How prostitution is ‘modern-day slavery,’ and what law enforcement is doing to stop it

- Share via

reporting from SANTA CLARA — The customer has no idea what he is walking into. He is in his early 30s, dressed kind of schlubby, and wanting to buy some sex on a gorgeous weekday afternoon a stone’s throw from Levi’s Stadium, home of Super Bowl 50.

He knocks on the door of Room 141. It opens. He disappears.

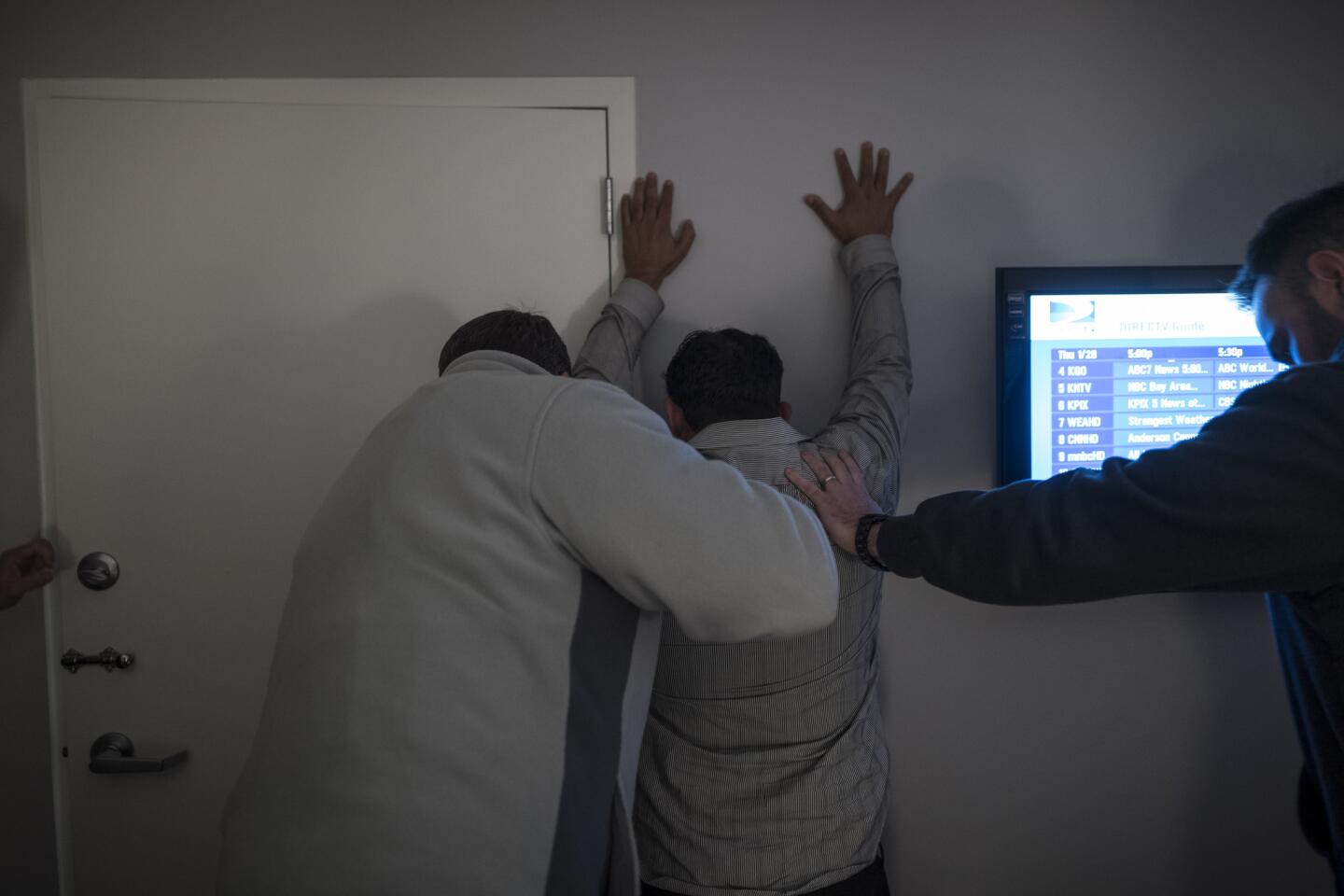

There will be no happy ending for him today. He will be greeted by a Santa Clara County sheriff’s deputy who is posing as a prostitute. Several law enforcement officers will stand with her, just in case. Should he try to flee, he will be stopped by officers who are watching unobtrusively outside.

The man will be cited for engaging in prostitution, a misdemeanor.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

While this is going down, Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Sgt. Kurtis Stenderup’s phone never stops dinging with text alerts.

He runs the sheriff’s Human Trafficking Task Force, and he is coordinating the arrival of prostitutes who have been lured to the hotel by undercover officers, the arrival of men like the one who was just caught and the movements of 12 deputies in six unmarked patrol cars around the perimeter of the hotel who are hoping to arrest the real targets of this operation, pimps.

A few minutes later, Stenderup takes me into Room 141. The schlubby man is sitting on the bed, looking slightly dejected. A couple of deputies are standing over him. The “prostitute” he was coming to see is a youthful sheriff’s deputy, dressed in jeans and a casual shirt.

Elsewhere in the hotel, a 27-year-old woman with heavy eye makeup and a short, short skirt is sitting on a bed looking concerned. She is a prostitute, who, like the man, was solicited on backpage.com, a popular prostitution website. She had come to this room thinking she was about to have a “date.”

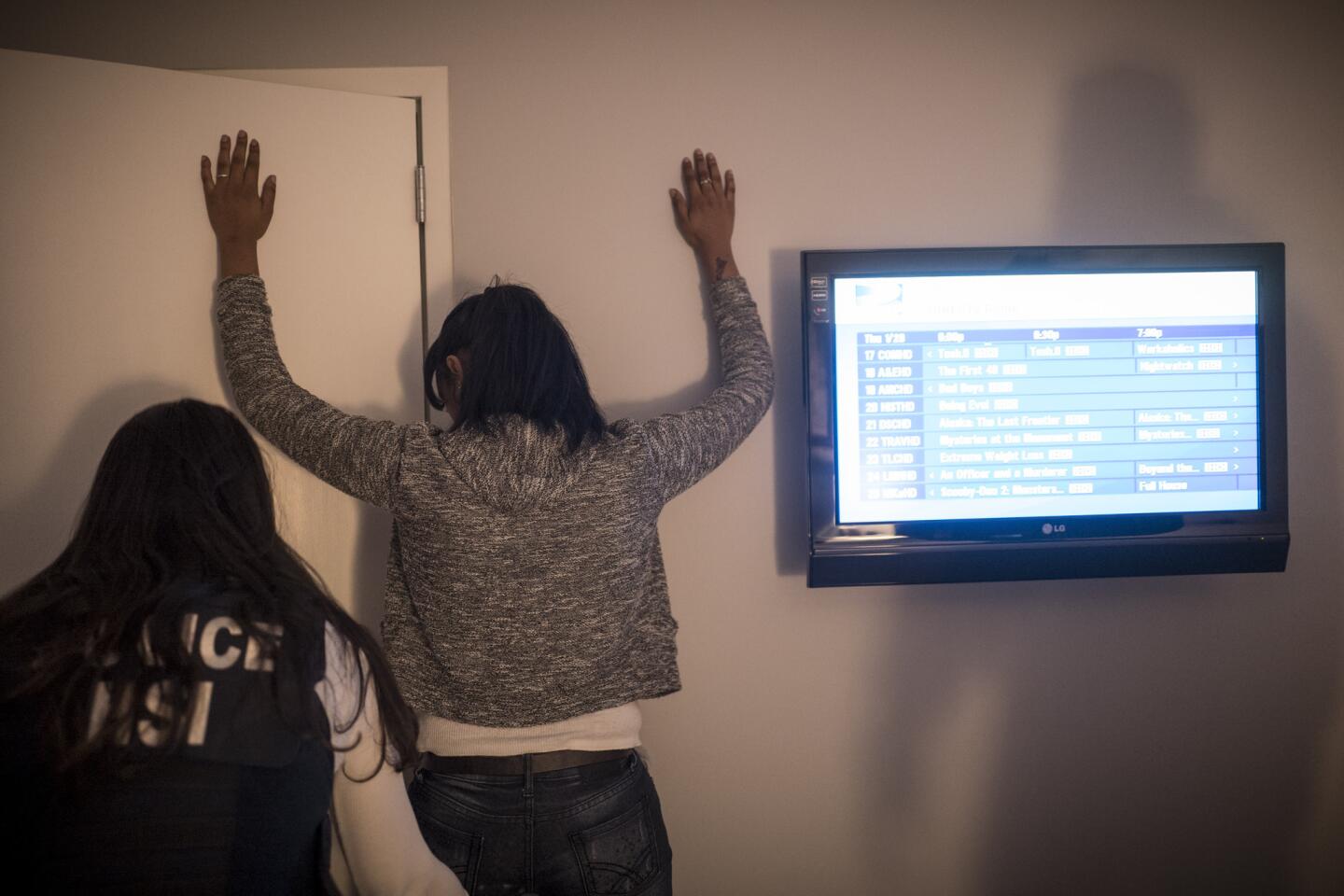

Instead, she is being interviewed by trained advocates from the YWCA who are looking for signs of coercion and fear. They will offer her clothes, resources, shelter. She will not be arrested or cited. The presumption is that she is a victim.

This is modern-day slavery. Our ultimate goal is the recovery of minors who are human trafficking victims.

— Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Sgt. Kurtis Stenderup

These days, law enforcement is centered on ferreting out exploitation and stopping it. “Whether it’s in sex trafficking or labor trafficking,” Stenderup said, “we’re looking for the exploiters. This is modern-day slavery. Our ultimate goal is the recovery of minors who are human trafficking victims.”

::

Every year, before the Super Bowl, the stories start: Thousands of prostitutes — 10,000, maybe — descend on the host city. Testosterone-charged men, with disposable income and away from their moorings, go looking for fun. Sounds plausible, right?

Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, an associate professor at Arizona State University and director of the school’s Office of Sex Trafficking Intervention Research, and some colleagues decided to find out. In 2014, Roe-Sepowitz directed a two-year study looking at whether the Super Bowl leads to an increase in sex trafficking.

The researchers looked at online ads, placed decoy ads to gauge demand and tracked the migration of cellphone numbers among geographic locations. They developed a matrix for likely exploitation of a minor, and forwarded tips to law enforcement agencies in New Jersey and New York for the 2014 Super Bowl and Arizona for the 2015 Super Bowl.

Each decoy ad got an average of 63 calls a day, and text exchanges like this one, from last year: “I’m here from Seattle and after yesterday’s game outcome I need a little cheering up. R U up for hanging out with me for a gfe hour?” (The Seahawks lost the 2015 Super Bowl to the New England Patriots. “Gfe” means “girl friend experience,” i.e. sex with kissing and cuddling. I refuse to get any more detailed than that.)

Researchers found that the online market for illegal commercial sex is huge and growing, and its sheer volume overwhelms the capacity of law enforcement to respond in a way that might truly dent the problem. But they did not find a causal link between the Super Bowl and sex trafficking.

“We don’t have any evidence that girls are being kidnapped off the street for the purpose of the Super Bowl,” said Sharan Dhanoa, coordinator of No Traffick Ahead, a multi-agency work group that focuses on sex and labor trafficking. “What’s more likely is that individuals who are already exploited will be moved around.”

Ultimately, the researchers could not say that the Super Bowl in and of itself is some sort of sex trafficking magnet. Traffickers simply go to where there are large concentrations of people, mostly men. When the Grateful Dead played Levi’s Stadium in June, Stenderup said, his colleagues noticed a bump in online sex ads.

Maybe if word about this sting gets around, some traffickers will stay away from this year’s Super Bowl on Feb. 7. The idea is to depress the market.

::

As we sat in a sunny hotel courtyard, four officers were talking in the parking lot to a man they believed might have dropped off the 27-year-old prostitute. They were trying to discern whether he was her pimp. His white SUV reeked of pot, which gave them an opening to chat.

Stenderup’s office, acting on a tip last week, made contact with a 15-year-old who was being trafficked by an 18-year-old pimp, he said.

“We find that most exploiters are in their late teens to early 20s,” Stenderup said. “We do not see a lot of old men.”

The teenager was angry at first, and refused to talk. But after spending time with an advocate from the YWCA, she changed her mind. Investigators are building a case against her pimp.

A few yards away, in one of the hotel rooms, authorities were waiting for a male prostitute who had arranged to service a decoy client. As he pulled up, the man saw the deputies talking to the suspected pimp and got nervous, or “hinked up,” as Stenderup put it, and quickly drove away. Half an hour later, another very young-looking male prostitute arrived and was ushered inside.

As I drove away, I saw him standing in front of the room, chatting amiably with an advocate. I may have imagined it, but I’m pretty sure he looked relieved.

Twitter: @AbcarianLAT

ALSO

Church bans TV host ‘Mr. Wonder’ over sex abuse allegations

Why an ESL teacher might have helped 3 O.C. inmates escape

LAPD detective is accused of intimidating and threatening her ex-boyfriend

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.