Teachers told their students everything would be OK after the election. Now, they’re not so sure

- Share via

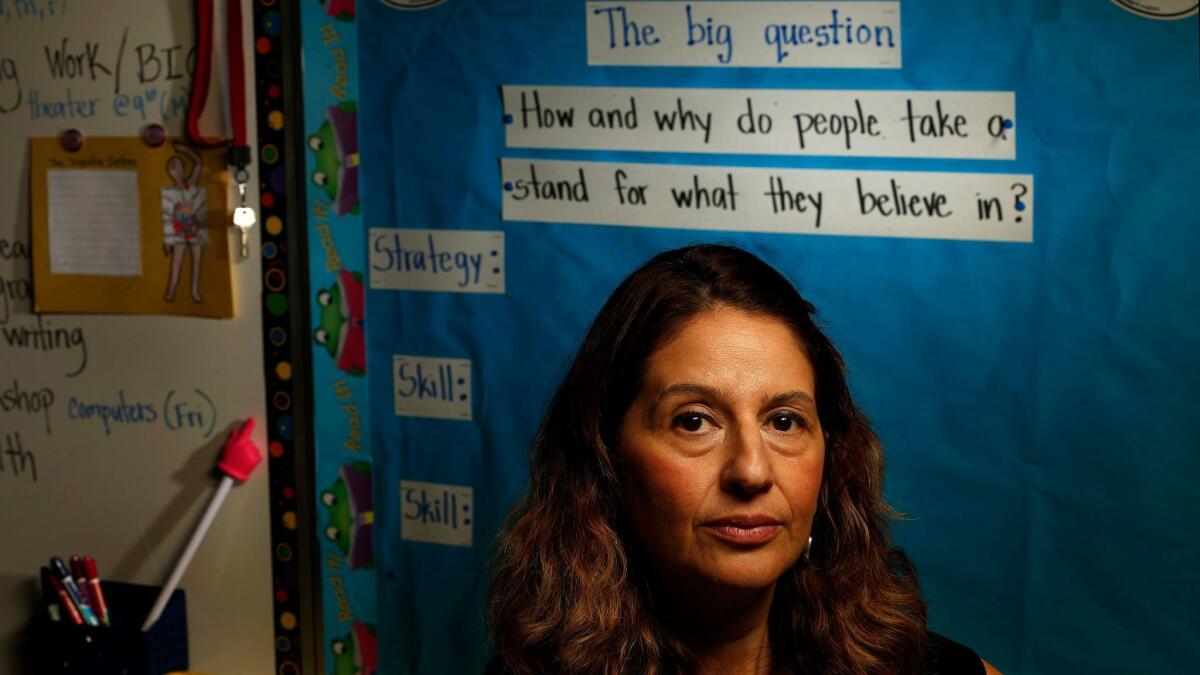

For months leading up to the presidential election, elementary school teacher Ingrid Villeda tried to instill in her students a certain faith in democracy.

The 18-year veteran of L.A. Unified’s schools looked for simple ways to decode the ugly back-and-forths on TV. She taught her fifth-graders about the virtues of a democratic nation in which ordinary citizens study the candidates’ policy positions and then choose their leaders. She wore suffragette white on election day and told them the story of how women fought for and won the right to vote.

Within the walls of Villeda’s school, 93rd Street Elementary, where roughly three-quarters of the students are Latino, Donald J. Trump and his vow to deport millions of immigrants living in the country illegally seemed far away and fictional. That is, until the morning after the election, when Villeda’s students ran to her in the schoolyard, the sleepless night written on their faces.

“People really don’t like us?” asked a girl from Mexico. “What are we going to do about that?”

Recalling this moment in a phone conversation, Villeda began to cry. “They’re looking at me to be able to stand in front of them and say, ‘You’re OK; we’re going to be fine.’ ”

For students and teachers in the nation’s second-largest school system, the repercussions of America’s choice for president are likely to be both profound and lasting. In L.A. Unified, 74% of the roughly 600,000 students are Latino, and many have relatives and acquaintances who are living in the U.S. without legal permission.

Children are coming to school shrouded in anxiety, asking teachers to interpret the day’s headlines for them, examining each bit of news for its potential threat.

“Am I safe?” many want to know, voicing new concerns about immigration raids or hate-inspired attacks against religious and ethnic minorities as well as LGBT people.

“All week long they’ve been kind of like zombies, numb from shock, and so have a lot of educators,” said Martha Infante, 46, a social-studies teacher at Los Angeles Academy Middle School. The day after the election, she said, was the most difficult day of her career.

During lunch and after school, students gathered in Infante’s classroom to ask her questions, many of them newly curious about the inner workings of American government. “How soon can the deportations start?” one asked. Trying to assuage their anxieties, Infante explained the system of checks and balances and assured them that no one person can make law in the U.S.

“Their fear is palpable,” she said. “We are going to need to revisit these issues, because I only see the fear getting greater, and the students will not be able to learn if fear is foremost in their minds.”

Among high school students, there have been shows of defiance. Hundreds have participated in walkouts and protests, prompting district Supt. Michelle King to send a robocall to parents Monday morning, asking them to keep their children in school.

“It is also critical that students not allow their sentiments to derail their education,” King said in the message.

The morning after the election, James A. Garfield High School social-studies teacher Erica Huerta gathered her students in a circle to discuss the election and what role they could play in shaping the country’s future. Out came a torrent of questions about immigration, climate change, and rights for gay and transgender Americans. One student wanted to know: What are the steps to impeach a president?

Several students who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children broke down crying, Huerta, 39, said. One girl, a junior with excellent grades, said, “I don’t know what my future holds anymore.” Another one of Garfield’s top students, who is also in the country illegally, didn’t come to school at all.

She doesn’t know if she’s going to be applying for college anymore. She doesn’t know if she’ll be able to stay in the country.

— Erica Huerta, social-studies teacher, about one of her students

“She doesn’t know if she’s going to be applying for college anymore,” Huerta said. “She doesn’t know if she’ll be able to stay in the country.”

Teachers said they are worried that the haze that seemed to settle over the nation postelection will not be so easy to clear from schools. Their students are listening to the news while they do their homework, absorbing fear and a sense of being under siege from their families, and they are bringing all of it to the schoolhouse door each day.

Villeda said that when her fifth-graders ask her if they are safe, she tells them they are lucky to live in California, where many elected officials, including some in Los Angeles, have declared their resolve to protect immigrants. She worries about keeping her students motivated, particularly those with temporary resident status.

“The school board members keep saying, ‘We want all the kids to graduate, we want all the kids to graduate,’ ” she said. “But how do you encourage kids to continue to dream?”

The Board of Education has promised to protect students’ immigration information and shield students from deportation whenever possible.

Some teachers said the current mood in schools reminded them of the controversy that surrounded Proposition 187, a ballot measure approved by California voters 22 years ago that denied public services, such as public education and healthcare, to people in the U.S. without legal permission. Although most of the law was struck down in court, it prompted schools across L.A. Unified to hold workshops and offer families advice on how to prepare their children in case they were seized by immigration agents.

Since the election, some teachers have talked about reviving those meetings. They worry that many students raised in an age of ubiquitous cellphones haven’t memorized the phone numbers of the relatives and neighbors they would need to call if their parents were detained.

Others said they will no longer encourage students to apply for President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, an initiative that has shielded thousands of young people from deportation and allowed them to work in the U.S.

Although this once seemed a fail-safe way to protect their students, the program now is threatened, and some fear its records could be used to identify people for deportation.

“There’s just a sense of guilt on our part as educators. We told these kids they could get permission to work legally, and they could go to college,” Huerta said. “What do we tell them now? What dangers have we unknowingly put them in?”

Twitter: @annamphillips

ALSO

At UC regents meeting, unease and uncertainty over Donald Trump’s presidency

Cal State will not help deport undocumented students under Trump, chancellor says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.