From the Archives: She forgave the father who shot them all

- Share via

She blinked and wondered how long she had been asleep. She saw the Chanel ads and Vogue magazine pages taped to her white walls. She blinked again. Her head pounded. She saw the photos of her high school friends tacked to a bulletin board. Bin Na looked up at her twin bed. Why, she wondered, was she on the floor? Why was her head throbbing?

It was Saturday, April 8, 2006, but Bin Na Kim did not know it. All she could remember was the day before--her last day of school before spring break at the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies. Bin Na, a 16-year-old sophomore, had eaten lunch with friends in her math classroom. She could not stop talking about New York. She would fly out the next evening with a classmate. They would tour New York University. They had tickets for "Chicago," the Broadway musical. Bin Na had arranged to borrow her best friend's gray peacoat.

Now, on her bedroom floor, Bin Na worried. Could it be Saturday already? What time was it? If this was Saturday, then she had to pack. Her flight was at 10 p.m.

Get up, she told herself. She lifted her head less than an inch. The pain knocked her back down. It felt like someone was squeezing her skull, trying to crush it. Her eyes watered. She looked at the white carpet and saw glistening puddles of blood. Bin Na thought she must have gotten her period.

Get up. She tried again. Her head hurt like nothing she had ever felt. Bin Na wailed. Something must be very wrong, she thought. She had to let her parents know she was hurt.

"Matthew!" she called, for her 8-year-old brother.

His bedroom was next to hers. She would tell him to find their parents. Or find the acupuncturist who lived in the apartment next door. The acupuncturist might know what was wrong with her head.

"Matthew!"

No answer.

She called his name again. Still nothing.

"O-ma!" "O-pa!" Mom! Dad!

Only silence.

Again, Bin Na tried to move. Half her body would not budge. Her left arm and left leg sagged as if they were broken. Her cellphone was in its charger, on the floor near her head. She grabbed it with her right hand to dial her parents' number. She could not hear it ringing. She moaned and hung up. She reached for a floor lamp. Wrapping her fingers around its long neck, she tried to pull with her right hand and push with her right foot. Balancing on her right side, she heaved her body up. She stood, bent over, for a second. Then she dropped. Bin Na tried again. Push. Pull. Push. Pull. The lamp toppled, crashing onto her aching head.

Maybe her parents were asleep. Maybe they could not hear her cries. Their bedroom was on the north side of the family's apartment. Bin Na's room was on the south side. A hallway and a living room separated them. Bin Na rolled onto her stomach. She had to get to her parents. She had to let them know something was wrong. Using only her right arm and leg, Bin Na began to crawl.

. . . people said bad things, how he didn't love me. They don't know my dad. That's why I want them to interview me so people know what really happened and can know what he was really like instead of just assuming things . . . my dad is not a bad person. -- Bin Na's journal

Gray peacoat in hand, Deborah Kim waited on Saturday morning at Praise Church of the Nazarene near Wilshire Center. Bin Na and Deborah had been friends since they were 2 years old. Their families both joined Praise Church. They spent Christmas and New Year's Eve together. The girls celebrated their birthdays together. They were like sisters.

Bin Na adored Deborah, a pretty girl with a big personality. Bin Na was pretty too. She spent hours playing with her long, layered hair. She loved shopping for clothes that fit her slender shape. But when Bin Na met new people, she rarely spoke or smiled. They probably figured she was rude, she thought. Really, she was shy.

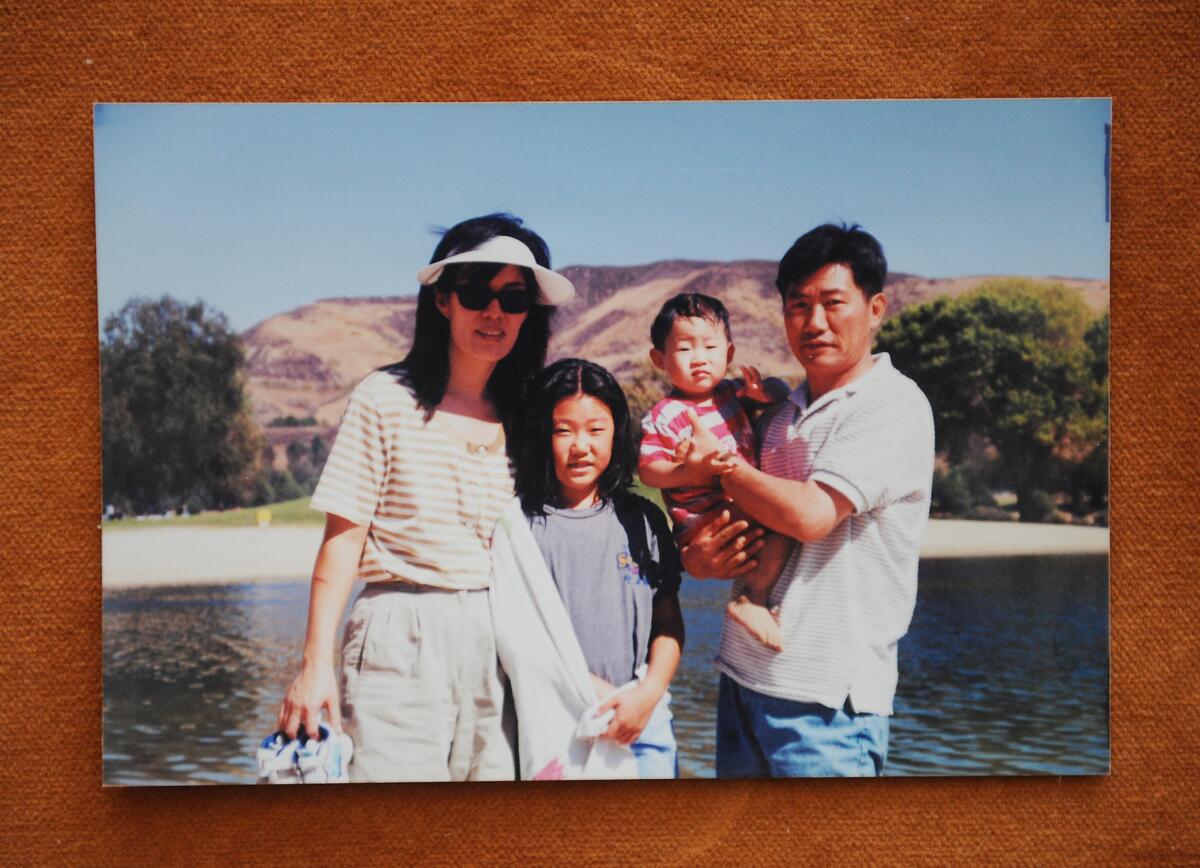

Bin Na loved her father. Sang Kim left Korea in 1990 to live in Los Angeles, where he invested in real estate. He was generous. He took Bin Na and Deborah to Disneyland. He took them to Toys R Us and bought them Barbie dolls. Deborah envied Bin Na. Her father gave her everything she wanted. But Bin Na longed for a father like Deborah's, who hugged his daughter and told her that he loved her. Sometimes, Bin Na would say to Deborah, "I wish your dad was my dad."

Every Saturday, Bin Na took lessons in Korean language and history at Korean school, where her mother, Young Ok Kim, was a teacher. Just before Bin Na turned 8, her mother gave birth to Matthew. He grew into a slight boy, softhearted and sensitive. He cried easily and drew pictures of hearts instead of guns. Bin Na's father did not believe boys should cry. Sang Kim was a proud man, and crying was shameful. "Why are you crying?" he would demand. "Stop." Pride and shame were very important to Bin Na's father. She noticed this about him and about some of the other Korean fathers in her community.

Sang Kim also had a temper. Once, when he tried to teach Matthew the multiplication tables, Matthew did not understand, and his father yelled at him. Matthew started to cry. Bin Na hated it when her father yelled, especially at her brother. She knew how it made Matthew feel. Bin Na had experienced her father's anger many times. She stepped between Matthew and her father. She told Matthew to go to his room. That made her father even angrier. "Am I talking to you?" he shouted at her. "I'm the parent here."

Besides being proud, Bin Na's father was a perfectionist. He tried to hide his weaknesses. But he struggled with English and worried about money. Bin Na knew that her father was ashamed because he could not provide the lifestyle he had envisioned for his family. He wanted a big house. Instead, they lived in an apartment in Echo Park. It had three bedrooms, but it was only an apartment. He had a leased Mercedes-Benz, but his wife drove a Chevrolet minivan.

He told Bin Na to attend a university, so she would not end up like him. She would be successful. He scolded her for not studying hard enough. Bin Na was an average student who did just enough to get by. Her father told her to practice cursive. He told her to chew with her mouth closed. He told her to stand up straight--not to slouch like her mother. He ordered her to speak Korean at home and to speak perfect English in school. He was furious when Bin Na failed a geometry class in 7th grade.

But she knew her father loved her deeply. She knew he wanted only the best for her. He just did not know how to express his love. So he bought her lovely things instead. He came home with bags full of new clothes and trinkets for her. Once, he bought her a $100 Guess jeans jacket. Another time, he bought her two small antique stone ballerinas. She put them on her dresser and hung necklaces on them.

Her father's shopping sprees sparked her fascination with fashion. She fell in love with the clothes he bought. She admired stylish people such as Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen. She loved the bohemian look, big chunky necklaces and fat rings. Friends wrote in Bin Na's high school yearbook: "You have the best style ever." Bin Na also loved the show "Sex and the City." Her parents did not let her have a television in her bedroom, much less allow her to watch a racy HBO series. So Bin Na waited until they were asleep or at church. She watched it in the living room alone, dreaming of such a fabulous and fashionable life.

Deborah wished she had clothes like Bin Na. She wished her father spoiled her like that. In time, Deborah and Bin Na attended different high schools. They did not hang out much outside of church or family events. Bin Na cared so much about Deborah, but she did not know if Deborah felt the same anymore. Deborah knew Bin Na wanted to be a fashion editor in New York, like the character in Bin Na's favorite book, "The Devil Wears Prada." She could not wait to hear Bin Na's stories about Madison Avenue, Times Square and Broadway.

She knew her peacoat would go perfectly with Bin Na's Ugg boots and Seven Jeans. But Bin Na did not come to church to borrow it.

At about 11 a.m., Deborah dialed Bin Na's cellphone. She heard someone pick up. She heard heavy breathing and a soft moan. It sounded like a girl, maybe a young boy.

"Matthew?" Deborah asked.

Click. The phone cut off.

Deborah redialed. Over and over.

No one picked up again.

When we were young, I used to pretend that I just dropped dead. Matthew would call my name and shake me and I would close my eyes and pretend not to hear him and try to lie very still. He'd end up crying and make me all teary. Then he'd smile his big smile and come up in my face. And as we kept playing this game, he found out how to know if I was really dead or not. He'd tickle me. He couldn't stop laughing. I remember his laugh so clearly.

Bin Na paused. She breathed hard. She had managed to drag herself down the hallway, past the guest bathroom. Inch by inch, she kept crawling. Behind her, she left a shadow of blood.

At last, she made it to the master bedroom. There she saw her father. He was lying across the bed on a beige comforter, flat on his stomach. He wore blue sweatpants, and his legs hung off the side. She could not see his face.

"Dad?"

Bin Na thought he was asleep. She crawled toward him and touched one of his legs. She shook it. "Dad!"

But he did not wake up.

Bin Na thought she needed to make some noise. She reached for a radio on the nightstand. She switched it on. Maybe loud music would wake him.

He did not stir.

The throbbing in Bin Na's head beat harder now. She had to get off the floor. She had to get up and wake her father. She looked at the lamp next to the bed and remembered how the one in her bedroom had fallen on her. There was a bathroom off her parents' bedroom. Maybe she could use the bathtub to push herself up. It would not tip over. She dragged herself toward it. She leaned on her right arm and pushed against the tub, trying to stand. She steadied her right foot on the floor and tried with all her might to rise.

But she could not do it.

Exhausted, she rested against the base of the bathroom sink. She found a hand towel and put it over her face.

Time ticked by. Minutes. Hours. She heard a phone ring, then a knock at the front door. She called out, "Hurt!"

Could anyone hear her?

Bin Na closed her eyes.

Sometimes her dad says harsh things about my dad. "Why did you do this? How could you do this to Bin Na?"

He did this out of love.

All day that Saturday, Deborah called Bin Na's friends, including the classmate going with her to New York. The classmate had not been able to reach Bin Na either, and their plane was leaving in a few hours. Deborah called another friend, who had planned to stop by Bin Na's apartment that afternoon to see her off. The friend had knocked on the door--but no one answered.

Deborah told her mother about the strange moans she had heard that morning on the phone. Her mother called a church friend who lived near the apartment and asked her to knock on the door. The friend did. No answer.

Maybe the family had decided to take a last-minute trip, Deborah thought. Or maybe Bin Na's parents had gotten into a fight and did not want to answer the phone. Just as long as Bin Na made her flight, Deborah thought. She knew Bin Na would do anything to go to New York. Sunday morning came. Still no word. Deborah called Bin Na's classmate. Bin Na had missed the plane.

It was April 9, Palm Sunday. At Praise Church, Deborah searched for Bin Na's family among the congregation. They would never miss Palm Sunday services.

Deborah's mother, Mi Sun Kim, and her father, Hyok Dong Kim, feared the worst. They called a locksmith to meet them at the Kim family's apartment. The locksmith jiggled the door handle. It turned. Deborah's parents opened the door. Her mother entered first. She heard a radio in the master bedroom. She walked toward it. She entered the room. Her body went numb. Then she screamed.

Bin Na's mother was lying on the bed, the beige comforter pulled up to her chest. Her head was propped up on a pillow, her neck tilted slightly toward her left shoulder. Dried blood covered her nose, mouth and shoulder. She had two gunshot wounds to the right side of her head, above and below her ear.

Bin Na's father was stretched across his wife's lower legs. He was face down in a pool of blood. He wore a blue sweatshirt and sweatpants. In his right hand, he held a .25-caliber semiautomatic. His index finger was on the trigger.

Their bodies, Mi Sun Kim thought, formed a holy cross.

She cried out to her husband, who had stayed in the living room, too afraid to look. "They're all dead!"

Where were the children? Mi Sun Kim raced into the other rooms. Bin Na was not in her bed. She saw blood on the floor and in the hallway. Matthew was not in his bed either. Had they escaped?

Mi Sun Kim searched Matthew's room. Finally, she noticed a blanket on the floor beneath the bottom bunk. She tugged on it. Under the blanket, in his blue pajamas, was Matthew. Dried blood covered his mouth. Both of his eyes were bruised. He had a gunshot wound to the left side of his head.

Mi Sun Kim had to find Bin Na. Was she dead too? She prayed to God. Let it not be so. She returned to the master bedroom, following the blood streaking along the hallway. She noticed that the bathroom door was open. She went in. There, propped against the sink with a towel over her face, was Bin Na.

Mi Sun Kim gasped. Bin Na's mother, father and brother had turned pasty, but she could see that Bin Na's skin was pink.

She lifted the towel. Bin Na was alive.

"Can you hear me?" Mi Sun Kim asked her. "Everything is going to be OK."

Bin Na did not open her eyes. "O-ma, O-ma," she said, shivering. Mama, Mama. "Don't touch me. It hurts."

For nearly 30 hours, Bin Na had survived a gunshot to the right side of her head, the bullet lodged behind her ear.

I know I have to keep strong for myself and for the people I love.

When Bin Na came to again, she heard a man's voice. "What is your name?" he asked. Bin Na could not open her eyes. They felt heavy, sewn shut. Who was this man? she thought. She remembered collapsing on her parents' bathroom floor. Why was this man in her apartment? Where were her parents?

"What is your name?" he asked again.

Bin Na did not want to tell this stranger too much. She thought quickly. New York City. Madison Avenue. The celebrity Nicole Richie.

"Madison Richie," Bin Na answered.

"How old are you?" the man asked.

"Twenty-three."

Bin Na heard other voices too. Other men. She felt the voices lift her up. Her head screamed. The pain raced through her. She felt them lay her on a hard surface. Bin Na begged, "Put me on a bed, somewhere soft."

"Hold on, we're taking you to the hospital."

Bin Na heard another voice. Someone was talking about her. The voice said she had been shot.

Shot? Bin Na thought. Could that be why she felt so much pain?

"Do you know what happened?"

Bin Na thought hard. She remembered a cafe, a Starbucks maybe, near the Grove, perhaps. It had been nighttime. She remembered standing in front of the cafe, near some tables, on a sidewalk, in a circle with her friends. She remembered a maroon Nissan driving slowly toward them. She did not see the driver. She did not hear gunshots.

A drive-by shooting, Bin Na thought. That must have been what happened. She told the voices, "I was shot in a drive-by."

She said she knows it's really selfish, but sometimes she wished that I was taken too and then I wouldn't have to suffer through all of this. When she said this I realized she's really a true friend.

At church, Deborah paced. She called her father's cellphone. It rang and rang. Finally, he answered.

"What's wrong?" Deborah asked. "What's wrong?"

Her father told her he could not talk. He would tell her later.

Deborah pleaded.

Bin Na, he said, was in the hospital. He had to go. He hung up.

Deborah worried. Had Bin Na argued with her father? Did he hit her? Deborah knew it had happened once before, three years ago. Bin Na told her about it. He had been coming home smelling of alcohol. One night Bin Na greeted him coldly. He wanted to check her homework. She had not completed the last page. She was planning to do it later, or to get the answers from a friend.

Why didn't she work harder? he shouted.

Bin Na shrugged.

Out of nowhere, she would recall, she felt a flash across her cheek. It stunned her. It took several seconds for her to realize that her father had hit her. He had never struck her before, at least not since he had spanked her as a child. Her cheek stung. Tears tickled her eyes. She knew her mother could hear everything, but she did not step in. That was tradition. A Korean mother did not intervene when a father was punishing his child.

Startled by his own rage, Sang Kim apologized. He told Bin Na he did not know why he had done that. He had not meant to hit her.

Bin Na did not speak. But inside, she fumed. He apologized again. She said nothing. He asked her to take a car ride with him. Crying, Bin Na obeyed. She knew where he was taking her. Ever since Bin Na was a child, her father had loved the Santa Monica Pier. Sometimes he would fish there. Occasionally, he brought the family, sometimes only Bin Na. Together, they would sit on a bench and watch the waves, listening to the chimes of the carnival games and the children squealing on the Ferris wheel.

Sitting on the bench that evening, Bin Na could not stop crying. People stared at her. She wanted to go home.

"I'm sorry," her father said again.

For half an hour, they sat there.

"Why are you so angry?" Bin Na would remember her father asking. "Is it because we live in an apartment and none of your friends do? Is the reason you're angry because we don't have that much money?"

Bin Na did not answer.

Then her father drove her to a building in Korea-town. They walked past an empty receptionist's desk and down a hall. He unlocked a door. "Look," he said. "I set up an office. I'm trying to get a business going." Things would get better for the family, Sang Kim said, once his real estate venture started making money.

Bin Na stared at him. He seemed anxious. Why did her father think she cared so much about money? Did he really believe his financial problems made her mad? It was never that. She only wanted him to be a caring father, like Deborah's father, or like her pastor at church, who told his children he loved them. Bin Na told him she did not care about money. "Maybe I have a lot of anger, she said, "because when I was a little kid, you used to yell at me."

His outbursts and reprimands hurt her, she said, even frightened her at times. It felt as if he were a mean boss, not her father. She told him how she wished he were affectionate like other fathers.

Sang Kim listened. He nodded.

"I understand," he said, apologizing again. "I just want you to become a good person." He promised he would try not to get angry anymore. He promised to stop yelling.

He told her, "I love you."

From then on, something changed between them. Bin Na felt her father soften. He did not hit her again. She did not feel afraid of him anymore.

At Praise Church, Deborah remembered this story. Then she noticed: Grown-ups around her were crying. Was it because of Bin Na? What did they know?

No one would say. Deborah kept asking, but no one explained. After the service, two little girls approached her. They had a secret. One of the girls said her mother had told her what happened to Bin Na.

What? Deborah asked. What was the secret?

"Everybody's dead," the girl said, "except for Bin Na."

Deborah did not understand.

"Bin Na's dad shot everybody."

I want to hold my dad's hand and hear him say there is nothing to be scared about, because I know that is what he'd say if he was here right now.

Bin Na's thoughts came in fragments. She knew she was in a hospital. She watched a nurse inject something into her arm. Bin Na drifted off. She awoke not knowing how much time had passed. Nurses were bathing her with sponges.

She tried to tell a nurse, "Call my parents." But her thoughts came out in a whimper. Bin Na felt weak. She drifted off again. When she awoke, she saw Deborah and her family at her bedside. Finally, Bin Na found her voice. "Where are my parents? Where are my parents? Why aren't they here? Don't they know I'm in the hospital?"

Deborah did not know what to say. She told Bin Na not to worry.

When Bin Na woke up the next time, she saw another nurse. Bin Na asked for a piece of paper and a pen. "Call my parents' cellphone," she wrote. All she could think of was that she had been hit in a drive-by shooting, and she had to tell her mother and father. Bin Na wrote down their phone number. The nurse returned. "They're not answering."

Bin Na woke up again. Her mother's cousin was shaking her. Bin Na addressed her as aunt, but Bin Na had never felt close to her. She lived in Los Angeles, but rarely visited. "What are we going to do?" the cousin asked in Korean, still shaking Bin Na's arm. "What are we going to do?"

Bin Na was confused. She was not dead. Couldn't the cousin see that? Bin Na told her, "I'm OK."

"Everyone is gone," the cousin said. Bin Na's father, mother, brother. They were all dead.

Bin Na listened. She said nothing. She felt nothing. It made sense now, she thought. This was why her parents had not come to see her in the hospital. She remembered her unanswered cries in the apartment. She remembered her father's legs hanging off the bed.

She remembered how he would not wake up.

Bin Na did not cry. She did not scream. She did not pray. She did not feel sad or angry. Only numb.

Memories come back so quickly and fill up my head. I miss them so much. I want to talk to them face to face and hear their voices because I know that would comfort me and make me feel safe.

Bin Na was at County-USC Medical Center near downtown. Cards stacked up in her room. "Get better." "You are so strong."

People came to visit. Teachers, church friends, school friends, her pastor, her pastor's family, Deborah's family. They brought magazines: Teen Vogue, W, People, Us Weekly. They brought DVDs, collections of her favorite shows: "Sex and the City," "Will & Grace," "Friends." They brought her favorite movies: "Prime," "Sin City," "Elf." But she was too weak to read or to watch anything.

One friend said, "Oh, you cut your hair." For years, Bin Na had grown her hair long. She layered it and wore it in different styles: straight, wavy, thick curls. Now she touched her head with her right hand. Her hair was short, chopped off near her chin. Doctors had cut it to operate on her head.

One day her favorite math teacher visited. Bin Na did not have the strength to speak to him. She had been given so many painkillers. She could not swallow. She could only nod. During the visit, a nurse tried to suction Bin Na's saliva with a tube. Bin Na knocked the nurse's hand away. She mumbled, "I wanna do it." That was all Bin Na could say, the teacher would recall, but it was enough. Bin Na grabbed the suction tube and did it herself. The teacher knew then that Bin Na would keep fighting.

Detectives visited. They asked Bin Na if she knew who had killed her family. Bin Na said her aunt told her it happened in a robbery. The detectives looked at each other. They looked at Bin Na. "Do you really want to know what happened?"

Bin Na said yes.

Her father shot them all, the detectives told her. He shot her too.

Days passed. The people kept coming. They prayed for her. Cried for her. While she slept, they whispered: We love you. You are strong. You will get better. Through most of it, Bin Na remained numb. She still had not cried or mourned her family. She still had not prayed. She felt empty. Maybe it was the painkillers, she thought. Or maybe it was because she did not want to feel.

Her head hurt. She knew her left side was limp, and she would have to learn how to walk all over again. The left side of her face rumpled like a dress that needed ironing. Nurses put feeding tubes through her nose and down her throat. The procedure burned and made her cry. "Keep swallowing, keep swallowing," the nurses said. They fed her soft food, porridge and shakes. To Bin Na, it tasted disgusting.

One day, the frustration overwhelmed her. She started screaming and thrashing. She tried to rip the tubes from her body. The nurses fastened her hands to the bed. Visitors came. Bin Na begged them to take out the tubes. She was in so much pain. Why had this happened to her? she thought. Why hadn't God taken her too?

To my parents there is so much I want to say, so many things I am sorry for. I wasn't always honest with my mother. I could have treated my brother (Matthew) better. He was really bright. So many things he can't experience now. . . . As I look back, I feel so selfish. There are a million things that I can't face. I keep on thinking about these things over and over and I want to stop, but I can't.

How could her father have done such a thing? Why did he do this? Bin Na tried not to think about him at all. Would she ever understand what her father did?

Or why she lived through it?

Bin Na had been in the hospital for two weeks when a friend she had met at a Christian camp brought his youth pastor to visit. Bin Na was tired. She stared, blankly.

The pastor bowed her head. Bin Na closed her eyes.

"Let her use this as testimony," the pastor prayed. "Let her help people."

All at once, it struck Bin Na. God had saved her. She would get better, and she would give her strength to others. Bin Na would help people. The idea seemed to flicker inside her.

For the first time in days, Bin Na did not feel weak. She did not feel angry.

She felt powerful. Blessed.

Finally, at last, Bin Na cried. She thought of all the visitors who had come to see her. All the people who loved her. She thought of Deborah, who had told her, "Whenever I cry or get frustrated or get mad about the littlest things, I just remember you. You come to my mind. You are so strong."

Bin Na had never thought of herself as strong. For much of her life, she had admired Deborah's beauty and personality. And now here was Deborah, as close to her as ever, telling Bin Na that she gave her strength.

Bin Na had always been a Christian. It was a life she was born into. Believing in God was a given. Church was routine. But now, a week after Easter and two weeks after she had awakened on the floor, Bin Na understood why she had lived.

To help others.

She had never felt so much peace. She felt God's peace. Her thoughts were prayers. They comforted her.

"I will get through this," she prayed. "Just give me strength and wisdom."

I was a little worried that my left arm and leg wouldn't move again because I tell my brain so hard to move them. They just lie there. But I know that it is silly to worry about these things because I know that I'll have my life back, and I have so many great things to do.

The cousin arrived with more bad news. Thieves had broken into the family's apartment and ransacked it. Bin Na's computer, cellphone, iPod, suede ballet flats, collection of jackets, the white shirt from Velvet that fit perfectly, her chunky necklaces, the fat rings, the stone ballerinas her father had given her. Gone.

Her mother's wedding ring too. Even the Chevy minivan.

Why didn't the police patrol the apartment? Bin Na thought. How could the robbers be so evil? Whoever did this, Bin Na hated them.

But time, she reminded herself, was a gift. And she could not waste it on hate.

Bin Na balanced herself on the edge of her bed. It had been weeks since she had stood. Although her left side was still numb, she was beginning to feel the faint flow of blood through her arm and leg.

"Try to move your feet," a physical therapist said.

Bin Na wiggled her toes.

The therapist brought a walker. Bin Na gripped the metal handlebars. Her hands sweated. She leaned into the walker. Her feet tapped the floor.

Shaking, Bin Na stood.

The therapist told her to try to walk.

Bin Na began to waddle.

Oh my God, she thought, I am finally out of bed.

She waddled out of her hospital room and down a hall. Bin Na felt like a 70-year-old, hobbling along. But indeed, she was walking.

A few days later, nurses removed her feeding tube. She could eat regular food now, they told her. Bin Na asked for lunch from Dino's Burgers. She ordered chicken wrapped in tortillas and French fries.

On May 4, Bin Na was taken to Rancho Los Amigos rehabilitation center in Downey. Her new room was brighter and had a big window. On the sill, the cousin placed a photo of her family. It was lonely. The cousin wanted custody of Bin Na. She had directed the staff to restrict visitors, including Bin Na's pastor and his family. If Bin Na had her choice, she would have preferred to live with her pastor's family or with Deborah's.

Bin Na cried and begged. The cousin finally lifted the visitor restrictions. Deborah's older sister, Davina, came to visit.

Did Bin Na know about the letter?

It was her father's suicide note. Parts of it had been published in the Korean Central Daily News. The cousin had showed it to a reporter there. Bin Na asked the cousin to show it to her. She wanted to know what it said--but she also wanted to see her father's handwriting. Seeing his handwriting might somehow help her.

The letter was addressed to their pastor at Praise Church. Bin Na could make out only parts of it because her father had written in a style of Korean she did not understand. It read: "Please take good care of my beloved Bin Na and Hyun Tae (Matthew)." Her father wrote that he had loaned acquaintances $75,000, and the money had not been repaid. He asked the pastor to collect what was owed to his family. He wrote that he had also borrowed money and bought land with church members. He asked the pastor to "please give the shares to my children later on." He wrote that he was torn between suicide and his faith. Bin Na realized that her father had intended to kill himself, but had not planned to kill his family. She thought he must have decided at the last minute that he did not want them to carry his disgrace.

The letter ended:

I sincerely beg you to forgive me

April 6, 2006 9:57 p.m.

Sinner, Sang-In

Until she saw his letter, Bin Na did not know the extent of her father's financial problems--or the weight of his shame.

She thought about his generosity, how he had bought her whatever she wanted. She thought about his pride and about his desire to give his family the best. It was a burden, she realized, that had caused him great pain. For weeks, she had struggled to understand what had happened, and now she did.

If only she could have convinced her father that money did not matter. If only she could have convinced him that the only thing that mattered was love. The love he had for his family. The love his family had for him. The love Bin Na had for him. She could not hate him. She forgave him.

Love, she realized, was stronger than bullets.

I want to tell as many people as possible. Someone needs to tell them why these things happen.

The Friday night youth service at Praise Church of the Nazarene pulsed like a concert. About 35 teenagers, mostly high school and college students, had gathered for the June 2 event. Bin Na had chosen her outfit carefully: a checked headband, baby blue cargo shorts, ballet flats. A week earlier, the youth pastor had asked Deborah if Bin Na wanted to give testimony. Bin Na said she would be honored to.

She had been released from Rancho Los Amigos and had moved in with Deborah's family under a court-approved custody agreement. Bin Na still could not walk for long stretches. Sometimes she used a wheelchair or a cane. Sometimes she wished she could just fly.

Bin Na did not have enough coordination yet to style her short hair. Deborah and Davina helped her. Bin Na had always been like a sister to both of them. Now it was official.

Some days, Bin Na did not feel like getting out of bed. Other days, she felt happy to be alive. She planned to re-enroll in school and graduate with her class. "I'm not going to be those people that just stay in their room and cry," she said the other day. "All the doctors ask, 'Do you have any ideas of hurting yourself or killing yourself?' I'm like, 'No. I'm going to get through this. Even though it's really hard.'"

When Bin Na arrived at the church, her friends ran to her. They hugged her. She took a seat next to Deborah in a front-row pew. Someone was onstage singing. Bin Na looked at the program and saw her name. She began to tremble. She looked at Deborah. "I am getting nervous."

"Next," came the announcement, "we have a testimony by Bin Na Kim."

Bin Na stood. The audience applauded. She walked slowly, using a cane. The audience fell silent as she climbed the stairs leading to the stage. She felt as if she were about to ride a roller coaster. She stopped in front of a lectern. She saw people who had visited her in the hospital, people she had grown up with. This was her family now.

Bin Na spoke with quiet conviction.

"I didn't know that so much could be taken away from me," she said. Her voice quavered. She felt her throat tighten. Her eyes brimmed with tears. The audience became a blur of faceless, sobbing, sniffling heads.

"I know that God's with me," Bin Na said. "Every step. And I'm going to get stronger."

I know my dad is smiling down on me. I know my dad is really proud of me.

An update on Bin Na Kim's story: Don't think of the lone survivor of her father's murder-suicide as 'that poor girl'

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.