Offering Laborers a Helping Hand

- Share via

CARLSBAD, Calif. — They call her the rice and beans lady.

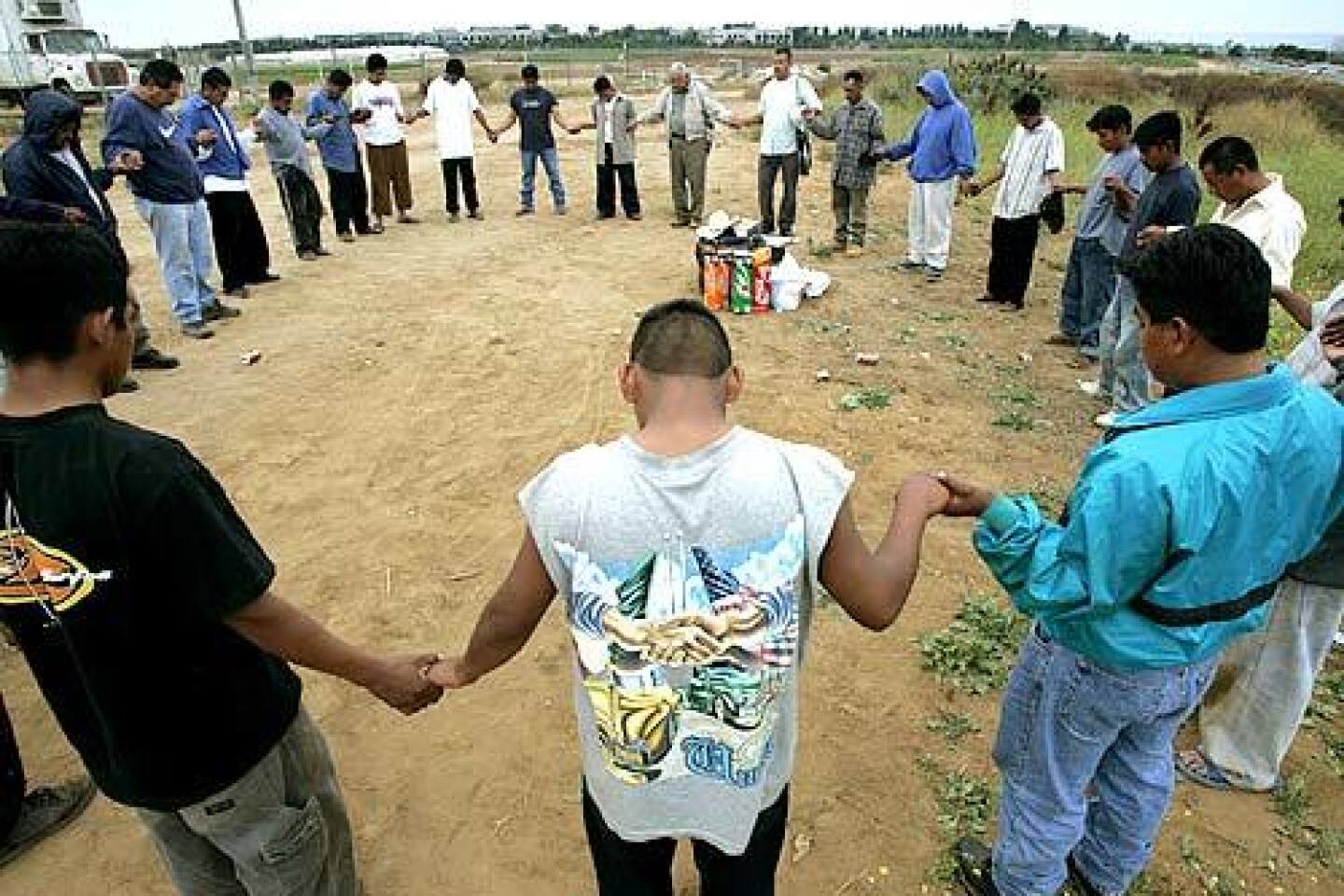

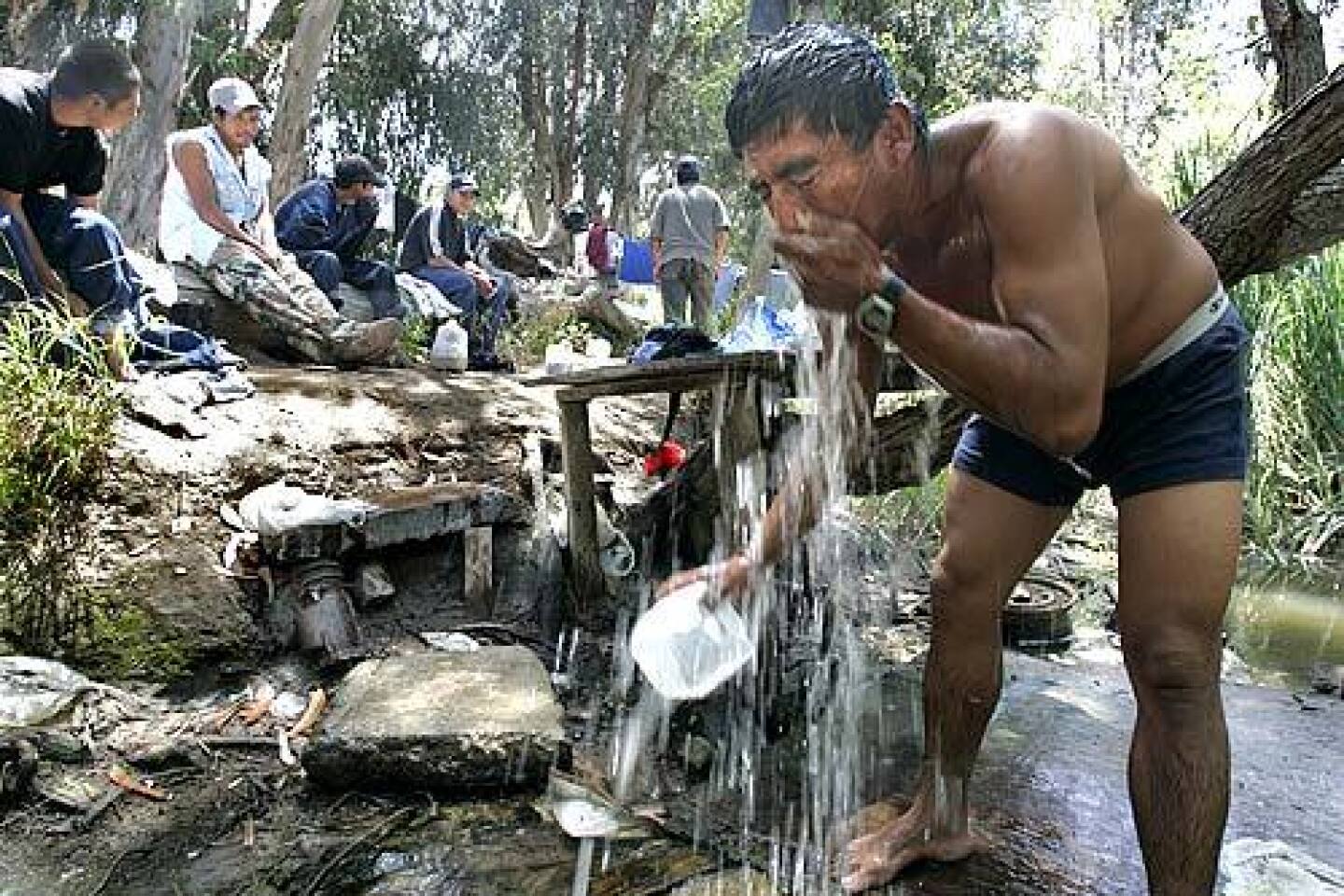

Eight years ago, Barbara Perrigo loaded up her car with homemade food and pulled up at a clearing on the side of Cannon Road, less than a mile from the turnoff for Legoland. She sent her sons into the scrubby bushes, down steep paths dotted with hidden shacks, shouting “comida,” or “food.”

Perrigo has been there every Sunday since, feeding as many as 60 farmworkers at the peak of strawberry season.

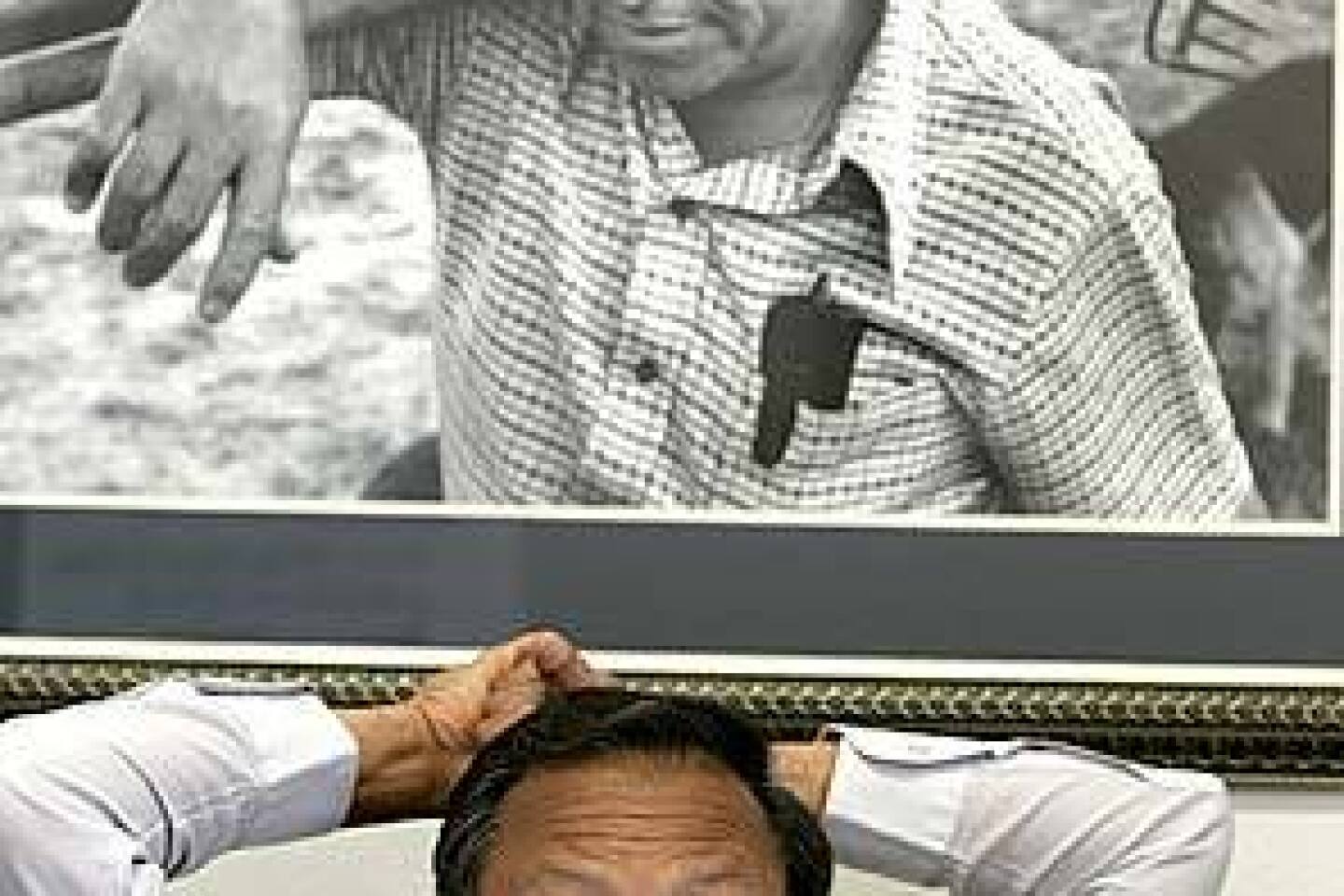

Mike Wischkaemper was a local lawyer who knew nothing about the farmworkers living in the camps except that Carlsbad residents opposed proposals to find more permanent housing. Dorothy Johnson, an attorney who runs the California Rural Legal Assistance office in Oceanside, invited him to meet with some of the people her organization was fighting to help.

The experience made him a convert; he learned Spanish and organized water handouts on Sundays and English classes Tuesday nights at the local church.

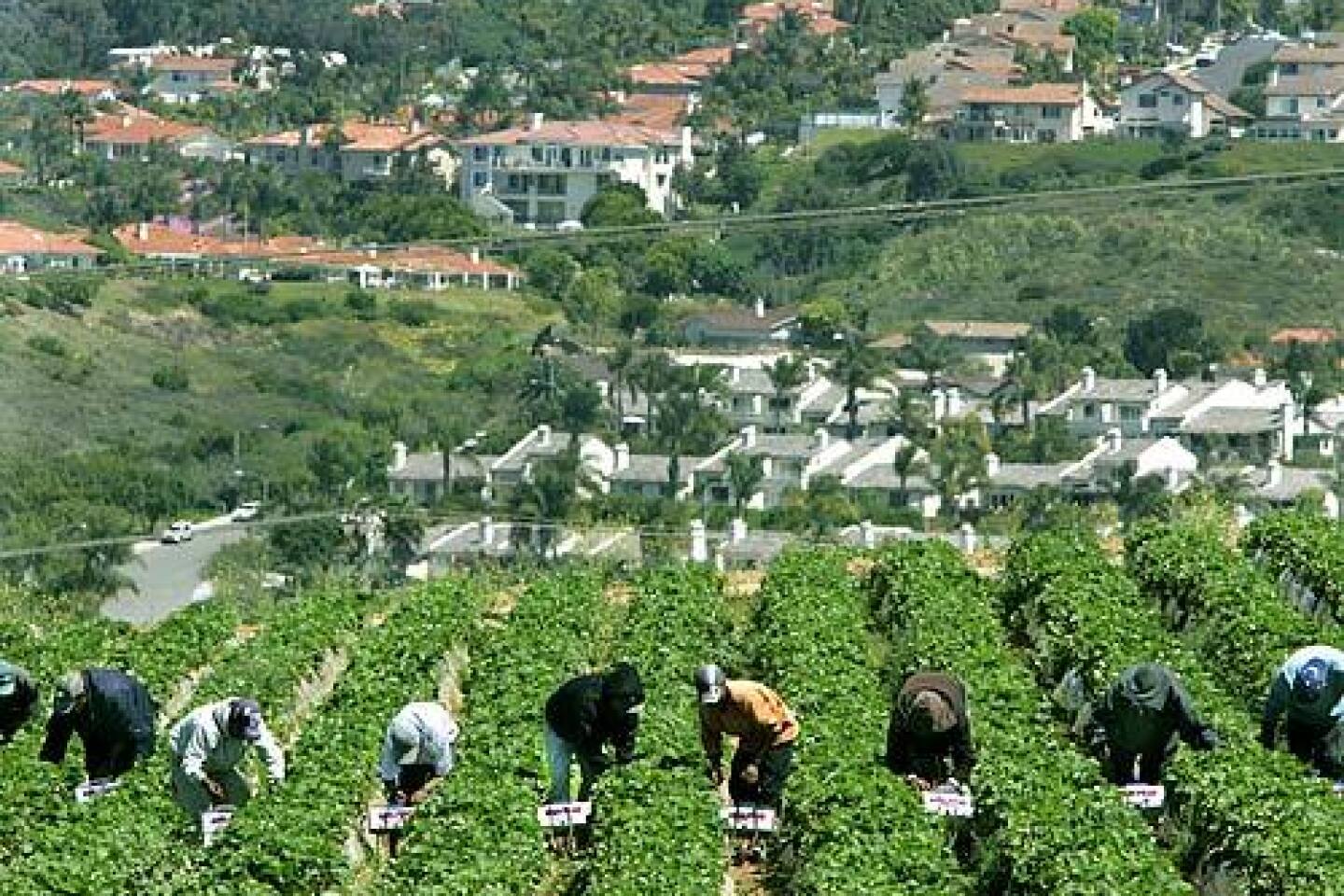

Perrigo, Johnson and Wischkaemper are mainstays of the loose support network for farmworkers in north San Diego County, where many live in plastic-and-plywood shelters nestled in the canyons. The three help meet basic needs — food, clean water, rides, medical help in a crisis — and offer advice — how to figure out if growers are paying overtime correctly, how to file income tax returns.

Others help fill the roles once played by the United Farm Workers. Volunteers offer improvised English lessons. Two former farmworkers from Oaxaca translate from Mixteco, a lifeline for workers who don’t even speak Spanish or know any written language. Lunch truck operators sell food, extend credit, translate documents and call for help.

When a worker fell in the tomato fields recently and separated his shoulder, the lunch truck owner known as El Guerrero — because he comes from the Mexican state of Guerrero — called the legal assistance office to make sure someone knew the injured man needed help.

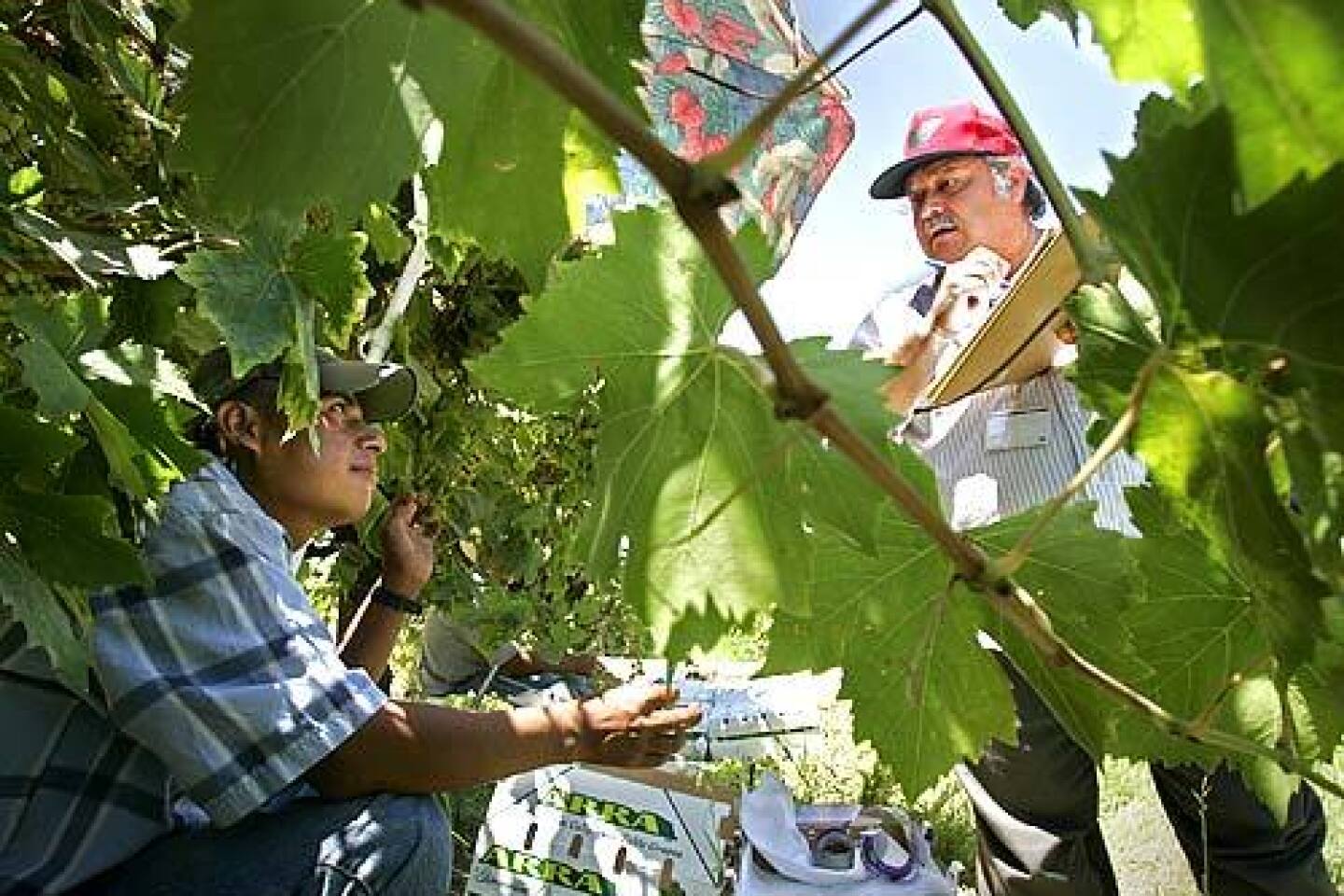

Johnson and her staff of three, part of CRLA’s statewide network of 22 offices, provide the most broad-based legal support, focusing on workplace rights, although federal funding limits the organization to helping documented workers. Johnson has also been a leader in efforts to negotiate a better housing solution for the farmworkers.

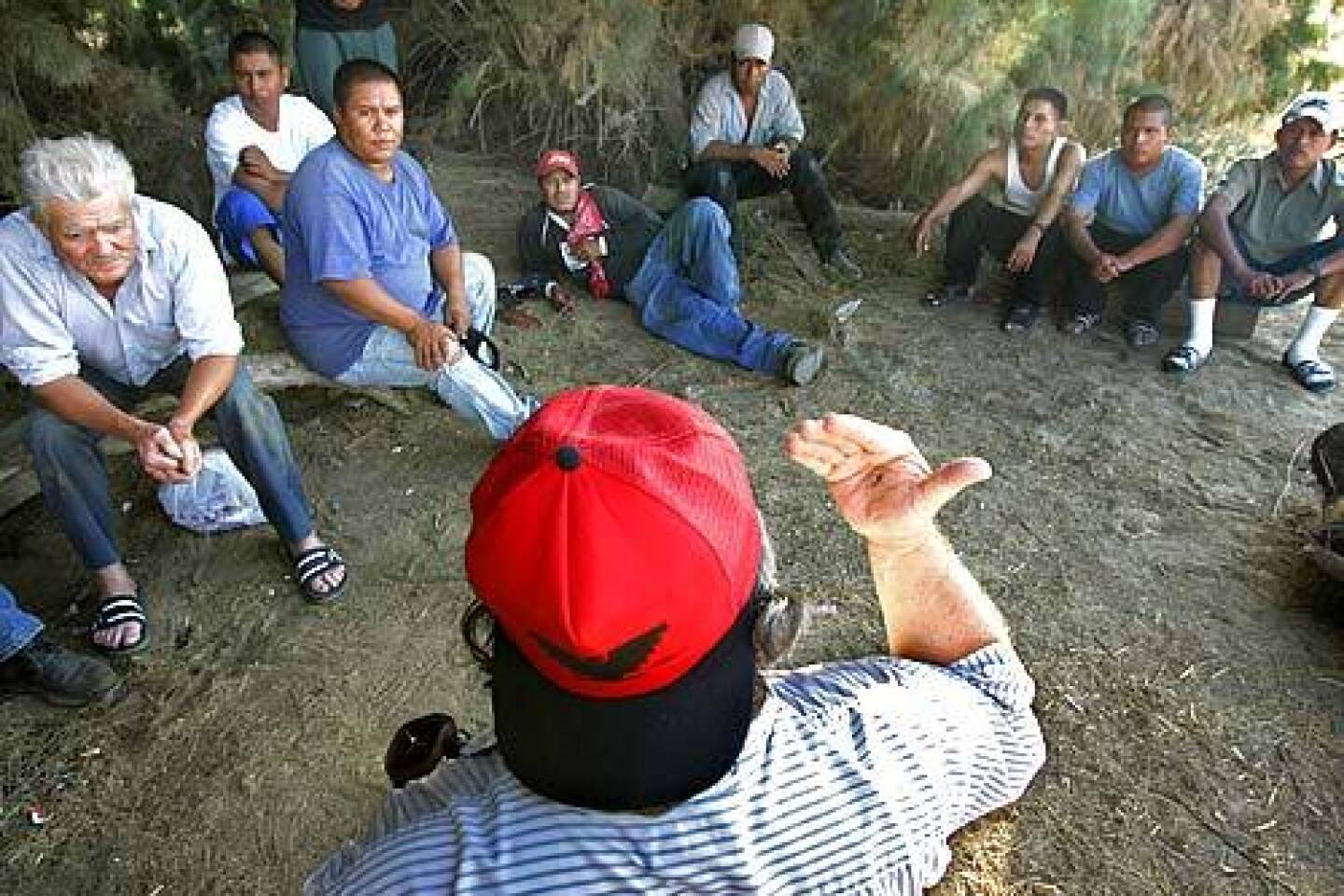

Monthly meetings sponsored by the legal assistance group offer workers a respite from the monotony of the fields, along with practical advice.

One night, farmworker Fernando Bernadino good-naturedly let co-workers paste red dots all over him indicating spots where they thought he would hurt after a day in the fields, a prelude to experts demonstrating ways to lessen the daily pain.

Usually the North County Health Clinic’s van parks outside the meetings; last year the clinic equipped the van with a dental office as well. Many farmworkers have never seen a dentist.

Rates of diabetes, high blood pressure and AIDS are far above average. If tests are positive, the health workers will call Juan Ramon or Jose Gonzalez, friends who lived together for about five years in the camps of San Diego when they first came from Oaxaca to Southern California more than two decades ago. Gonzalez, who is trilingual, works as a night manager at Rite Aid and also as a certified court interpreter in Spanish and Mixtec.

“You have to really think about leaving a fingerprint,” he said. He wants new immigrants to know their rights, things it took him years to learn. “It’s their choice. If they want to demand their rights, it’s them that’s going to do it. We will support them.”

Sometimes issues in the camps are more basic: How to throw out the garbage that piles up in the canyons, mounds of boxes, papers and beer cans. Perrigo brings trash bags, Wischkaemper explains the need to keep the camp clean and charges Bernadino with making sure each worker brings out a full bag of trash. Perrigo carts the bags away.

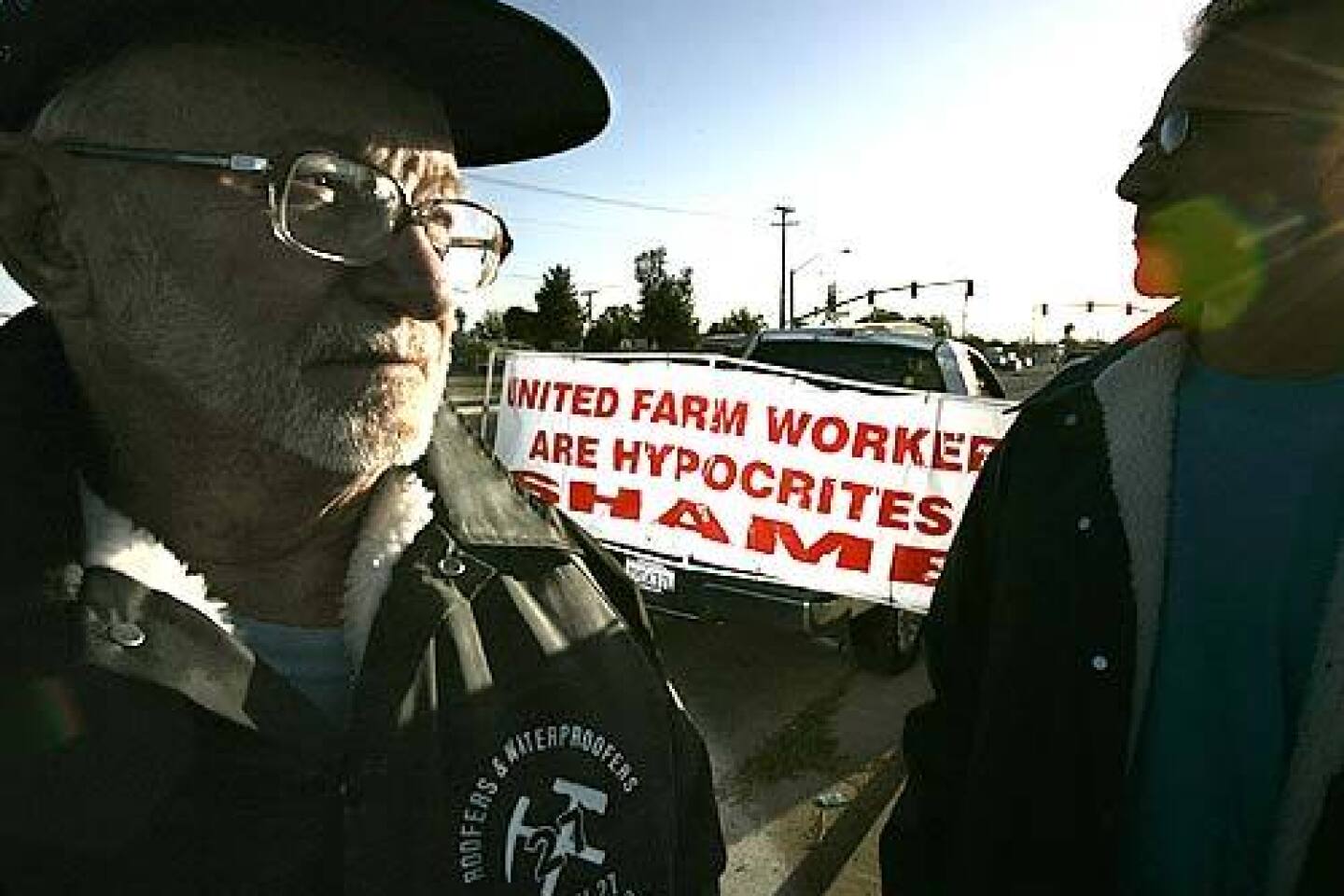

Johnson, the CRLA lawyer, began helping farmworkers more than three decades ago as a UFW volunteer when she left her Seattle home and camped out on the floor of the then-UFW headquarters in Delano. She remembers looking at the first contracts the union negotiated and being surprised that things she took for granted were considered major victories.

“And 35 years later,” she said, “we’re still fighting over bathrooms and water.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.