Great Read: With weight-loss competition, sheriff’s officials strive to regain top form

- Share via

As a new sheriff’s deputy, Michael Tadrous was 200 pounds of muscle.

Then his eating habits caught up to him. At parties, he scarfed 40 stuffed grape leaves. At work, he downed chicken sandwiches, fries, Cokes.

Fifteen years later, he weighed 278 pounds, which at 5 feet 8 made him morbidly obese and pre-diabetic.

The extra weight made him feel like a truck dragging a heavy load. He had recently loosened his gun belt yet another notch, and his pants were size 44, up from 37 as a rookie.

On patrol duty in Pico Rivera, he might find himself chasing a suspect or wrestling someone to the ground — and coming out on the losing end.

He was ready to make a change. One morning in August, Tadrous stood outside Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department headquarters in his tan-and-olive uniform with co-workers who would diet for the next 10 weeks in the law enforcement version of “The Biggest Loser” weight-loss contest.

One woman, a deputy at the Pasadena courthouse, said her pants had split open while she was frisking a defendant. Another, a sergeant in Lancaster, said she didn’t want to be a laughingstock to her daughter after nearly getting stuck on a slide at a water park.

Most of the 45 sheriff’s employees were obese and aiming to shed 25, 35, 50 pounds. Tadrous’ goal: 70 pounds.

He had lost weight before and gained it back. This would be the last time, he promised. He wanted to set a good example for his three young children — and to be around to watch them grow up.

“I love food,” said Tadrous, 37, “but I love life a little more.”

::

New deputies emerge from the Sheriff’s Academy in the best shape of their lives.

They have been through four months of boot camp-like exercises. They have passed physical fitness tests and a background check. They must meet a weight requirement for their height. A 5-foot-10 man, for example, can weigh no more than 185 pounds or have no more than 22% body fat. Only one in 100 applicants makes it through the process.

Then the years and the pounds accumulate. The doughnut shop stereotype is partly true — patrol deputies say they resort to bolting down fast food because they have little time to eat. There are no more fitness tests or weigh-ins to keep them in line.

By the time some progress from slim to extra large, they have been promoted to a higher rank and a desk job. Others remain on street patrol or supervise felons in the jails — jobs where being a step or two slower could be costly.

In the Army, soldiers step on the scales every six months and are promptly enrolled in a weight-loss program if they’re too heavy. But most local law enforcement agencies don’t monitor their officers’ weight.

“Some employees, you see them in their physical condition, and it’s a concern,” said LAPD Cmdr. Andrew Smith, who has been the same rail-thin 6 feet 1 and 170 pounds for his entire 26-year career. “It doesn’t appear they can perform the functions of a police officer.”

At Goodie’s in Norwalk, which stocks uniforms for the Sheriff’s Department, the pants on the shelves go up to size 50. In the storeroom, owner Jim Wadley keeps larger ones, requested by customers on occasion. On a recent day, he pulled out a size 60, the expanse of olive-colored cloth large enough to enclose two normal-weight people.

“The overweightness in the department — or if you want to say obesity — is probably 10%,” Wadley said. “After the academy, they gain.”

Todd Rogers, the assistant sheriff overseeing recruitment and training, said he would award a financial bonus for physical fitness — if he had the funding.

Rogers runs four miles or lifts weights every morning to keep in shape for a foot pursuit, though as a top official he is unlikely to encounter one.

Jeffrey Steck, head of the deputies’ union, supports a fitness bonus coupled with time to exercise while on duty. Fewer deputies would be injured on the job, and fewer would die of heart attacks, he said.

“We need to be in great shape to do our job, and we put ourselves at risk when we’re not in great shape,” Steck said.

::

The call came over the radio — a burglary suspect was on the loose. Tadrous flicked his siren on and floored the accelerator as his partner, Mike Barraza, called out directions.

In a residential Pico Rivera neighborhood, four other deputies had already caught a young man in a gray sweatshirt and long gray shorts. His loot — gold watch, gold chain, pearl brooch — was spread on the trunk of a patrol car.

Barraza scaled a concrete wall into an adjoining backyard to check for more suspects. Tadrous hung back — there were enough deputies on the other side, he said.

“I could have jumped it, guys. I just chose not to,” he said in response to teasing about his weight.

After four weeks, Tadrous had lost 27 pounds. At family gatherings, he resisted the shrimp and the chips and salsa, settling for a veggie sloppy Joe and a protein bar. His olive pants, down to a size 40, were baggy, and he repeatedly hitched them up.

At a 7-Eleven after the burglary call, Tadrous bought a Super Big Gulp Diet Coke — an addiction he was trying to kick. In the parking lot, he produced a hard-boiled egg from a blue cooler in the trunk, handing the yolk to Barraza, who was about the same height as Tadrous but 60 pounds lighter. Tadrous wolfed down the egg white on a slice of wheat bread before heading out on the next call.

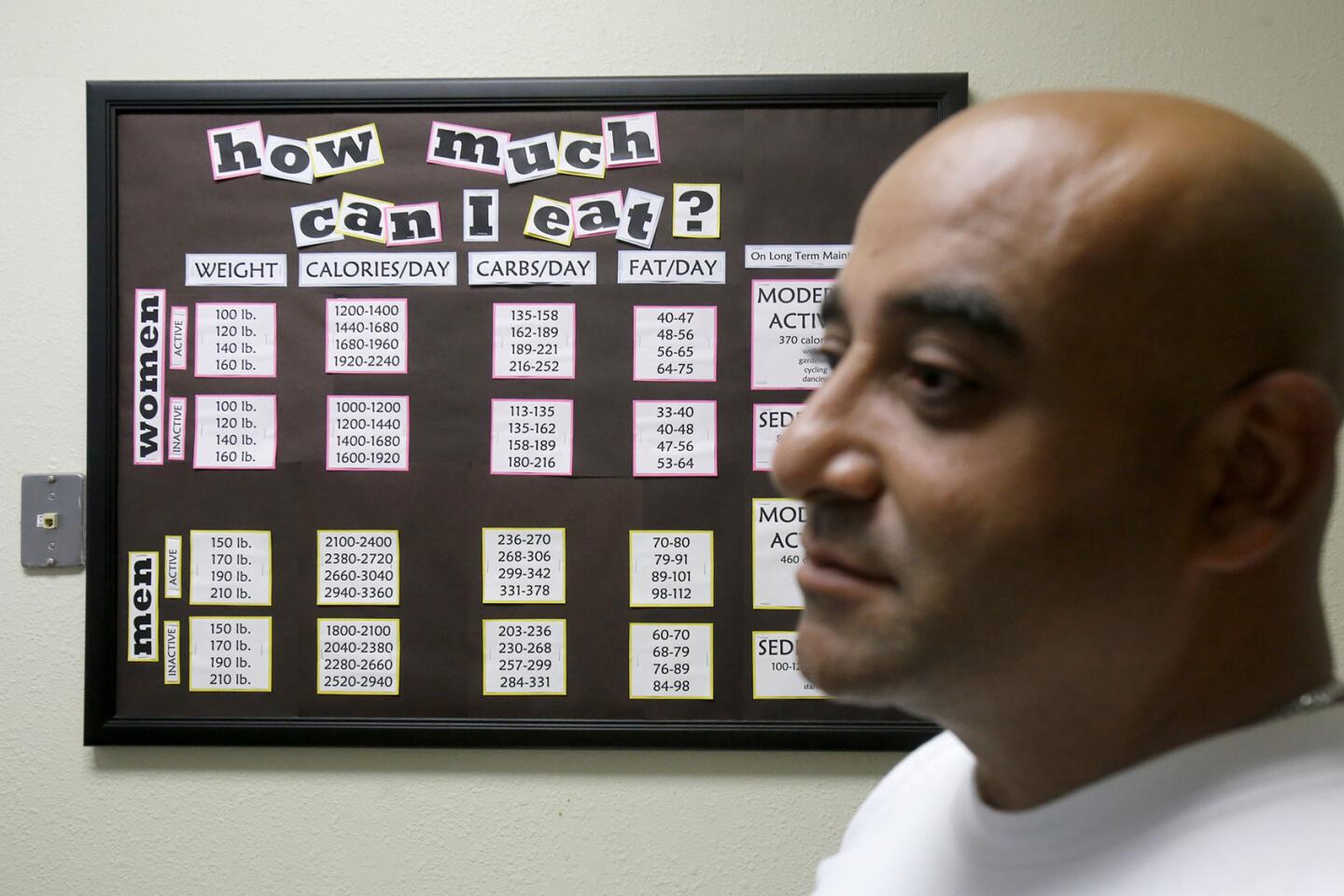

In addition to the low-carb, small-portion diet prescribed by Lindora, the company that sponsored the weight-loss competition, Tadrous’ regimen included daily visits to a clinic to be weighed and counseled.

After dealing with a belligerent woman in a McDonald’s and then an elderly man with dementia, the deputies stopped for a late lunch at Zankou Chicken. Tadrous, who was born in Egypt, greeted the owner in Arabic.

Once, Tadrous would have had two or three pita breads, hummus, tahini and four garlic sauces with his meal. On this day, he stuck to grilled meat and salad, refusing when Barraza offered him some baklava.

“It’s so good but off-limits,” he said.

::

After 10 weeks of self-denial, the contestants were back at Sheriff’s Department headquarters on Nov. 12, holding “before” photographs in front of them.

On cue they let go, the cardboard images of their larger selves clattering to the ground.

Tadrous was down 46 pounds and just 2 inches away from fitting into the size 37 pants he had worn as a rookie.

Others had lost even more, putting Tadrous out of the running for an award. Christopher Germann, a sergeant in the scientific services bureau, had shed 67 pounds. Sheila Finley, who works in the jails, had lost 51 pounds.

Over 70% of the contestants, who included both sworn and civilian employees, had lost at least 20 pounds.

Tadrous was short of his 70-pound goal and still in the “obese” category, so he had enrolled in another Lindora plan.

Already, his repertoire of self-deprecating fat jokes — “I want to be half the man I used to be” — was starting to seem obsolete.

Horsing around with his children — a 10-year-old girl and two rambunctious little boys — was much easier now, Tadrous said. He could run up a staircase; he had once struggled even on the way down. He could get out of his patrol car more quickly. And he was sure he could scale that wall with ease.

“Everything is about officer safety,” he said. “Every second counts.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.