A dying mother’s plan: Buy a gun. Rent a hotel room. Kill her son

- Share via

I: A desperate choice

Lai Hang had four months to live and no time to waste.

On the day in 2015 when she heard her cancer prognosis, she filled out the paperwork and began the 10-day waiting period to buy a handgun.

Then she asked a childhood friend, Ping Chong, to hold onto her records, including the death certificate of her husband, who had died of cancer three years earlier.

Chong, reluctant to confront the prospect of her dear friend’s death, refused at first.

But Hang, who never shouted, pounded the table with a fist weakened by chemotherapy and yelled at Chong to take her request seriously.

Chong agreed.

She knew that Hang was deeply concerned about what would happen to her 17-year-old son, George, after she died.

No one knew just how desperate Hang had become.

II: A family unravels

Chong had begun to glimpse signs of chaos in Hang’s home months earlier.

A smashed iPad.

A shattered soap dish in the shower.

A broken door knob.

Hang explained away the damage as accidents, but Chong suspected Hang was hiding something.

The two grew up in Laos and attended grade school together. Their families moved to Hong Kong when the women were teenagers, and Chong remembers cramming into each other’s tiny apartment for dinner parties on the weekends.

Called Eva by her friends, Hang was beautiful, smart and ambitious, Chong says. She won a scholarship to study graphic design in Tokyo at a time when it was rare for women to go to college. In 1992, she moved to the U.S. to marry.

Key points about mental illness, violence and Asian Americans »

She and her new husband, Peter, opened a printing shop on Main Street in Alhambra, and for two decades they lived the American dream. As Quality Printing and Graphics prospered, the couple bought a small house in a gated community in Rosemead.

They gave birth to George, in 1998, the same year Chong’s son was born.

When the two women reunited, Chong was overjoyed that serendipity had placed them on such similar life paths; that they could be friends as children, teenagers, wives and mothers; that their sons could grow up together.

But in 2012, Peter was diagnosed with cancer. Then doctors found tumors in Hang’s chest and brain.

Peter died during George’s freshman year at Gabrielino High School, and the boy took the loss hard, Chong says. He withdrew, and his relationships with friends changed.

During her friend’s cancer treatment, Chong visited Hang’s home in Rosemead several times a week, bringing mango or coffee ice cream to ease the ache of chemotherapy.

That’s when she began to see the signs of familial distress:

The garden Chong had helped George plant after his father’s death — bell peppers, tomatoes, strawberries and eggplants — was repeatedly destroyed.

A table in the house was covered with books and papers about Adolf Hitler and a hand-drawn stencil of a swastika.

Chong’s own son, who was in the same class as George, had done the World War II project. But that was months earlier. Why was George’s Hitler stuff still around?

Chong never heard Hang say anything negative about her son.

“If there was something wrong with George,” Chong says now, “only she knew.”

But one day, after his report card came back full of F’s, she described him with an odd term: seoi zai.

It’s a Cantonese phrase that in its most innocuous use means naughty or petulant. In the term’s darkest connotation, it means “wicked child.”

III: Suffering in silence

At some point after his father’s death, George received a diagnosis: schizophrenia.

Taboos about mental illness pervade every culture, and research shows that Asian American families are the least likely among all racial groups to use mental health services.

Hang did seek treatment for George. But even when Asian American patients find professional help, their family and friends often struggle to speak openly about the subject, and so miss out on that important piece of informal therapy says Glenn Masuda, associate director of the Asian Pacific Family Center, in Rosemead.

And silence, experts say, can foster a deep, unhealthy relationship between a caring parent and a mentally ill child.

Hang once asked Chong, who works in a traditional Chinese pharmacy, for her opinion on George’s prescription. Chong glanced at it too quickly to read anything, told her to follow the doctor’s recommendation and quickly changed the subject, she says.

Another time Hang asked Chong to accompany her to one of George’s appointments at the family center in Rosemead, but Chong felt it was improper to listen. She turned her head away and kept her distance so she could not hear.

They were as close as friends could be. But it was as if they lacked the emotional vocabulary they needed to discuss tragedy directly, Chong says.

Both were raised to believe the proper way to respect another family’s pain was to give them privacy and spare them the social embarrassment of public suffering.

To speak of Hang’s burden, Chong thought, would only make it heavier. So she kept silent while Hang wrestled alone with the question of what would happen to George after her death.

IV: Mass murder on TV

Schizophrenia, experts say, is prone to misinterpretation under any circumstances, and George’s surfaced at a particularly troubled time for the family and the nation.

News about mass shooters scrolled regularly across Hang’s television screen.

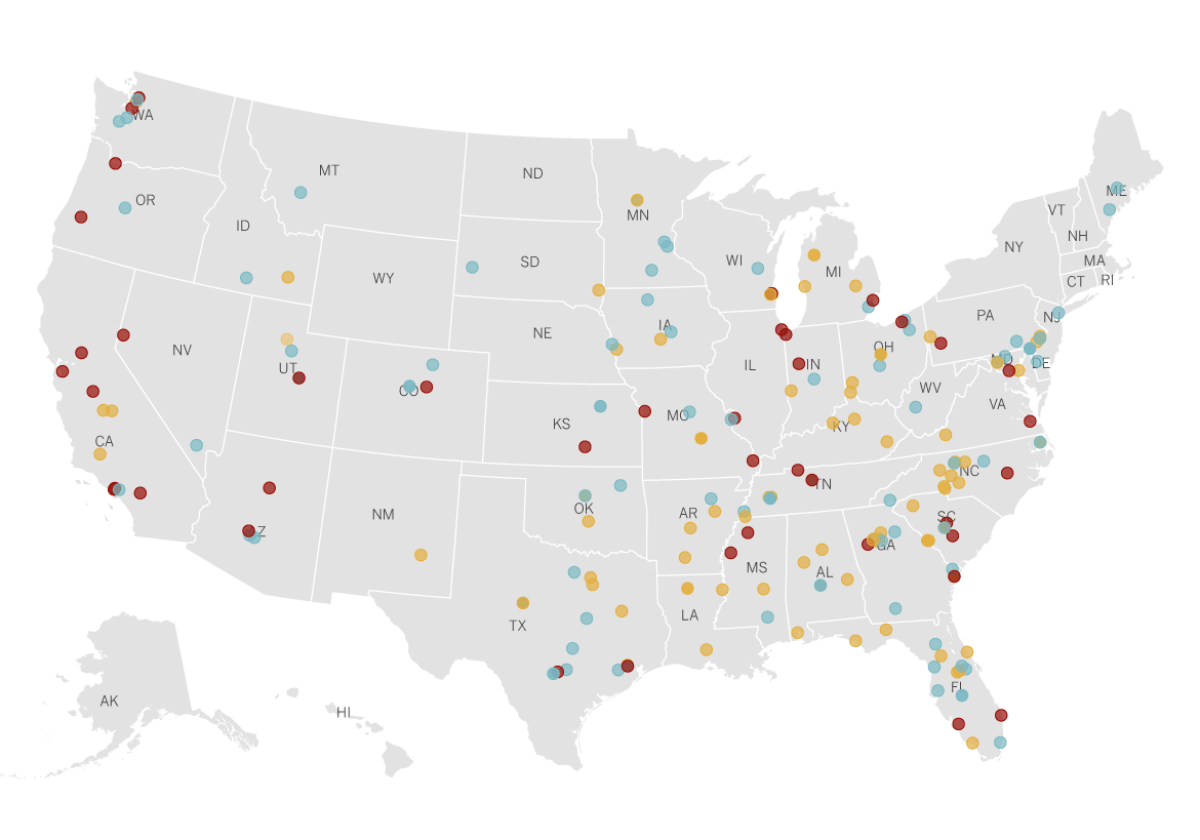

School schootings since December 14, 2012

In 2012 — George’s freshman year — James Holmes shot and killed 12 people in Aurora, Colo.

Later that year, Adam Lanza shot 27 people, including 20 first-grade children, in Newtown, Conn.

In George’s sophomore year, as he began to fail his classes and withdraw from friends, Elliot Rodger killed six people in Isla Vista.

Mental illnesses such as schizophrenia are not significant contributors to violence in America, experts say.

When people don’t understand that people with serious diagnoses can lead fulfilling lives, they hit the panic button.

— DJ Ida, director of the National Asian Pacific Islander Mental Health Assn.

Still, media reports linking mental illness and violence have grown in recent years.

The fallout from such portrayals, says DJ Ida, director of the National Asian Pacific Islander Mental Health Assn., is that families internalize societal fears about mental illness and mass shootings.

“When people don’t understand that people with serious diagnoses can lead fulfilling lives, they hit the panic button,” Ida says.

A few weeks before Hang submitted the information for a background check and began waiting for her handgun, Dylann Roof, a white supremacist with a bowl haircut and vacant gaze, shot nine people in a South Carolina African Methodist Episcopal Church.

George became fixated on him, and Hang grew more worried.

Once, in Chong’s presence, she wondered aloud about the shooters: Why hadn’t anyone done something to stop them?

V: The roads not taken

There is plenty a dying parent can do to create a safe future for a troubled child; plenty that friends or family can do when a loved one seems dangerous.

George was about to turn 18, at which point he would be beyond Hang’s legal control. But she could have asked a court to find him incapable of handling his own affairs and appoint a conservator.

She could have convinced police or mental health professionals that he was an immediate threat to himself or others and had him taken into protective custody. That might have led to long-term psychiatric care.

At the Asian Pacific Family Center, a Asian immigrant father with a fatal cancer diagnosis recently came in with his schizophrenic daughter, tortured by the same concerns that Hang had about George, says Masuda. Getting care for his daughter and understanding that she could have a future allowed him to die peacefully.

But Hang, Chong says, was taught that a son’s troubles are a mother’s sole responsibility.

“Mothers, we are the most miserable people in the world,” Chong says.

VI: ‘I sent him away’

Details of George and Hang’s final days together can be gleaned from court records, L.A. County Sheriff’s reports and interviews.

A few days before Hang’s waiting period ended, she and George went out for one of his favorite meals, pad thai.

On July 27, 2015, she picked up her new handgun and checked herself and her son into a motel on Valley Boulevard, authorities allege.

When George fell asleep, Hang shot him twice in the chest, then crawled into bed beside him, authorities said.

For several hours, she stroked his hair as his blood soaked into the mattress.

She wanted to say goodbye, she allegedly told the officers who responded to the scene.

That evening Chong received a call from George’s cellphone. It was Hang.

What’s wrong, Chong asked. Where are you? Where is George?

“I sent him away,” Hang said.

She believed she was doing the right thing. She didn’t want others to suffer.

— Det. Eddie Brown

During the investigation, Hang told Det. Eddie Brown of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department that she had killed her son because she thought he was dangerous.

She said that he had been playing violent video games.

“She believed he was at risk to become a mass shooter,” Brown said. “She believed she was doing the right thing. She didn’t want others to suffer.”

She didn’t shoot herself, she told authorities, because she wanted to punish herself for what she had done.

A few weeks after the homicide, Chong visited Hang in jail and asked her friend to explain.

Hang turned her face away.

Burn all of our pictures, she told Chong. I don’t want anyone to remember us.

In jail, the cancer spread through Hang’s body, taking the vision in her left eye, paralyzing her.

In December, a judge determined that Hang’s terminal illness qualified her for compassionate release to a nearby hospital.

Chong brought flowers, prayer beads and a tape of Buddhist chants to Hang’s bedside.

She leaned in and whispered an absolution: You are not a prisoner anymore. You are not a criminal anymore. Nothing that happened before matters.

Then she returned home to her own family.

Around 4 p.m., Hang died alone, leaving Chong to struggle with how to remember her best friend.

“People will only know her as the mother who killed her son,” Chong says. “But she was more.”

Twitter: @frankshyong

ALSO

Previously deported hit-and-run suspect criminally charged with federal immigration violation

Gunman in San Diego pool shooting 'extremely distraught and depressed,' frantic sister told police

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.