City Beat: Saul Isler’s 85 years read like a book: first the odyssey, now, the graduate

- Share via

Maybe you think you’ve got nothing left to learn. Maybe you think you’ve got it all figured out.

Saul Isler sees the unfolding of his stay on earth differently. He’s faced plenty of hardship over eight and a half decades. But through it all, he’s hungrily sponged up knowledge and tried to inch closer to getting what he wants most out of life.

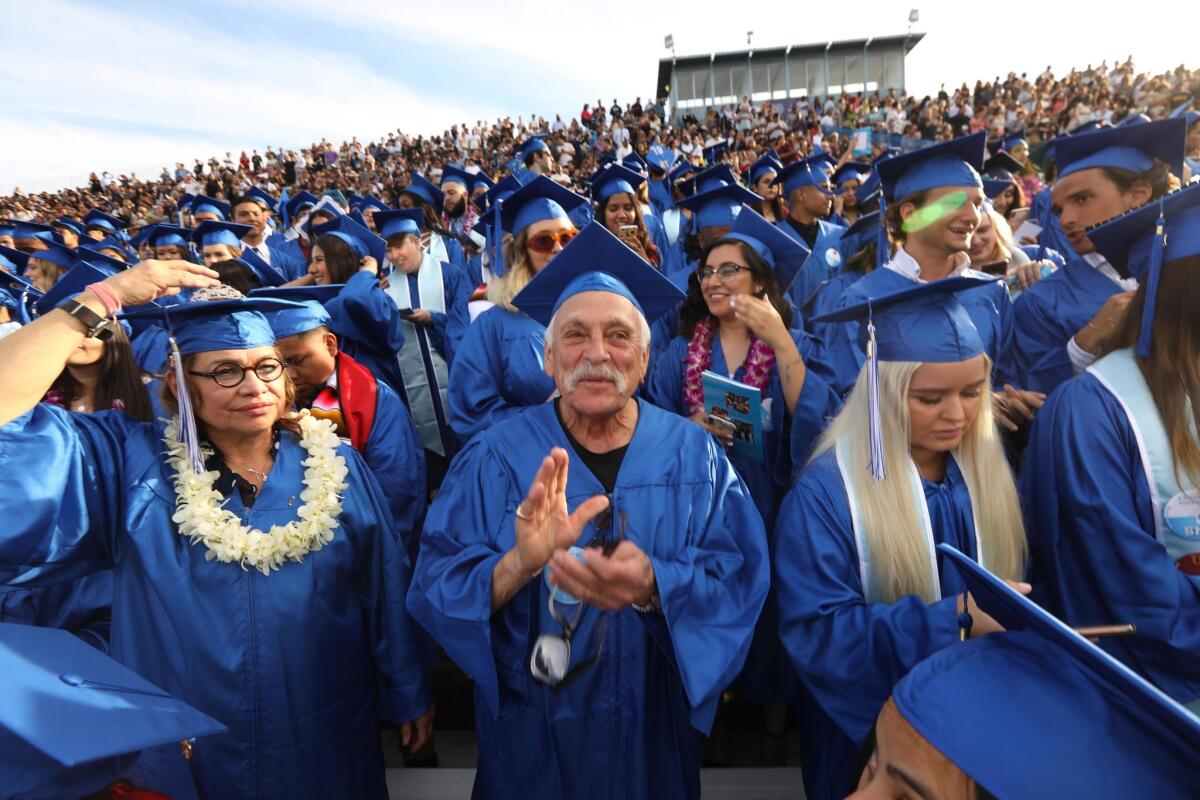

Cross one thing off the list: He just graduated from Santa Monica College, a week to the day after he turned 85.

He walked across the stage with hundreds of other grads, mostly born around the time when he might have retired, had he been the retiring sort.

When I launched my column, I asked you to share your L.A. experiences. Saul was among the first to reach out. He told me he was about to remedy his lifelong lack of degree “with cap, gown, pomp and circumstance,” and he invited me to come.

I wrote back that I wouldn’t miss it for the world.

What hooked me about his note? The very first words: “Nita: After flunking out of engineering school, I went on to become….”

I’m a sucker for a story about life’s twists and turns, especially if it involves a second or 10th chance. I also know about rocky college starts — though, luckily, a year off after freshman year focused my mind.

And I had a hunch — from how much I got out of my own, much shorter leave — that anyone who left higher education for 65 years, lived a full life and then came back to school was bound to have an illuminating perspective.

To earn a living, Saul had worked for an ad agency and then started his own. He’d had a thriving business as a patent draftsman, drawing by hand the kind of detailed, technical illustrations created today with computer-aided design.

For fun and pocket change, he’d written freelance newspaper articles, mostly about food. He’d done restaurant reviews on the radio and in print. He’d once had a column called “The Woodbutcher” about woodworking.

In recent decades, he’s produced three books of short stories and three novels — and he has more in the works. He’s also the author, as he wrote me, of “a treatise on the solving of acrostic puzzles” — another hook, I have to confess, for a committed crossword puzzler. (“If you get the hang of these, you’ll never go back to crosswords,” he tells me.)

Think of all that life experience entering a college classroom, as Saul did at 84. He walked into his first writing class and found a dozen young people playing with their phones in dead silence.

“I said, ‘Whoa everybody, my name is Saul and I want to know your names and why is nobody talking?’ And that began a relationship.”

Given the school’s thrilling diversity, so different from his earlier college days, he knew from the first day on campus that he wouldn’t really stand out, he said.

His may be an extreme case, but how many of us who went to college wish in retrospect that we could have waited until we were old enough to appreciate it more? How many of us also have bemoaned missed chances and, rather than bravely correcting course, simply sighed and said, “It’s too late”?

Last time around, Saul took a lot of courses he hated. This time, he focused purely on pleasure — on things like jazz appreciation and writing.

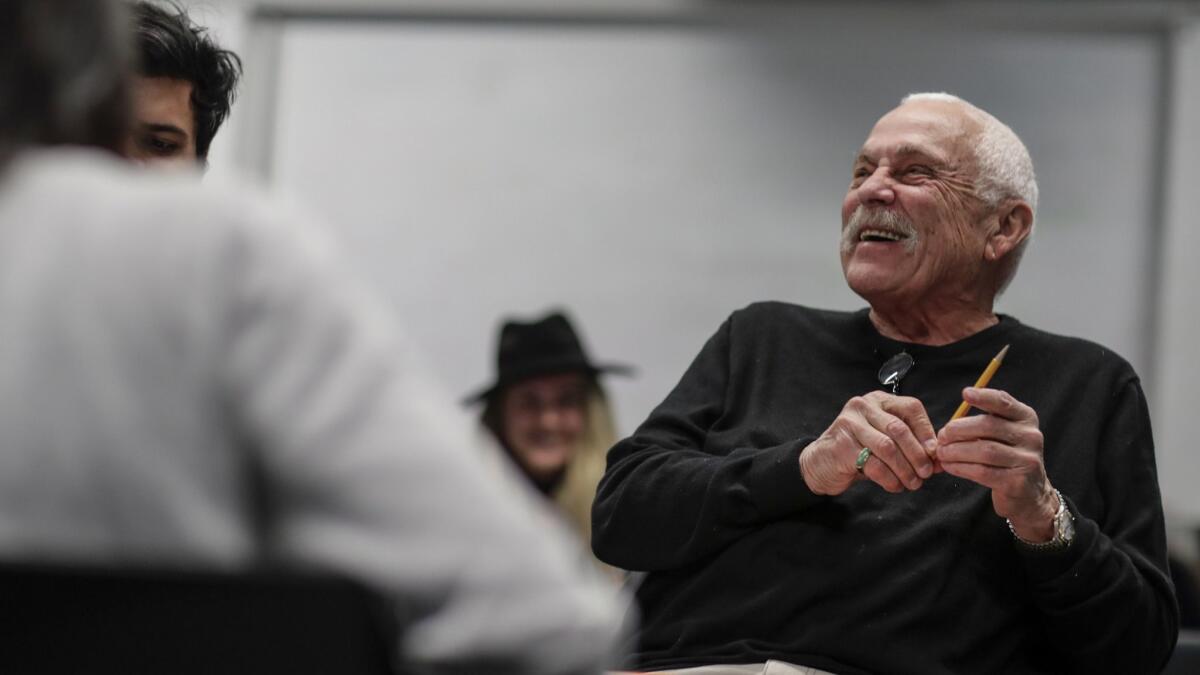

When I first met Saul at an evening scriptwriting class, I did a double take. The burly guy calling out my name in the hall looked to be in his 60s, and he was dressed like everyone else, if a touch more elegant — cream-colored jeans, K-Swiss sneakers, bright blue socks covered in a vivid white-and-yellow pattern of fried eggs. His classmates came up to him and chatted and joked. Saul is a funny, punny guy — and he made them laugh.

Really the only things that set him apart, aside from his white hair, were that he didn’t arrive with kombucha or a water bottle and that he sat right up front in class without fidgeting, jotted his thoughts down on a pad in pencil, and enthusiastically drank in his surroundings, unbeholden to a screen.

He exuded joy just to be in the room — which struck me all the more forcefully later, after I learned about the roller-coaster climbs and dips of his life.

Saul is old enough to have, as a 13-year-old boy, snagged an autograph from Babe Ruth at a coffee shop. (The writer Paul Auster once read his account of the moment on NPR’s National Story Project.)

He’s also old enough to have grown up long before people spoke of finding their bliss. It took him so many years in the woods, blind to the breadcrumbs, to reach his creative home.

In his Cleveland childhood it was a given that he would be a patent attorney like his father. Never mind that he would need advanced math and science, and he wasn’t even good at them in high school. He set off to study engineering at the University of Wisconsin — and soon found himself so miserable there that he dragged a chair onto a frozen lake and contemplated ending his life.

“I would spend all of my time reading Time magazine and writing down definitions of words to expand my vocabulary,” he told me, but still — even after flunking out of Wisconsin — he plodded along, gamely following convention.

That meant a few more unfocused undergraduate years and then a couple in law school — which in those days you could enter without an undergraduate degree, and which he enjoyed only for the chance it gave him to put out the school paper.

That also meant marrying his high school sweetheart young, quickly starting a family, and settling into a stifling predictability he describes as “show, eat, home” — once a week go out to the movies with your wife, probably on a double date, stop for a corned-beef sandwich after, go home. He bucked against it. The marriage fell apart. He wound up raising the three kids.

He had two more wives, one the love of his life and the mother of his fourth child, but her alcoholism forced him to take their daughter and leave. That’s when he left Cleveland at the age of 61 and came to L.A. — like so many others, hoping to start anew.

The third wife, who took him to Northern California, was a wrong turn, he says. And in the course of his time with her, his business ventures failed and he found himself “in a very bad place.” He’d once had fancy houses and a six-figure salary. He returned to L.A. seven years ago with very little materially. Now he lives in a rent-controlled apartment on the last of his savings and his Social Security.

But as for that bliss, he seems to have discovered it in what was left behind after so much else in his long life had been shed.

He has four children and eight grandchildren who love him. He’s made himself a cozy world in Los Angeles. He’s found an extended family in his Write Away writing group that meets weekly at a local library. He gets together with his young college friends and sometimes joins them doing readings at a bar called Gravlax. He recently had an eagle on the Encino Golf Course.

And every night sometime around 6 or 7, he goes to the freezer where he keeps his London Dry Gin and a glass and makes himself a martini with a splash of orange bitters and a twist of lemon. He puts it on a small table in his bedroom, beside the large, comfy leather chair he sinks into, and picks up a novel and begins to read and sip, while his aged cat Nate keeps up a steady chorus of comment.

One wall of his bedroom is covered with framed images of writers whose work he’s devoured — F. Scott Fitzgerald, J.M. Coetzee, Elmore Leonard, H.G. Wells, Vicki Baum. Over the years, he says, in that long gap between classes, they taught him a lot of what he most wanted to know.

Every day now, whenever he feels like it, Saul writes. He’s come to understand that he should have always been doing it.

Since he found his calling in fiction in his 60s, he says, he’s had logorrhea — the opposite of writer’s block. Case in point: he wrote a fictional account of his graduation at least a week before it happened. In it, an 85-year-old man named Darby Winters finds himself about to get his degree, “a thousand-year-old egg amidst a carton of freshly laid.”

Saul’s eldest daughter, Amy Isler Gibson, just got her fifth degree at the age of 61 — but said she skipped that ceremony to be at his because “it’s just such a validation of his passion for life.”

His son Seth, 60, told me his father has such a childlike wonder and openness, he’s like “a picture window with feet,” a description I found apt.

On Tuesday, as Saul lived the moment for real, the setting sun seemed to hit him, and he shone.

Nita Lelyveld wants to know your L.A. story. Email her at citybeat@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.