Honey, you can’t pack the washer and dryer.’ She would have pulled the siding off the house if she could have.”

After his wife, daughter and sister-in-law drove away, Pierson stayed with his adult son, Emmet, and about six neighbors to protect their homes. (In retrospect, Pierson does not advise this: “When I talk to people today, I tell them absolutely don’t stay.”)

In the end, he said, their success at saving houses was largely dependent on the garden hoses people left behind. At one house, for instance, a small pile of leaves ignited the garage door, which was just starting to burn. “I thought, ‘I can get this,’ but when I turned on their hose, nothing happened. It was a flimsy hose and very old pipes, so there wasn’t any pressure.” The fire devoured the house.

The outcome was different at his neighbor’s house, where he found a 1-inch heavy-duty synthetic rubber hose with a fire-spray-type nozzle. “The house tried to burn multiple times, but we were able to save it. People with 1-inch garden hoses and good (water) pressure saved a lot of homes.”

At another property he was stunned to see an entire yard in flames from the wood chip mulch that had caught fire. The flames were moving to the house and could have set it on fire, he said, if he hadn’t watered them down with a garden hose.

His metal-roofed house with stucco exterior and fire-resistant Hardie board under the eaves survived without any exterior damage, but piles of fine ash still sifted inside through the skylights months after the fire ended. “It didn’t stop until the rains came and settled the ash,” he said.

Their landscaping of sedge grasses, bottlebrush and strawberry trees was untouched too, except for some scorched lavender.

What’s most important, Pierson believes, is that his plants were healthy and well-pruned, without dead wood or dried out debris that could easily ignite. “There’s a lot to be said for maintaining your trees — keeping them trimmed and clean, with no loose bark. Healthy, well-maintained plants are not going to burn.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.