It’s about quality, not quantity, when it comes to child literacy

- Share via

America’s doctors have joined the chorus urging parents to read daily to their children, instead of handing over iPads or parking the kids in front of the TV.

The American Academy of Pediatrics launched its “literacy promotion” campaign this week, citing the influence of early literary experience on children’s brain development and their ultimate academic success.

The initiative raises the bar for both parents and doctors: Parents should read aloud to their children every day, from infancy until at least kindergarten. Pediatricians should talk about reading at every checkup, and hand out age-appropriate books to low-income patients.

I’m hardly one to argue against the value of reading, but I find that overly prescriptive. Pediatricians already have plenty to attend to. And trying to get a 6-week-old to pay attention to “Goodnight Moon” seems likely to make new moms and dads feel like failures at the starting line of a parenting marathon.

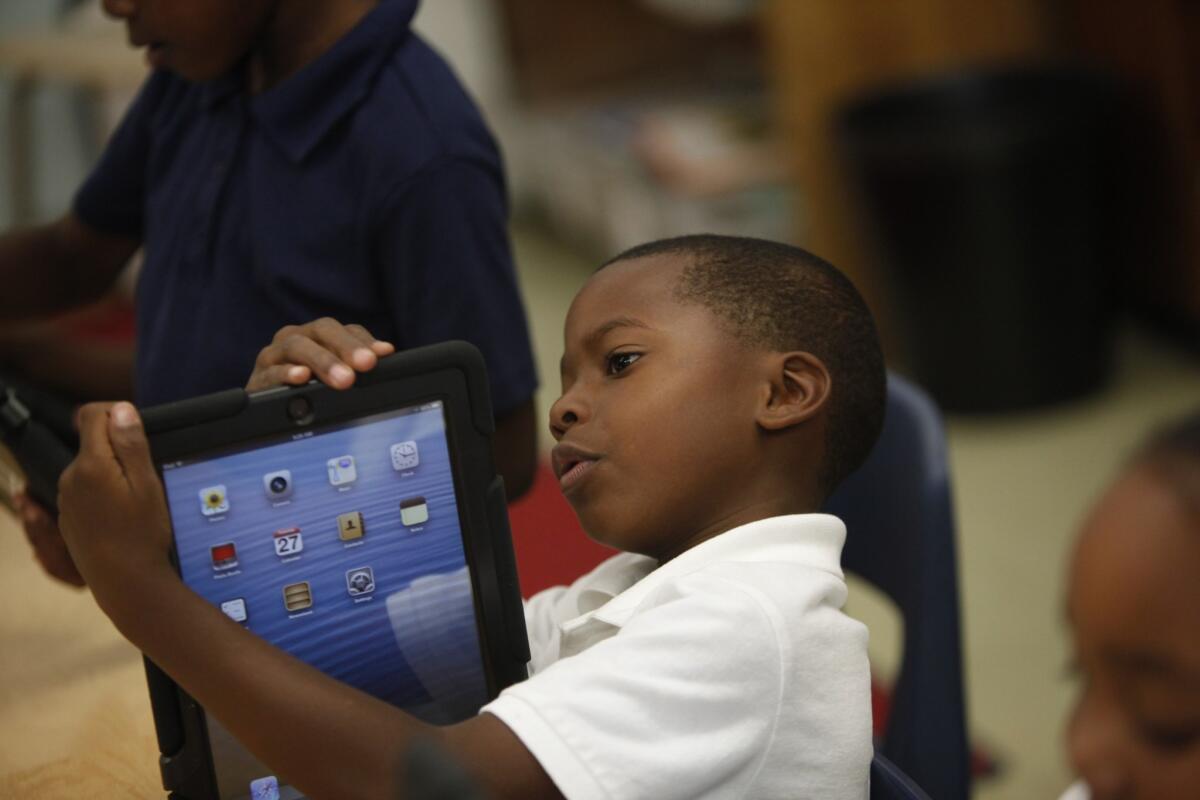

Yet the campaign’s aim is vitally important. I hope it jumpstarts a public conversation about the value of parenting basics often overlooked in a world of high-tech tools — where schools hand out tablets instead of books to first-graders, and toddlers learn to swipe the screen of an iPhone before they learn to turn the pages of a book.

::

The new policy is already generating blow-back from parents online.

Some want pediatricians to stick to health issues and leave the cognitive stuff to experts. Others worry that a lecture might shame or run off parents who are poor readers. Many think it’s too simplistic to focus on reading as the single route to better language skills.

It’s true there’s nothing magic about the act of reading aloud. You can’t inoculate a child against academic failure with a nightly dose of “Where the Wild Things Are.”

But the process and the ritual are important in ways that transcend intellectual gains or school test scores. The snuggling, the bonding, the shared delight in a toddler’s discovery of textures, ideas, sights and sounds can be the building blocks of a strong foundation between parent and child.

Still, daily reading sessions — even if they begin with newborns, as the doctors’ group suggests — won’t remedy the early language deficits that hobble our education system and sabotage millions of children.

One in- three American children begin kindergarten without the basic language skills they need to learn to read. Among low-income students, 80% are not proficient readers by the end of third grade — a milestone that’s considered to be the best predictor of high school graduation rates.

Those troubling stats have fueled a national push for universal preschool. Well-trained teachers and enrichment tools can compensate for the deficiencies of low-income families, the thinking goes.

But that doesn’t address a deeper issue, with cultural, economic and generational roots:

Parents may need to fundamentally change the way they talk to their children at home if they want them to succeed in school.

::

Thirty million words. That’s the shorthand way experts describe the literacy gap between rich and poor kids.

It’s based on a landmark study suggesting that by age 3, the children of affluent parents have been exposed to 30 million more words than children in low-income families.

The well-educated parents talked with each other and their children more — praising, encouraging, correcting, explaining, asking questions and offering choices. Their children heard about 2,150 words an hour at home.

The children of working-class families heard an average of 1,251 words every hour; children on welfare heard just a paltry 616.

And the tone of conversation in low-income homes was apt to be harsh. High-income parents praised their children six times as often as they delivered prohibitions. Children from families on welfare received two “discouragements” for every encouragement, the study found.

Researchers tracked those children for years and found profound impacts on academic performance linked to parents’ communication styles. That’s been used by some to explain our nation’s persistent socioeconomic achievement gap in education.

But Stanford psychologist Anne Fernald found that the differences are not just economic. She studied low-income toddlers in Northern California and found wide variations in the number of words spoken to them in a day — from 670 to 12,000.

The more words they’d heard by 18 months, the better they were at processing language — following directions, learning new words, labeling items and making choices.

That was a revelation to their mothers, Fernald said. And it points to the missing piece — educating parents — in the puzzle of how best to promote children’s academic success.

“The style of talk in a family is pretty deeply entrenched,” Fernald said. “It’s challenging to change because it’s not one thing but a thousand things every day.”

But parents are receptive, she said, once they understand how important it is to make their children “conversational partners” and not just little people to ignore or order around.

“It’s not about telling [parents] ‘Do this. Don’t do that’,” she said. “It’s about changing how you interact with a child — whether you perceive a question as a threat to your authority or the leading edge of curiosity that will serve this child well in school.”

What matters most is not quantity — how many words you say or the number of books you read to your children — but the quality of the conversation, according to Fernald.

That means taking the perspective of the child, she said, paying attention, building on their interests, encouraging more than you scold.

And asking yourself whether that sassy little 5-year-old with an opinion on everything is a mouthy brat or an imp with a healthy sense of his or her own intelligence.

Twitter: @SandyBanksLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.