L.A. County’s unclaimed dead: How we reported the story

- Share via

Each December, Los Angeles County holds a ceremony to remember the county’s unclaimed dead.

After last year’s ceremony, I wanted to know more about the people who had gone unclaimed. Who were they? How old were they? Did anyone remember them?

I arranged a meeting to look at the list of the names of the people who had just been buried.

But on my way there, I got a phone call telling me that the meeting had been canceled and that the records were protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. I couldn’t have access to them.

What? These were unclaimed people being buried on public land. Their names were in public records.

I decided to continue on to the county cemetery in Boyle Heights.

When I got to the office of the crematory, the clerk at the door told me politely that I had to leave. Then the door was locked behind me.

The L.A. County Cemetery has a public office with stated business hours between 7 a.m. and 3:30 p.m.

And the California Public Records Act is clear: Records are open to inspection during business hours.

I called my editor, and she contacted The Times’ lawyer.

Thankfully, Los Angeles County counsel agreed with us that the ledgers were public records. A week after getting locked out, I was able to set up a time to see the books.

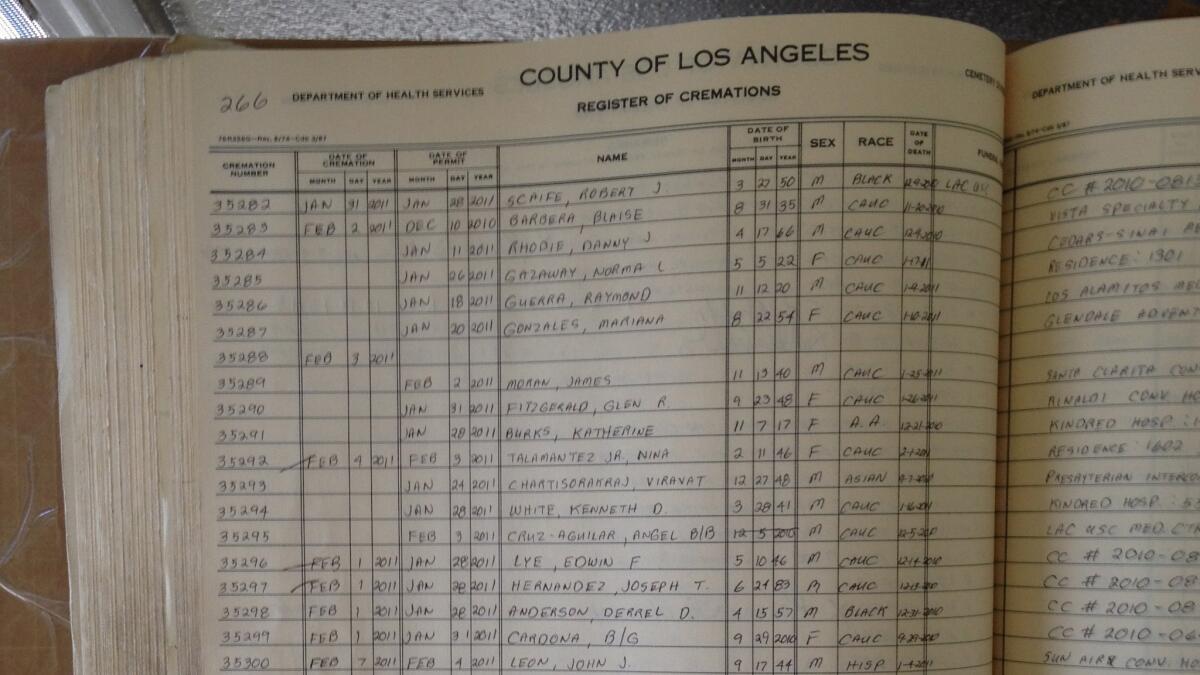

I had hoped that the records would be digital. Instead, I found a large, handwritten book.

So I photographed each page with my iPhone, about 100 on that first visit.

Fellow data reporter Maloy Moore and I eventually decided to focus on the group that would be buried in 2014. They were cremated in 2011.

We opened the photos and started typing. Column after column. Row after row. Each person’s name. And each person’s details.

Sometimes the photos were blurry. Or the edge of the page would curl away from the focal point.

So I reshot those pages. And then we typed more names -- every date, every address, every word was documented. There were more than 1,400 names and details to be recorded.

It took about 10 months of working on it between other projects before we had the completed database. We noted who had died at the hand of another. Counted the number of men and women. Calculated age.

But most important, we had their names.

After we had the spreadsheet, we started to look for curiosities. Who could we find who might have an interesting story? Who might have living relatives?

I compiled a list of “possible people” to pursue.

I knew coroner’s cases, about a third of the group, would be better because I could request the case file and see the details surrounding the death. And see if there had been an attempt to contact next of kin.

One 66-year-old man had an intriguing last name. The coroner’s report said there was no known next of kin. The man died after flipping multiple times in a Pontiac Firebird in the desert near Lancaster. He was wearing a seat belt, according to the report. Two other men in the vehicle were able to walk away from the crash.

Many others, like a 100-year-old woman, didn’t have enough of a trail to follow.

One of the coroner’s reports that I requested was for a man named John Wheelock. I was able to find his son, who said he couldn’t afford to retrieve his father’s ashes. And he couldn’t afford to travel to Los Angeles to pick them up. A mortuary or a family member must retrieve the ashes.

I brought this up with L.A. County Supervisor Don Knabe’s office. Wheelock’s ashes, I am told, will not be buried with the others in December. The county is converting the book into digital form, meaning the names of all the unclaimed dead should be searchanble online in the future.

I hope at least one family member or loved one will see the database and claim the remains before next month. Or, barring that, I hope that people who read the story might pick up the phone and call that estranged sibling to say “hi.” Forget petty arguments. Keep in touch.

We all matter. And we all deserve to be remembered.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.