RAP GETS RELIGION:

- Share via

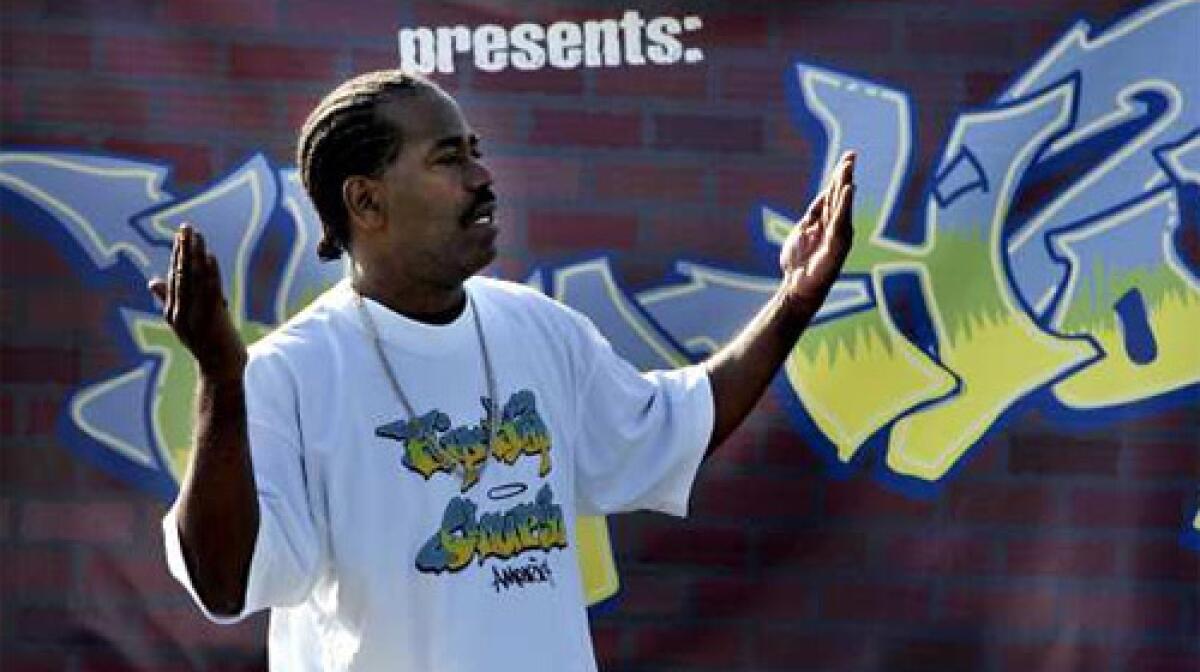

“The gangs have the right idea!” A-Man shouts from the flatbed of a semi-truck trailer serving as the stage for Hip Hop Church America outside the Crystal Cathedral on a hot fall afternoon. “But instead of killing each other they should be out there killing witches! When they’re out there slaying other gangs they should be slaying demons!”

A-Man, 13, born Alex Robnett, is in the eighth grade at a middle school in Carson, but he is also a gospel rapper and disciple of the growing hip-hop church movement. His cornrows and the black suit slacks and vest he’s wearing may seem an incongruous stylistic mix of street and pulpit, but they reflect the occasionally clashing relationship between rap and religion.

The origins of the hip-hop church movement are perhaps as disputed as the origins of rap itself, but what can’t be denied is that in the last several years, rappers, DJs and emcees have started changing the face of that old-time religion. Christians have staked out ever-expanding turf within the hip-hop nation, beginning in 1985 with Stephen Wiley’s “Bible Break,” generally considered to be the first commercial gospel rap record, and leading to the robust “urban inspirational” genre fueling record labels, websites, churches and careers today.

Los Angeles is one of the latest stops on hip-hop’s religious conversion tour, which has grown beyond a novelty act or religious sideshow into a cultural and religious phenomenon recognized by the World Council of Churches and influencing countless congregations across the country.

L.A.’s own Gospel Gangstaz are recognized by leaders of the current hip-hop church movement as pioneers who set the standard for God rap in the early 1990s, picking up a Grammy nomination in 2000, and local groups Tunnel Rats and IDOL King represent the legacy.

Although Hip Hop Church America’s October event was sparsely attended, it was notable that the famous bastion of Christianity in Orange County would welcome gospel artists such as rap legend Kurtis Blow, LL Cool J producer Battlecat and God rap newcomers 2Five and A-Man. Bobby Schuller, host of the event, is no fan of rap -- but as head of Energizing Ministries for the Crystal Cathedral, he embraced the visit of Hip Hop Church America, a special event of Blow’s musical youth ministries.

“Right now we’re just getting our roots in the ground,” explains Schuller, 25, grandson of the mega-church’s founder and son of its current pastor. “The elder Schullers love that we’re doing this. I don’t know if they get it, but they know it’s important.”

Over the last year, regular hip-hop church services have been held at the FaithDome, attracting 7,000 to the mega-church in South-Central Los Angeles, and since February, Blow, who became an early hip-hop star with his classic 1980 record “The Breaks,” has led a hip-hop congregation at Holy Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church in Inglewood that meets on the first Friday of each month.

Similar congregations -- extending the reach of such early ministries as the Hip Hop Church, Holy Hip Hop and HipHopEMass that began in Harlem, Atlanta and the South Bronx, respectively -- are fueling the vital new gospel rap genre and, significantly, a religious revival within the hip-hop nation. It’s vibrant enough, even as it grapples with the same theological rifts as its mainstream brethren, to exert a powerful pull. The result: A growing number who didn’t relate to traditional Christianity are sampling God -- and joining the debate over what Christianity should be.

Sporting baggy black jeans and jersey, Darren Hughes, 14, trekked two hours from Chatsworth to Garden Grove after hearing about the Hip Hop Church America event from a friend. “I love hip-hop,” he shouts over A-Man’s preaching. “And I love the word of God.”

Word on the street

GOD rap got major media love and street credibility after Kanye West clipped on some wings and performed “Jesus Walks” at the 2005 Grammy Awards.

Over the objections of the naysayers, the sampling had begun, and in the words of one hip-hop ministry leader, “rap and religion finally realized they need each other.” What was once considered a musical anomaly by mainstream rappers and blasphemy by some religious traditionalists has been redeemed, or at least repackaged.

One result is that for the first time the rap-religion “novelty” will get a nod from the Grammys, which in 2007 will recognize the “best gospel rock or best gospel rap.” The Crystal Cathedral event was produced largely to help promote a proposed Hip Hop Church America television series featuring Blow. The movement has undeniably helped revive the careers of other rap pioneers and stars of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Rev. Run of Run-DMC, now star of “Run’s House” on MTV; MC Hammer; and Christopher Martin, formerly of rap duo Kid ‘n Play, have all become leaders of hip-hop ministries or Christian entertainment companies.

With established hip-hop congregations in Harlem, Philadelphia and Inglewood, and two more begun last month in Dallas and New Jersey, Blow balances hands-on ministry with projects like the television series and an upcoming European tour to promote his forthcoming album, “Kurtis Blow and the Trinity.”

Other rappers have become impresarios of the urban inspirational genre. Martin, formerly known as Play, gave up performing to become executive director of Amen Films, a film and video ministry focused exclusively on inspirational and religious projects, including the documentary “Holy Hip Hop.”

But some artists have also been known to divvy up their rhymes between God and their old secular fan base. After turning his back on rap for five years while he went to college, became a minister and picked up an honorary degree from a New York Bible institute, Diddy protege Mase returned with “Welcome Back” in 2004. Although the gospel of gats and gangs was absent, the swagger remained front and center. Then in 2005 he joined 50 Cent on the soundtrack to “Get Rich or Die Tryin’ ”:

I don’t know who stabbed you, I don’t know who shot you

I don’t know who cut you, I don’t know who robbed you

But you think I know cause you know how my squad do

The potential for sending mixed messages raises concerns in some quarters. Niles Grey of the religious rap trio Remnant cautions: “People can mock or manipulate even the Gospel for music and money’s sake.”

Rap theology

MANY hip-hop disciples and the congregations and denominations embracing them are just beginning to grapple with what this new form of worship means. Across the scene, rappers are the messengers, and rhymes are their sermons, homilies and lessons. Addressing the unsettled -- and unsettling -- theological questions raised by the young hip-hop church movement, two “schools” have emerged that understand their religion, their God and their hip-hop differently.

The dominant school, known as holy hip-hop, has roots in the traditional black church and its literal interpretation of the Bible. One of its largest congregations originated at New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, a 25,000-member mega-church just outside Atlanta, that’s active in the political battle against same-sex marriage, preaches a prosperity gospel and is home to a ministry that claims “healing and deliverance” from homosexuality through repentance and acceptance of Christianity.

The other, smaller school takes a decidedly more liberal approach that finds a theological home in the HipHopEMass, an Episcopalian ministry with an ecumenical outreach. Its artists and adherents find in hip-hop’s outlaw reputation a challenge to Christian orthodoxy and a prophetic call to embrace modern society’s version of the biblical outcasts whose company, they’ll tell you, Jesus preferred. Thugs and gangsters as well as gays and lesbians are specifically included. And if none of the artists in this camp are currently found on the Christian rap charts, they’re confident that, eventually, inclusion will not only sell but save, even in the primarily conservative and evangelical hip-hop church movement.

Although artists affiliated with both schools of worship often perform and preach together, making this a rap rivalry without a body count, the rift goes to the heart of traditional Christian and hip-hop cultures, raising the question: Whose God is in the remix?

“Absolutely, the rap contains theology,” affirms Eddie Velez, an early practitioner of holy hip-hop known as Da Preachin’ Puerto Rican and the former senior director of youth development at New Birth. “The reality is Jesus Christ came into the world not to save the righteous but to save the sinners. I’m not the one to categorize sin, but the Bible -- the absolute truth -- classifies what sin is. I smoked crack, stole; others struggle with adultery, homosexuality. Sin is sin.”

The Rev. Timothy Holder, known on the street as Poppa T, co-founded the HipHopEMass in the South Bronx with Blow in the summer of 2004. As the first gay priest ordained in the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama, Holder preaches a “prophetic” hip-hop that sees scripture as dynamic, taking into account how Christian teaching has evolved historically, and therefore envisioning how it can be understood by a new generation. “The HipHopEMass.org Prayer Book” and a new CD, “The Word Was Made Flesh and Dwelt in the Hood!” -- both featuring several HipHopEMass artists -- were released this year by the ministry.

In a documentary about the seminal rapper’s life and legacy, “Tupac: Resurrection,” Shakur asks, “Who will speak for the thugs?” For hip-hop ministers such as Holder, the question is both an appeal and an indictment, challenging religion to rediscover relevant definitions of Christian love, faith and identity.

“Hip-hop holds the church accountable, and the church holds hip-hop accountable,” insists Holder, a former Democratic Party operative in the deep South. “Hip-hop reminds us that we’re all outcasts, we’re all God’s homies, black or white, male or female, gay or straight. And the church reminds us that if it ain’t love, it ain’t hip-hop.”

The differences play out vividly at the mike. In a rap called “Hope,” L.A-based holy hip-hop stars IDOL King speak directly to clergy like Holder:

Now people are actually

convinced these so-called gay pastors

are really making sense and have good arguments

Well I hate to drop a bomb, a gay pastor’s an oxymoron.

In Inglewood, associate pastor Carol Scott preaches the prophetic Christian message of hip-hop at Holy Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church. “Hip-hop challenges us to be open to the interpretation of scripture,” says Scott, who presides over the monthly service with Blow. “For me, this ministry has no walls or boundaries. When I say all are welcome, all are welcome. Let God make the distinctions.”

What is most controversial about the message of inclusion as interpreted by those preaching a prophetic hip-hop is the challenge to what they see as homophobia that’s sanctified by both hip-hop and religion. During preparations for the HipHopEMass Resurrection Tour last spring, a teenage rapper from North Carolina named Crucial turned down Holder’s invitation to appear, objecting to the priest’s sexuality. More recently, a church extended an enthusiastic invitation to the HipHopEMass before rescinding it a few days later after learning that the E stands for “everyone everywhere” -- including gays and lesbians.

To which Holder responds: “We do not compromise the central and most important message of Jesus Christ, and that is the message of love. I shout out to my colleagues and our rappers and friends in God: Do not try and compromise that message of love. That’s my sermon.”

“Whatever we do we should all do it in the name of Jesus,” says Blow, who acted as preacher and emcee on the Resurrection Tour but has mostly moved on from the ministry he helped co-found. “True Christianity is about love. Matthew 7:1 says do not judge. That’s God’s job. What I will say is that I love everybody. I believe Christ loves everybody. But I can’t tell other Christians how to behave.”

Other leaders of the hip-hop church movement have no such reticence. Indeed, New Birth’s Velez, now head of the mega-church’s Latino outreach, directly addresses the distinction between HipHopEMass and holy hip-hop: “People can say, ‘Eddie, you’re a sinner and God is using you,’ and he is. The last thing I would ever do, though, is to embrace and validate my sin.”

On message

WHETHER the hip-hop church movement is ultimately seen as simply an evangelical innovation with a canny sense of the zeitgeist or as a vision of radical Christian love -- or both -- soon it may no longer be possible to downplay or avoid such theological discussions.

If, as Velez says, “hip-hop is the bait, but Christ is the hook,” then the leaders of the movement may have to become better prepared to explain and understand their hook. However, with few exceptions -- such as Holder, the Episcopal priest educated at Harvard Divinity School, and Blow, who is transferring in January to Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena -- they are without formal education in theology, biblical studies or hermeneutics.

“Some might not have an appetite for theology,” counters Velez. “This generation seems to be hungering for information, only they’re not looking for their intellect to be challenged but their heart to be touched. As a teacher of the Bible, I think at the end of the day, theology that isn’t balanced with compassion and loving our neighbors as ourselves is void.”

But do appeals to Christian love resolve or merely raise the question: Who, specifically, is our neighbor and what exactly does Christian love look like today?

As the hip-hop church movement grows, it is clear there is more than one answer to those questions. The devil, as always, is in the details.

Several days after opening the Hip Hop Church America event, A-Man talks on the phone about being part of the first hip-hop generation whose love of rap has more to do with God than the thug life. In the background his mother, who also acts as his manager, can be heard helping frame his answers, but when asked which hip-hop prophets he follows, which message he’s hearing, his reply is unprompted and simple. “The only person I look up to is God because he’s the only one who can help,” he declares. “Anybody in rap ministries don’t look up to nobody but Jesus.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.