After he spent time on the street and in prison, this East L.A. gym saved him. Now, he’s fighting to save it

- Share via

A little before 6 p.m. in late June, nine boxers gather ringside. Long spools of hand wrap fall to the floor. Wrists, thumbs and fingers disappear inside the white tape.

Paul Hernandez, barrel-chested and no-nonsense, strides past and tunes the radio to an oldies station and the peeling licks of “Crazy Train.”

“Alright, a little Ozzy.”

Evening practice at the East Los Angeles Community Youth Center is now in session, a Monday-through-Friday routine that Hernandez has run for the last two years, bringing together fledgling fighters from the neighborhood, ages 8 to 16.

They form a circle on the floor, and a new boxer introduces himself as Angel. Hernandez feigns confusion: That makes three Angels, he says. How will he tell them apart?

They laugh as he begins the warm-ups. If he’s concerned about his future, he’s not showing it. The property was recently sold to Green Dot charter schools.

This Thursday, the doors will close, its rooms emptied out and equipment relocated to a new facility two miles away. The current location, said the president of the board, Frank Villalobos, had become too expensive to maintain.

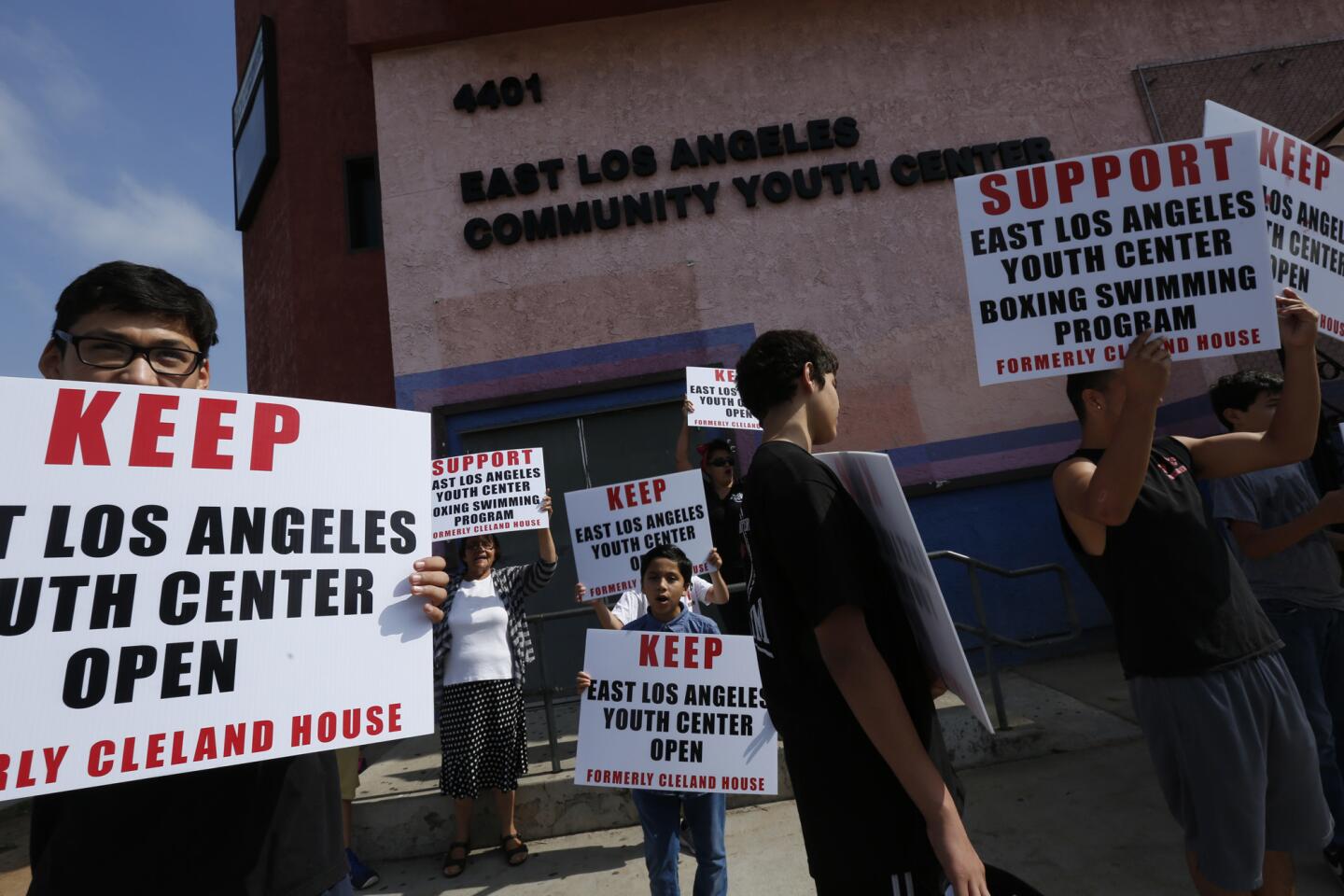

A small group of neighbors and regulars, however, are protesting the move. They call themselves East L.A. United, and over the summer, they’ve rallied. On Saturday, they hosted a barbecue-potluck and community meeting, which drew more than 100 supporters, including local boxing legends René Arredondo, Arturo Frias and Oscar Muñiz.

Hernandez wasn’t about to call it a farewell, but he’s made it clear that he and his program aren’t going to the new center. He’s not willing to give up on this property and says that he will continue to work to oppose the sale.

Hernandez grew up on the other side of Cesar Chavez Boulevard on Humphreys Avenue, just a block away near the Santa Marta Hospital, now the Hilda L. Solis Learning Academy. He fought in this gym when he was a boy; as a man, it was the place that saved him when he finally got sober.

Time on the street and in prison had once left him homeless, and it was the youth center that saved him when he returned in 2014.

In addition to his coaching duties, he has helped maintain the property, mopping the locker rooms and showers, vacuuming the community room, mowing a patch of lawn, cleaning the pool and keeping a watchful eye on the indoor basketball court across the street.

He lives in a motor home, parked at the curb, tricked out with twin headers, chrome rims and a breathalyzer wired to the ignition. And he has researched the background of the property, which was developed in the 1920s by Presbyterian missionaries “to evangelize through social services,” according to a local history. Hernandez embraced that ethic.

“I’ve been called here to do exactly what I have been doing,” he says. “My job is to train kids, and as a born-again Christian, to stand on the word of God.”

::

Los Angeles was once one of the world’s great boxing cities. Training gyms scattered throughout the Southland provided an escape from neglected circumstances, and East Los Angeles was remarkable for producing the city’s only gold medal pugilists, Oscar de la Hoya and Paul Gonzales.

Today the number of boxing venues has dwindled. The Olympic Auditorium is a church. The city’s most famous gym — the Main Street Gym where Cassius Clay once worked out — is gone, and De la Hoya’s gym is now a charter school.

In its heyday, the ring at the East Los Angeles Community Youth Center, once known as the Cleland House, might not have attracted major talent. Certified records are hard to find, its neighborhood bouts consigned to pages in old scrapbooks. But its fighters — former lightweight champion Mando Ramos and famed cut man Joe Chavez — received their share of press.

The ring had a special place in the neighborhood. Originally located outdoors, it was replaced in 1972 by local car dealers, who hoped managed fights would curb the gang violence that was claiming the area, and the Cleland House became known as the “United Nations” for its efforts at peacekeeping.

The youth center has always depended on the generosity of others. It was supported in the 1940s by Beverly Hills socialites, and when it was partially destroyed by fire in the 1960s, it was rebuilt with grants from the Fleischmann Foundation and others in the 1980s.

When the United Way cut its funding in the 1990s, the Los Angeles County Sheriff Department’s Youth Activities League took over, installing a new ring and refurbishing the gym. Five years later, when the league walked away, private benefactors stepped in.

When the famous Resurrection Gym, where De la Hoya trained, was torn down almost 10 years ago for another Green Dot school, some of its heavy-bag equipment was moved to the youth center.

But each new owner struggled with the same problems: high property taxes and an aging facility. Enrollment dropped, and two years ago, the center’s board of directors knew they had to act.

A consultant was brought in, and the board decided to sell.

“We didn’t want to, but everything was falling apart around us,” said Villalobos.

Villalobos dates his association with the center to 1978 when, as a young architect and urban planner, he helped landscape the property and secure new permits for its programs. He went on to build a career in East L.A., designing the new Mariachi Plaza and four Gold Line stations.

Last spring, the center’s board signed a lease with the owner of a former plumbing store-turned clothing outlet on Beverly Boulevard.

The new center, which Villalobos hopes to open in November, will focus on academics and technology and offer art and folklorico programs, and if the county grants the appropriate permits, there will be boxing and Muay Thai.

::

By 7 p.m., early summer sunlight and a warm breeze flood through the gym. A wall-size mural, featuring fighters, Aztec warriors and the city skyline, proclaims, “On the quest to be the best.”

The boxers have stretched and run through their shadowboxing routine and are squared off with the heavy bags, delivering left-right combinations and stepping in and away from the swaying bags.

Blanca Meza, the mother of two boxers, lays a white sheet on a nearby table. With a pencil, she sketches letters on a banner for a rally the next day.

Save our center

The Mezas live a few blocks away, and the boxing program is the highlight of the boys’ summer. Workouts have helped Nicolas, 10, with his diabetes, and Alexander, 6, who wasn’t about to be left watching.

“We don’t want to lose this place,” Blanca says.

Hernandez steps into the ring and pairs Martin Acosta with Angel Ortega. He likes Ortega, his speed and technique, and sees something of himself in the teenager, who credits the discipline of boxing for keeping him out of gangs.

“Now I can just walk away,” says Ortega.

The 16-year-olds bump gloves and step apart. Ortega goes on a quick offensive with a series of jabs to his partner’s ribs. Then he connects with Acosta’s chin.

“Come on, Martin,” Hernandez says. “You’re waiting too long. Overhand right. Again. Dig in. Dig in.”

Boxing is an easy metaphor for life, but Hernandez doesn’t overplay its lessons. They eluded him when he was their age and his father introduced him to the sport.

Their gym was a friend’s garage, their ring a square of carpet. They had room for one speed bag. Hernandez taught himself the value of light feet by studying boxers on television. His first match was in Obregon Park; he was 13.

Like many fighters, Hernandez talks a good game. Neighborhood bouts, he says, led to an event at the Olympic and one in Las Vegas. If those matches took place, their records are now lost.

At 16, his first taste of heroin left him so sick that he told himself never again. But he didn’t listen.

“The python spirit is a subtle foe,” he says, often mixing the lessons of AA with his Christian zeal. “It is a snake that engulfs you, and you don’t know it. I became my own worst enemy.”

His junkie life was marked by a brief stretch in state prison and 15 years when he got clean, found a job, an apartment and community with the Trinity Assembly of God in Pasadena.

But the python reared its head, and he ended up on the street, sleeping under a freeway bridge. Four years ago, he landed in county jail and then solitary after fighting with an inmate. It was his private descent into hell, days racked by withdrawal and paranoia.

“I was hurt,” he says. “It was all self-pity, easier to put a needle in my arms, than search for any answers.”

He came to the youth center at the suggestion of his AA sponsor, who told him that he needed to make amends to the community.

“I had no idea what this man was talking about,” said Hernandez. “I had to learn what humility was.”

The transformation, which he owes to the youth center, was as powerful as his baptism.

Looking back, he sees how with one wrong turn he could have been dead from an overdose or a gunshot wound. Instead, he is now “coach.”

::

At 8, practice is over on this hot June evening, and Hernandez unlocks the gates to the swimming pool, its emerald water a lure.

The setting sun silhouettes palm trees and the skyscrapers downtown. Traffic zips by on the 710. A sky-high Shell sign glows red and yellow, and an M-80 explodes not far away.

The boys splash one another in the shallow end. Parents and the members of Narcotics Anonymous, who had been meeting in the community center, watch enviously.

Twenty minutes later, footprint puddles are drying on the concrete. The parking lot is almost empty. Hernandez shuts the doors of the gym and clicks off the radio.

Twitter: @tcurwen

ALSO

2 men are arrested during Ryan Lochte’s debut on ‘Dancing With the Stars’

Remains found during dig for missing Cal Poly student Kristin Smart could be human or animal

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.