Buddhist Meditation Center rises in Adelanto

- Share via

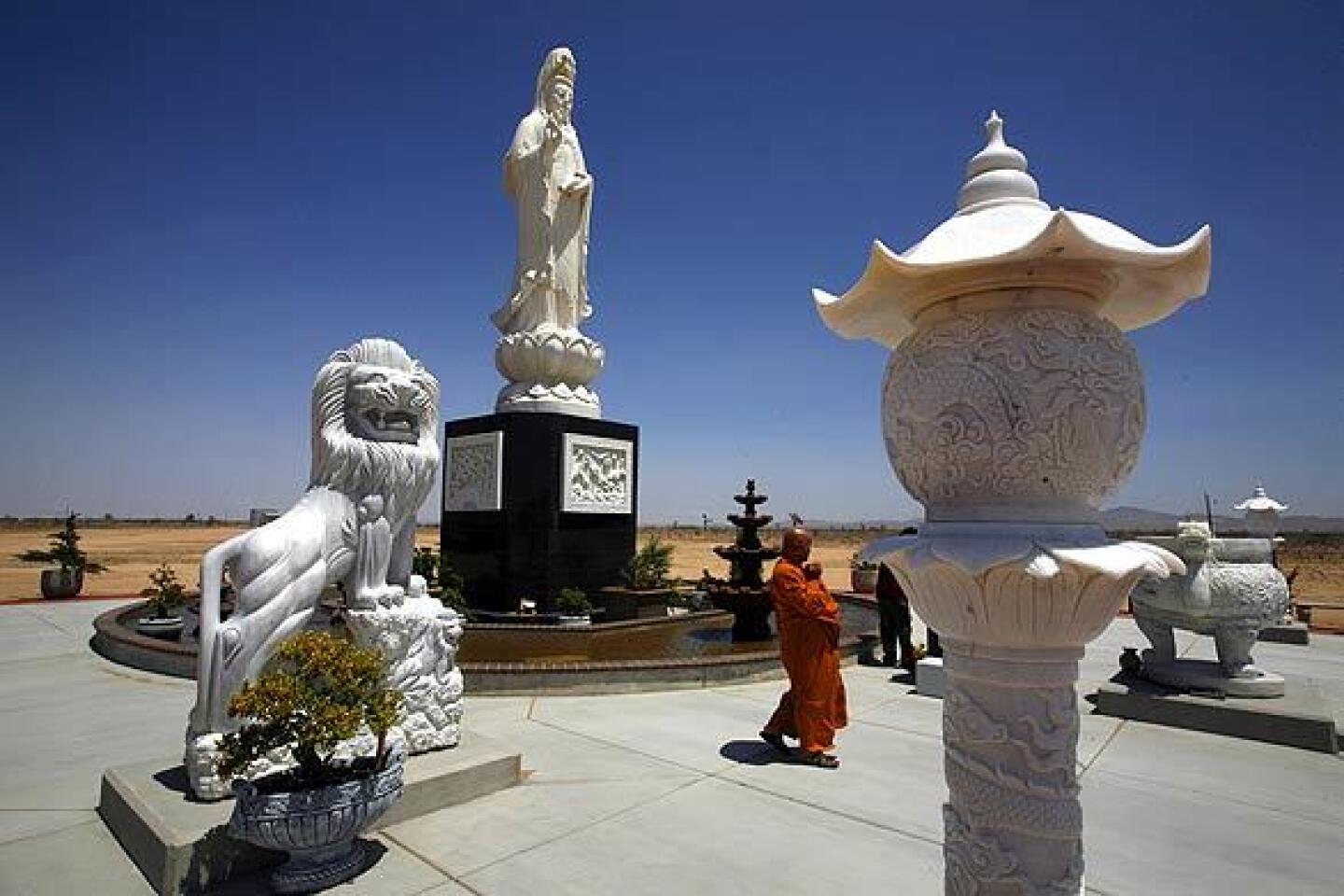

ADELANTO, CALIF. — It doesn’t take long to get acquainted with the rhythm of things at a new Buddhist shrine in this high-desert community presided over by a monk nicknamed “Tom” and a 24-foot-tall statue of a saint said to have miraculous powers.

Monk Thich Dang “Tom” Phap’s routine starts with early morning meditation and yard work. When 11 a.m. rolls around, there he is, sandal-shod and in orange robes, a gold shoulder clasp gleaming in the desert sun as he stands in prayer before the 60-ton white marble statue of Quan yin.

After lunch, he whacks weeds, washes the statue and naps. In the late afternoon, he has a dinner of soup and rice followed by meditation and prayer. At 9 p.m., Phap calls it a day.

“I pray for Quan yin to help everyone else in the world,” said the 67-year-old monk, who lives in a modest trailer beside the statue. “Then I pray she helps me.”

Reverently admiring the statue -- serene of face, with half-closed eyes and flowing robes -- he added in broken English, “Soon we will have grass and flowers and air-conditioning. This I believe. Yes!”

In his faith’s pantheon of bodhisattvas -- not gods but enlightened people a step below buddhahood in perfection -- Quan yin is among the most popular, and powerful.

Over the centuries, Quan yin has become many things to many people. The saint has lost masculine attributes and gained feminine ones in their place. In some woodblock prints and statues, she appears with many eyes and arms.

“She has a thousand eyes with which to see those who suffer,” Phap said, “and a thousand arms to reach out and help them.”

In Japan, she is known as Kannon. Elsewhere, the devout know her as Avalokitesvara. In China, she is Quan yin. But in South Vietnam, where Phap grew up, she is Quan The Am, the personification of compassion and the inner transformation necessary for redemption.

Phap refers to her by her most common name, Quan yin.

Phap said he searched far and wide for a site on which to place the statue donated by a wealthy businessman in Malaysia. He bought the 15-acre lot in Adelanto about four years ago.

“It was suitably tranquil,” he said of the barren spot just east of U.S. 395 and about 10 miles northwest of Victorville.

For local concrete contractor Gary Lucas, Quan yin and the wind-swept desert she towers above remain works in progress. “The competition didn’t want to touch this job,” he recalled. “They looked at the blueprints and said, ‘We’ll get back to you.’ ”

“It was the toughest contract I ever tackled,” he added. “We lifted the statue up onto the pedestal in September with a 70-ton crane. The wind was blowing hard that day and kicking up dust -- took nine hours to stand her up.”

A week ago, Lucas’ crews were putting final touches on a 465-foot-long concrete walkway leading to the statue and a reflecting pool beneath its feet. Sometime next month, the walkway will be lined with vases of flowers and statues of Buddhist saints.

“That will complete Phase One,” Phap said. “If all goes according to plan, we’ll start construction of a 6,000-square-foot meditation hall in June.”

Even some of Phap’s followers called that timeline optimistic, given that the project -- called the Buddhist Meditation Center -- is being funded by donations.

“We build what we can afford,” Phap said. “Right now, we have about $400,000. We need $12 million. But I have faith. Yes!”

Phap, whose secular name is Thao Nguyen, was raised by devout Buddhist parents, according to his son, Peter Nguyen, 35, the eldest of four children. Phap served in the South Vietnamese military during the Vietnam War and immigrated to the United States in 1979.

He entered Dai Dang Monastery and meditation center in San Diego about seven years ago. After his ordination, following tradition, he left his worldly belongings behind to practice and teach Buddhism.

Now, even his children refer to Phap as “venerable monk.”

“I’m impressed by his visions, enthusiasm and energy,” said Nguyen, who owns a medical supplies business in Orange County. “A few years ago, I asked him, ‘Venerable monk, why are you doing this at your age? You are not a young man anymore. Why must you have so much ambition at your age?”

Nguyen’s father answered: “Have faith and it will be done.”

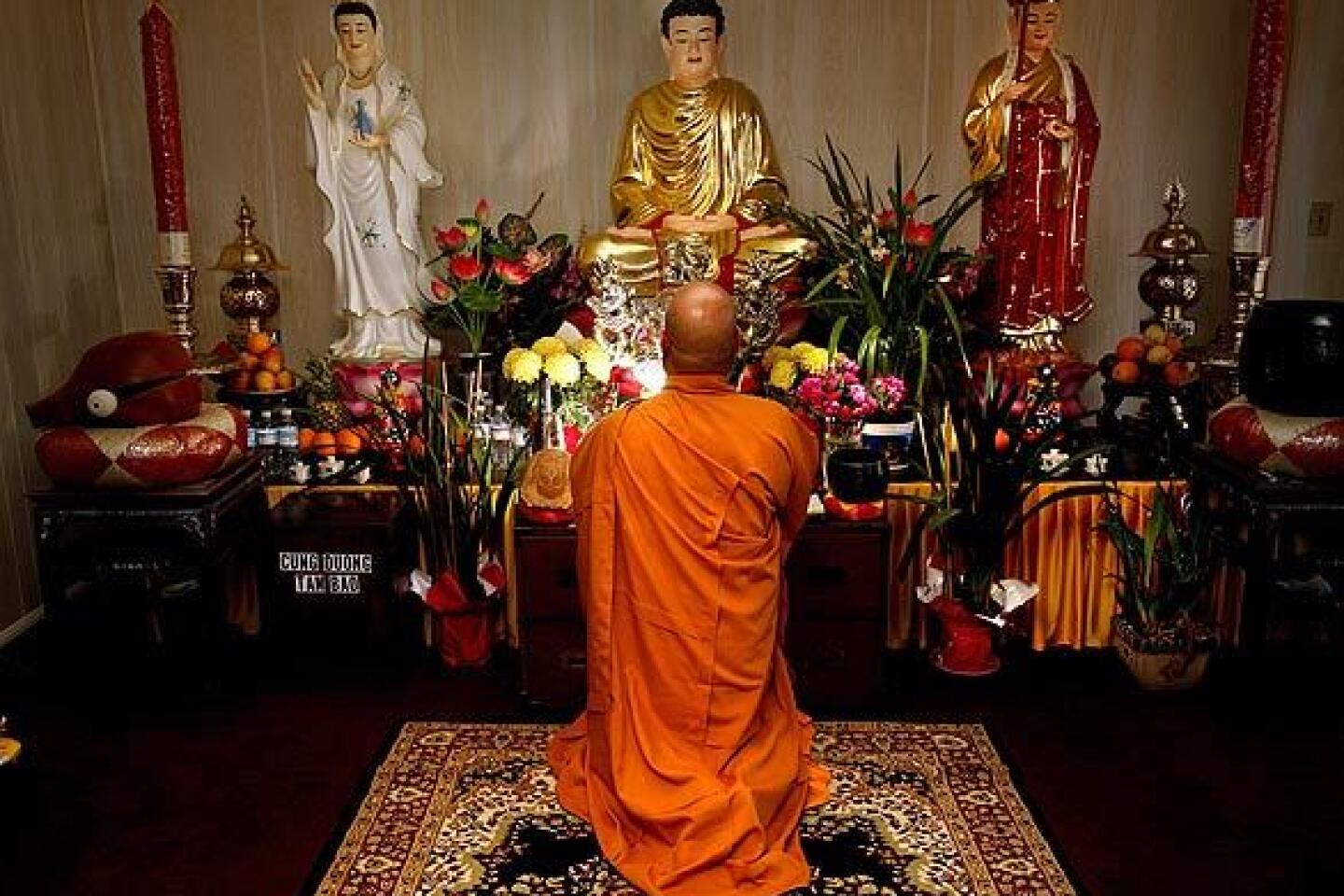

Phap spends much of his time in the trailer, which is filled with religious statues, scriptures, votive candles, vases of daisies and lilies, and tables laden with offerings of oranges and apples. In one room, he stores bottles of water donated by congregants who drive from as far as Santa Ana.

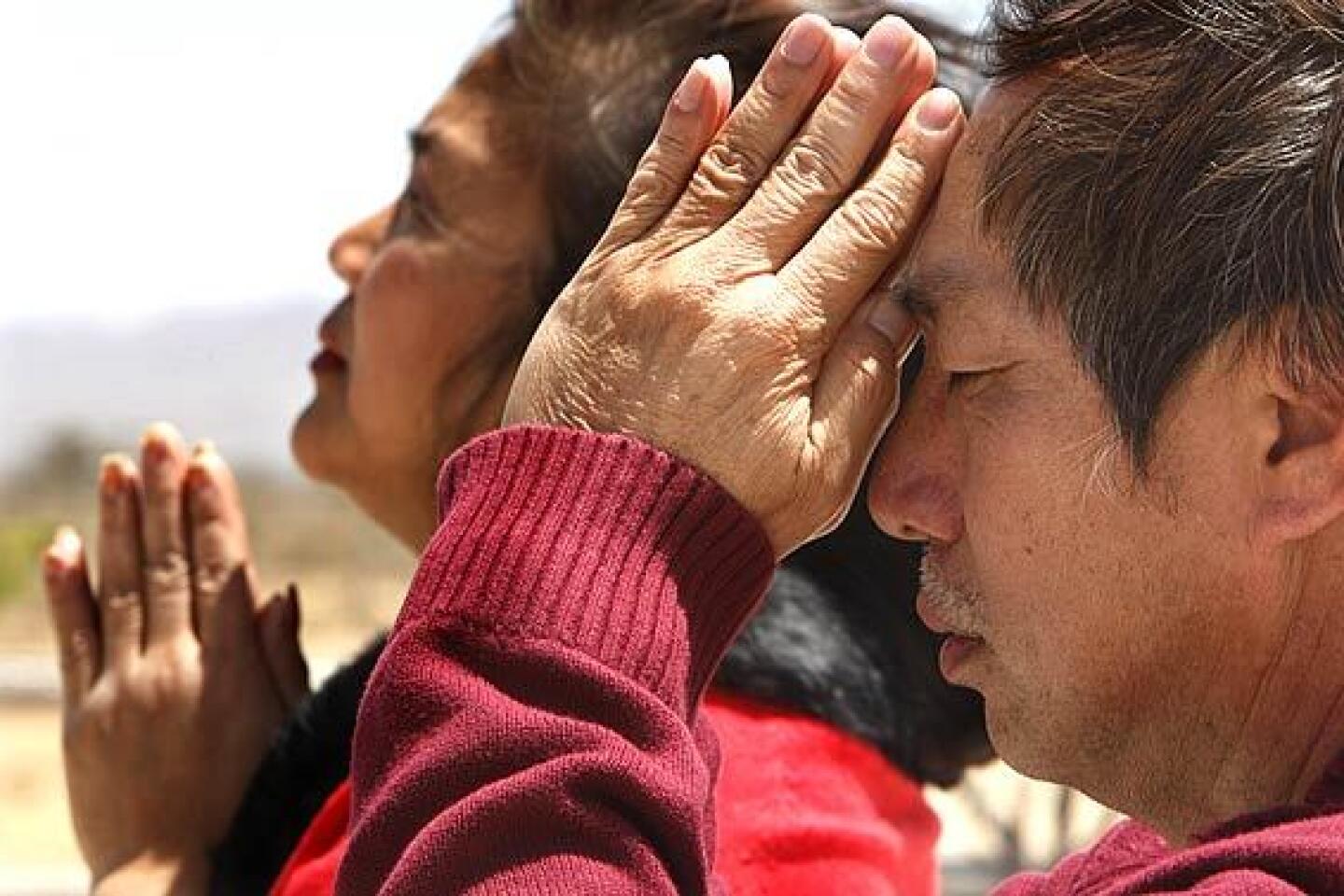

“Many people -- Chinese, Cambodian, Lao, Vietnamese, Americans -- come on weekends to pray for happiness and no stress,” Phap said.

Among them is Nguyen Huong, who has made the two-hour drive from her home in Westminster to the shrine at least once a week since November.

“I take my husband and cousins,” she said. “It’s a long and expensive trip. But Quan yin is very special, and Dang Phap -- he’s a good monk. I bring him food, water and fresh flowers.”

Phap said he only wishes he had more amenities to offer congregants. “There is much left to do,” he said, “but I am happy, healthy, strong and clear of mind.”

Then he laughed and said: “In the next reincarnation, I hope I will be born in the United States. I will be young and strong again and come back to this place and do a better job. This I believe. Yes!”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.