The artist behind the iconic ‘running immigrants’ image

- Share via

On the fifth floor of Building Two of Caltrans’ San Diego compound, a bear of a man with a quiet voice sits in a cubicle straight out of “Dilbert.”

He is surrounded by blueprints of overpasses and trucking lanes. There are photos of his son, training seminar certificates, cups of Jell-O and bottles of Tabasco, the remnants of 27 years at the same job, 27 years of eating lunch at his desk, 27 years of unremarkable government bureaucracy -- with one notable exception.

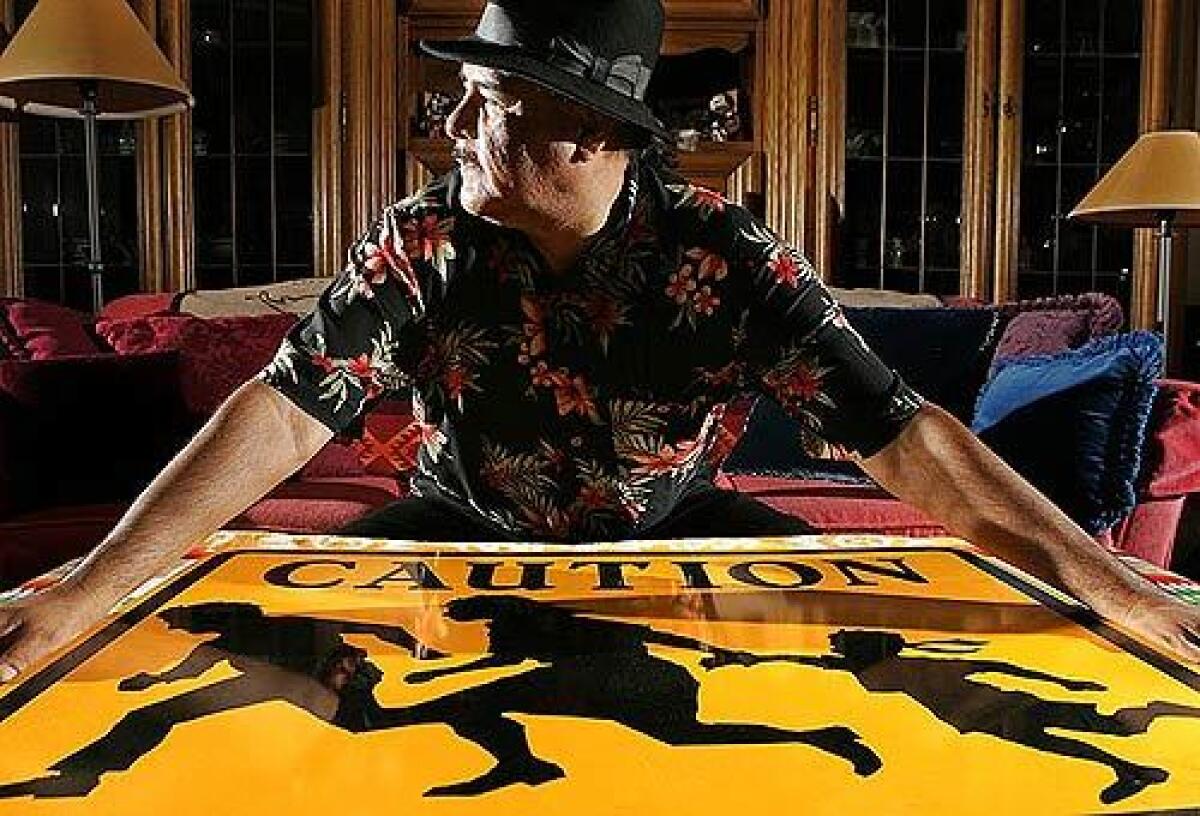

“Here it is,” says John Hood, riffling through a portfolio. The drawing he pulls out was done as a prototype; it is crude and a bit frayed. But its characters, captured in silhouette, are instantly recognizable.

There is a father, leading the way with a clear sense of urgency, bent at the waist. A mother, running behind him, despite the prim dress that hugs her knees. A little girl, holding her mother’s hand, unable to keep pace, her feet barely touching the ground, her pigtails -- everyone knows the pigtails -- flowing behind.

In 1990, the image would be projected onto black vinyl, traced with a knife blade, glued onto yellow signs, topped with one word -- CAUTION -- and placed on the shoulders of freeways, mostly along Interstate 5 north of the Mexican border.

The sign served as a warning that drivers could encounter people racing across the interstate -- most of them trying to get from Mexico into the United States. It would become one of the most iconic and enduring images associated with the nation’s war over illegal immigration. And it would leave John Hood, now 59 years old and preparing to retire, conflicted and ambivalent about his strange legacy.

“What does it mean,” he asked the other day, after sifting through his work, “to live a meaningful life?”

Hood was always an artist, always an observer.

A Navajo, he grew up on a reservation in a corner of New Mexico where people lived 7,000 feet above sea level, amid junipers and cedars, mountain lions and coyotes. His parents were illiterate; his home had no electricity or running water, and he slept on a pile of sheepskins.

“My childhood,” he said with a smile, “was fulfilled in every dimension.”

Hood went to boarding school, but much of his education came at home. His grandmother showed him how to shear their sheep and spin the wool into yarn. His grandfather showed him how to pick medicinal herbs and how to gather bright pollen from the tips of cornstalks to use in traditional ceremonies.

Hood illustrated many pieces of his life, sometimes etching his drawings on the walls of his family’s barn.

“I used to watch the animals too,” he said. “A horse will be staring away from you, but he can see you with his ears; you can see his ears going back and forth. It sounds weird, but you can learn from that. You can learn to be aware. You can learn to see.”

Before he finished high school, he enlisted in the Marines. It was 1968. Within a year, he was in Da Nang. His tour in Vietnam was terrifying and defining. He often volunteered to walk “point” on patrol, and carried C-4 plastic explosives to blow up booby traps. His platoon called him “Chief.”

Being an infantryman came naturally to him, or as naturally as it can come. Some of the tricks he used to survive had roots back home -- the way, for instance, that he could often locate the enemy by studying the sunlight filtering through the jungle canopy. He was in, he estimates, at least 20 firefights. Many of his comrades didn’t make it.

“I lost a lot of things there,” he said. “Friends. Youth.”

At the end of his tour, he was sent back to the United States and stationed at Camp Pendleton. He was sure the war had left him with no enduring wounds, but he was wrong. He began having nightmares that a man was chasing him, a man he was helpless against. He went AWOL and got caught. He started drinking. His marriage fell apart.

Through the G.I. Bill, he started taking classes in fine arts at San Diego State. He was a particularly fine graphic artist, with an eye for delicate detail, for the interface of light and shadow. Shortly before he married a second time, he was hired as a graphic artist at the state Department of Transportation.

His portfolio would soon start filling up with routine projects: the cover of the department’s phone directory, photo manipulations showing what freeways would look like with new carpool lanes. Then, in the 1980s, pedestrians started getting killed on California interstates with alarming regularity.

The state declared two “danger zones” along I-5.

The first was in the San Ysidro area, just north of the border. There, in just a few years, 100 people had been struck by cars and killed as they attempted to race into the United States.

The second was an eight-mile stretch between Oceanside and San Clemente, near the immigration checkpoint. There, coyotes -- human traffickers -- would order migrants to spill out of cars and trucks and run into the surrounding hills, a route that often took them across lanes of traffic. Another 30 people had been killed.

The dead were typically the last ones across the road: the very young and the very old.

The state hurriedly assembled a task force, which included several agencies.

Drivers, the state decided, needed to be alerted to the possibility of migrants running across traffic lanes. There were just a few graphic artists in the San Diego office; the task fell to Hood. “It was just part of the job,” he says, though he knows it’s more complicated than that.

There were several versions, some stuffed in the envelopes of residential electric bills, other posted at rest stops. In some, the characters had eyes and other features; officials felt those would be too detailed for motorists to discern at high speed. In another, the mother juggled a baby and a sweater, but that too was deemed overly complicated for the freeway.

“People are going fast,” Hood said. “It had to be simple.”

In the end, he thought about family.

“When you think about a little girl, you are more sensitive to something horrific,” he said. Plus, he said, he could give the girl pigtails -- a visual tool that made it easy to demonstrate the idea of motion, of running.

The signs, which went up in 1990, have been stolen, vandalized and -- increasingly obsolete as immigration routes have shifted to Arizona and Texas -- taken down. There are just a handful left today; few people attempt to cross I-5.

But the image has never been more prevalent -- or relevant.

It has been seized upon by people on all sides of the immigration debate. Anti-immigration groups offer T-shirts that depict the same family -- being chased by a man with a gun. On Olvera Street in Los Angeles, the image is used as a symbol of immigrant pride.

Then there are those who have adopted the image simply because of its notoriety, including shops that offer T-shirts showing the same family carrying surfboards. In a signature installment of his TV show “Mind of Mencia,” comic Carlos Mencia -- whose family immigrated to East L.A. from Honduras when he was an infant -- filmed a segment based on the sign. “Maybe,” Mencia says at one point in the segment, “it’s telling them: ‘Run across the freeway. Just do it really fast.’ ”

A photograph of the sign is hanging at the National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

“In museums, we are constantly looking for objects that transcend their own history,” said Peter Liebhold, chairman of the museum’s Division of Work and Industry. “This is, without a doubt, an icon of the current immigration debate. It’s taken on meaning that was never intended.”

Hood does not fit tidily on either side of the immigration debate. He is a registered Democrat, though he has voted for Republicans. He is torn about the upcoming presidential election. He does not abide bigotry -- or political correctness.

Hood knows something about foreigners coming onto your land; his people were rounded up and marched from their homes after the Civil War. He also knows something about poverty, about taking risks and leaving behind what you know in pursuit of a better life.

“I heard a commentator on talk radio the other day,” Hood said. “He said: ‘I want my country back!’ American Indians have been saying the same thing for a long time. Really, whose country is this? Why is there so much hatred in this world?”

He talks about the immigration war only grudgingly; he has no desire, he says, to get in the middle of it.

Soon he will retire. He hopes to return to the place he still calls home, to the reservation in New Mexico.

“There is nothing else that I need in life, so I think I’ll go back,” he said. “Water the plants. Water the heart.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.