Oakland under scrutiny over lack of safety inspections of Ghost Ship before catastrophic fire

- Share via

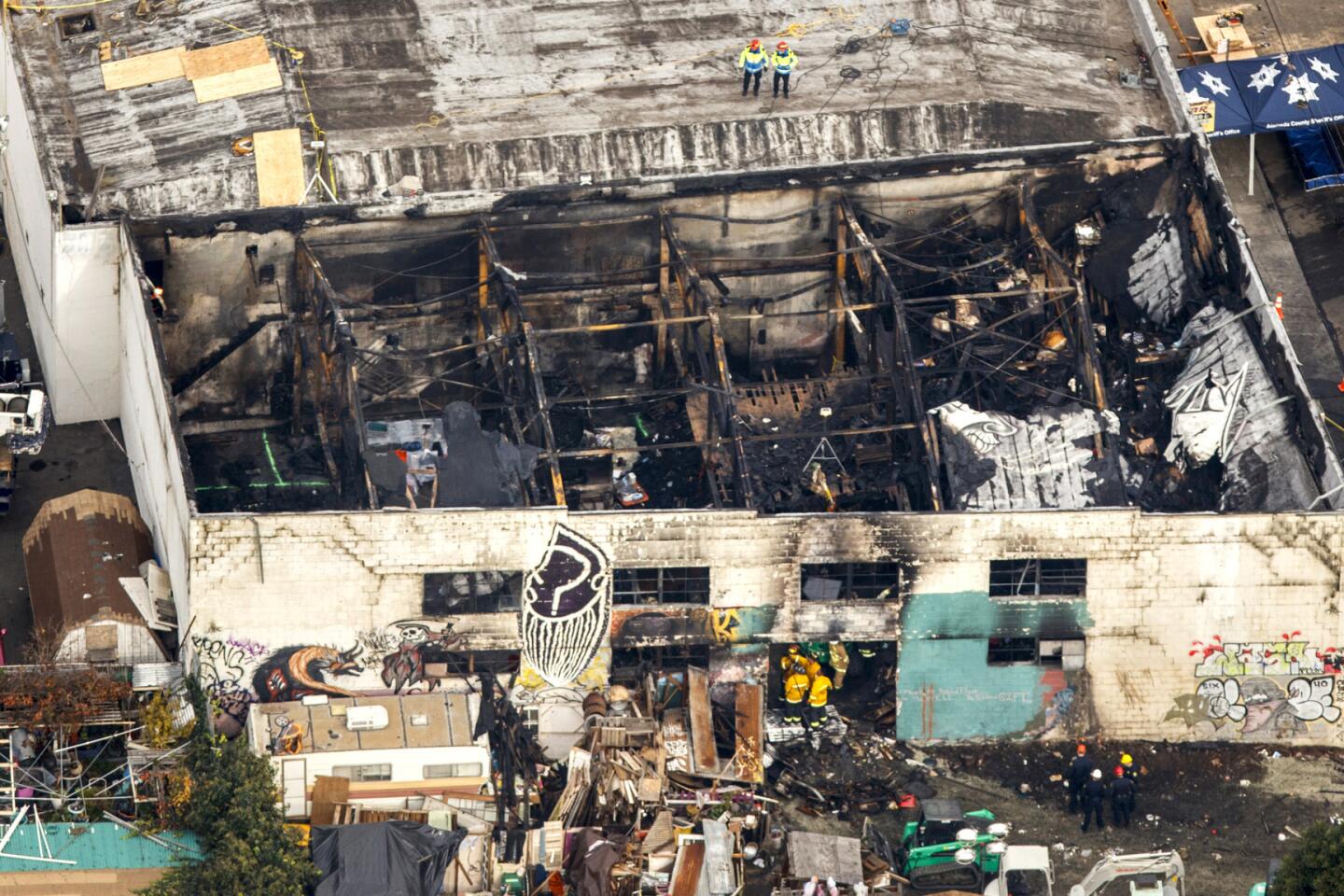

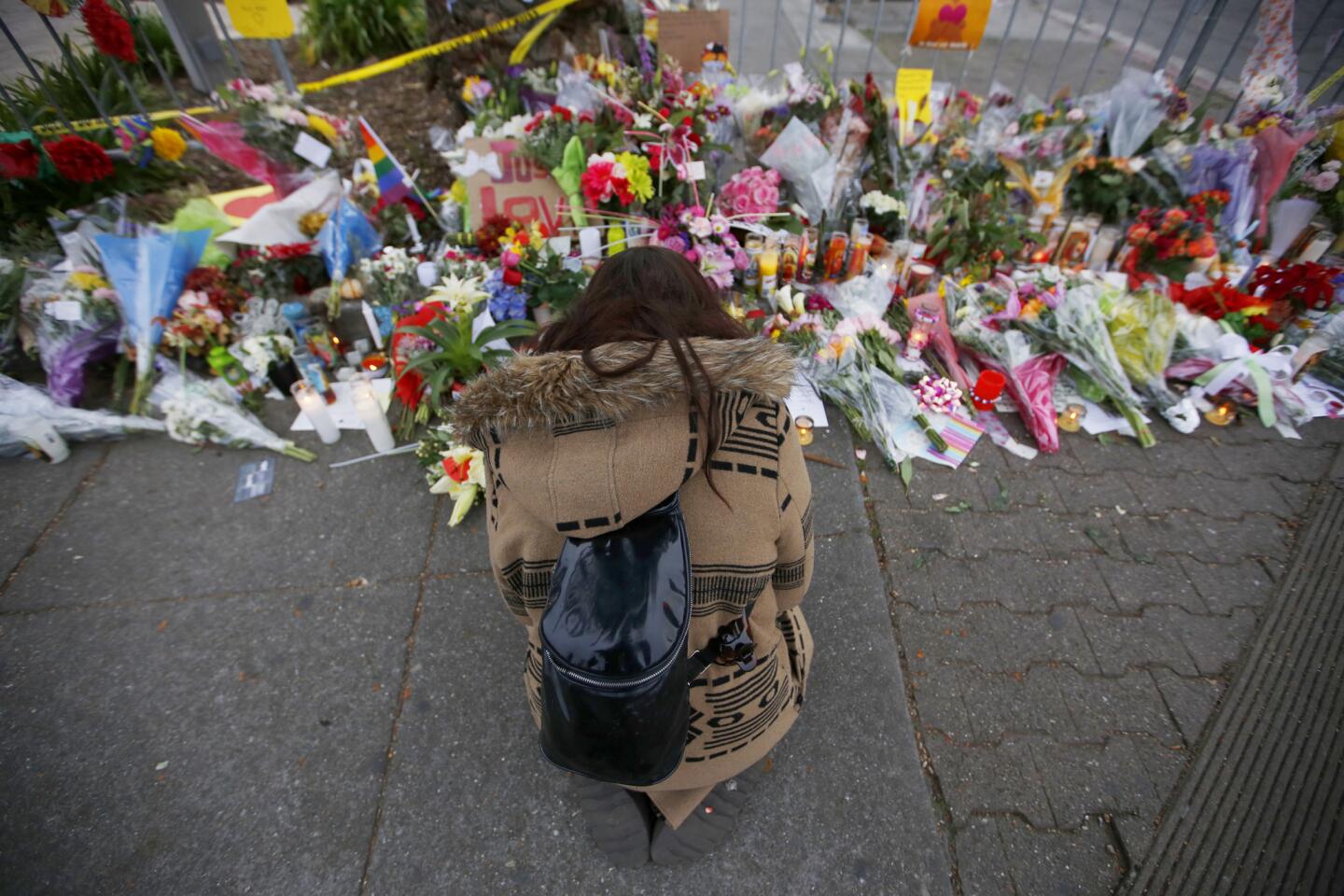

Reporting from Oakland — On Monday, three days after 36 people died in a fire at an Oakland warehouse, city building code inspectors sprang into action.

They descended on five other warehouses that authorities suspect are housing people illegally. Some of the properties, like the one gutted during a Friday night concert, had been the subject of complaints about building and safety code violations. None are permitted for residential living.

By Thursday, one of those properties had been cited, and inspectors planned to return to the other warehouses, public records reviewed by The Times show.

The inspections follow the growing scrutiny Oakland officials are facing over what many consider an inadequate response to safety concerns at the Ghost Ship warehouse, the scene of the deadliest fire in modern California history.

These questions were heightened when officials revealed that no building code enforcement inspector has been inside the warehouse in at least 30 years despite the fact that, according the city records, the building and its adjoining lot had been the focus of nearly two dozen building code complaints or other city actions.

Moreover, a source in city government said Thursday that the address for the warehouse was not listed in the Oakland Fire Department’s database of buildings requiring inspections, raising questions about whether that agency examined the Ghost Ship.

The city’s Fire Prevention Bureau is required to conduct annual inspections of all commercial buildings and multi-family residences, according to city ordinance. Officials have yet to release any fire inspection reports regarding the warehouse.

Mayor Libby Schaaf vowed to strengthen Oakland’s building and fire inspection programs and to crack down on code violations, but said the city would not conduct “witch hunts” against its employees or agencies responsible for investigating building and safety complaints.

“I want to be clear we will not scapegoat city employees in the wake of this disaster,” Schaaf told reporters Wednesday. “Rather, we will provide them the guidance, clarity and support they need and deserve to do their jobs.”

The interim director of the city’s Planning and Building Department said the agency’s building code inspectors go into buildings only when the owner seeks a permit or if officials receive a complaint. The city, which is home to more than 400,000 people, has 11 building code enforcement inspectors, director Darin Ranelletti said.

Over the past three years, the department investigated at least three of the complaints at the Ghost Ship warehouse that appeared to assert that structures had been built inside without permits or that the property was being used as a residence. Most of the other complaints cited illegal parking and mounds of debris piled up on the sidewalk and in an adjoining vacant lot.

A building code inspector visited the warehouse 15 days before the fire to investigate complaints of trash and debris piled outside and an “illegal interior building structure.” But the inspector was unable to get inside, triggering questions about whether a more aggressive investigation would have identified the multiple building code violations inside the structure — including unpermitted electrical work, makeshift residences and a staircase made partially of pallets — and possibly prevented the tragedy.

Planning and Building Department reports released Wednesday indicate that on Nov. 21 the city sent a violation notice to the property owner demanding that debris outside the building be cleaned up, but the notice did not request access inside the warehouse.

The city’s top building official also appears to have changed his story about the details of that investigation. Ranelletti told reporters Wednesday that the inspector was trying to enter a fenced lot next to the building, not the warehouse itself. The warehouse and lot are separate parcels, but they are adjoined and owned by the same person.

Ranelletti provided a different version of events at a news conference the day after the fire, saying, “We had an inspector attempt to enter the building and at that time was not able to secure access to the building.”

City spokeswoman Karen Boyd explained the discrepancy Thursday.

“It wasn’t clear until later that there were two properties and that the inspector’s inability to gain access referred to the lot, not the warehouse building,” she said.

Questions about the competence of Oakland’s building inspection agency arose five years ago. An Alameda County Grand Jury in 2011 released a scathing report accusing the city’s building services division of mismanagement and having haphazard policies about conducting building inspections.

The grand jury found that agency was riddled with “poor management, lack of leadership, and ambiguous policies and procedures.” It added that the agency had inconsistent standards on code violations and that the violation notices sent to property owners were late and hard to understand. In addition, inspectors treated property owners in an “unprofessional, retaliatory and intimidating” manner.

Schaaf, who was a city councilwoman at the time of that report, said many of those concerns were quickly addressed, and she noted that the city also has been criticized in the past for being too aggressive with building code inspections.

The Ghost Ship warehouse was owned by Oakland resident Chor N. Ng’s trust and zoned exclusively for commercial use. It housed an artists collective and, according to former residents and those who frequented the building, had unpermitted living quarters inside and hosted concerts and other events.

The catastrophic fire appears to have triggered a wave of warehouse inspections by Oakland code enforcers.

Inspectors were sent to the addresses of five warehouses allegedly used as alternative housing. Most of the properties had records of past complaints that included blighted conditions, unpermitted work and illegal squatting.

By Thursday, public records show, one of those properties had been cited for unspecified violations. The other buildings include a 6,600-square-foot warehouse on Oakland’s west end industrial center that local residents call “Death Trap” — a label they said a city inspector used when inside the building in 2011.

The records show the Magnolia Street property, built in 1925 and zoned for industrial use, was the subject of repeated complaints and investigations in 2011. It had alleged alterations without permits, graffiti, trash and debris and “substandard” housing. The case regarding the blight complaints was closed in September 2011 when the property was cleaned up. However, a housing habitability complaint remained open until January 2014 when it was closed as “unable to verify.”

The city’s planning and building department only goes into buildings when the owner seeks a permit or if officials receive a complaint.

A new inspection was conducted Thursday after the city Fire Department filed a complaint.

Oakland records show another warehouse blocks away also was listed for inspection Monday. On Wednesday the 1,000-square-foot building, a single-story green structure built in 1930, was found in violation of housing codes. A violation notice was mailed to the owner on Thursday.

The property, last zoned to house a hydroponics office, was cited twice in 2015 for illegal habitation, including a complaint of “20 squatters occupying the site.”

ALSO

L.A. plans crackdown on unsafe warehouses in wake of Oakland tragedy

In diverse California, a young white supremacist seeks to convert fellow college students

Star Wars X-Wing fighter parked on Hollywood Boulevard, but no cars allowed

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.