His flock? Korean and Korean American prisoners written off by their community and, sometimes, their families

- Share via

The Rev. Suk-ki Kim rubs the bleary eyes under his glasses, straining to see the pavement ahead.

It’s not yet 5 a.m. on a Saturday and traffic on Interstate 5 is sparse. A light drizzle is starting to taper off.

After eight surgeries for glaucoma, he can still drive — at least for now — but not in the predawn darkness. This morning, his wife, Kyung-suk, takes the wheel of the minivan.

During a stop, she rifles through a bag of snacks she’s packed for the road trip, fishing out steamed sweet potatoes cocooned in foil and a thermos of hot coffee.

The GPS shows another four hours to Chowchilla, where Valley State Prison rises in the midst of a vast stretch of farmland. For Kim and his wife, it’s a short drive. It’s a breeze compared to the trek to High Desert State Prison in Susanville — 10 to 12 hours with meal breaks — or Pelican Bay, which takes 14.

The pastor and his wife have been making these visits for more than 25 years. They’re regulars at all of California’s 35 state prisons and six federal penitentiaries. They’ve traveled to prisons in Arizona and Texas as well, at times spending nights on a mattress wedged in the back of their minivan along the way.

But the discomfort of a lengthy road trip pales in comparison to the prison life of those they visit: Korean and Korean American prisoners the community, and sometimes their own families, have long since written off. Their time is measured in years, decades, a lifetime.

Which is why the 67-year-old pastor and his wife take to the road most weekends. They talk about God and Gospel, but more often, they listen, as the inmates talk about life, family, anger, regret.

::

Working in the jails and prisons means lots of waiting — hours for visitation, weeks for letters to arrive, months for requests to get approved.

Kim hasn’t always had the patience that is necessary. He arrived in the U.S. from South Korea in 1989 to attend seminary school, after years of a comfortable life working for his family’s manufacturing business.

He believed he’d been called to Southern California to do God’s work, and was eager to get started. After finishing his studies at the Korean American Presbyterian Church Seminary and working as an evangelist for a few years, in 1994 he set up a one-room church in Norwalk and waited for his flock to arrive. But Sunday after Sunday, the room remained deserted, save for his wife and two children.

For a year, he went door to door at homes of people with Korean last names listed in the phone book, hoping to spread the Gospel. He managed to meet one person.

Then a letter arrived from Orange County Jail.

In meticulous handwriting, the inmate, a recent immigrant from Korea who had no friends or family in the U.S., asked the pastor to come pray for him. In the cold, concrete visitation room, Kim held the phone to his ear listening to the man, who was facing a life sentence for rape, tell his life story from the other side of the thick bulletproof glass.

Around the same time, a single mother asked whether the pastor could come to a juvenile court hearing for her son, who had been arrested for theft.

Kim sat in the back of an empty courtroom and watched the mother, trembling, tearfully plead with the judge through an interpreter. The judge turned to Kim and asked who he was. When he said he was a pastor, the judge turned around and buttoned up his shirt out of deference. Then he asked whether Kim had anything he would like to say.

Kim explained that he’d arrived in the U.S. only five years earlier, and was coming to learn of the turmoil and heartache many Korean immigrant families go through as they find their way in a new country.

The judge seemed moved. He cut six months from the boy’s sentence.

The reverend took it as a sign. This was the work he’d been called to do — to minister to those in the Korean community who had gone astray, and to the family members who suffered alongside them.

He named his new prison ministry Onesimus, after the New Testament saint who was an accused thief and runaway slave until he was saved by Paul’s gospel.

::

The minivan speeds past hillsides dotted with cattle, orange groves and cornfields. A billboard by the freeway advertises salvation in giant letters:

Beyond reasonable doubt

JESUS IS ALIVE!

855-for-truth

Throughout the years, it’s been the two of them together on the road. Kyung-suk Kim remembers how terrified she was before meeting an inmate for the first time. But once she started to meet the prisoners face to face and talk to them, the trepidation melted away.

Now, she talks about them as if they are her own children — in addition to their son and daughter. There are inmates she beams about, like the one who managed to get a college degree and get trained as a drug and alcohol counselor from behind bars. There are others whose stories make her ache, like the young man who asked her to persuade his wife to leave him and move on with her life.

About 10 a.m., the pastor and his wife pull into the Valley State Prison parking lot. His phone chimes.

It’s a mother. Her adult son has walked out of the rehab center where he was staying as a condition of his probation, stemming from drug charges.

What do I do if he comes home? she asks the pastor in a shaky voice. This is not the first time. Should she try to convince him to return to rehab? Is the best thing for her son for her to call the police?

“Leave him be for now,” he counsels her. “Because he violated his probation, if you call the police they’ll take him to jail.”

The pastor calmly tells her not to worry too much and gives her the name of a different rehab facility she can direct her son to — he’ll put in a call.

“I know it’ll be painful to send him back, but that’s what’s best for him,” he tells the mother.

The 30 or so members of Kim’s Buena Park church are mostly mothers with children in custody, who came seeking his support. For many of the women, it’s as if they’re serving the sentence along with the child. That shared pain is all the more intense in a culture that considers children more a reflection of their parents than individuals accountable for their own actions.

Many of the mothers have struggled to talk to anyone in their community and even less so at church, where the after-service chatter is usually dominated by parents comparing children’s accomplishments. Thanks to Kim, now the mothers can pray and cry with one another — and even celebrate birthdays together.

The church and Kim’s prison visits were initially funded by operating a thrift store and an alcohol and drug rehab facility; in recent years, it’s supported entirely by donations and an annual benefit concert. For all their work, Kim and his wife earn a combined salary of about $70,000.

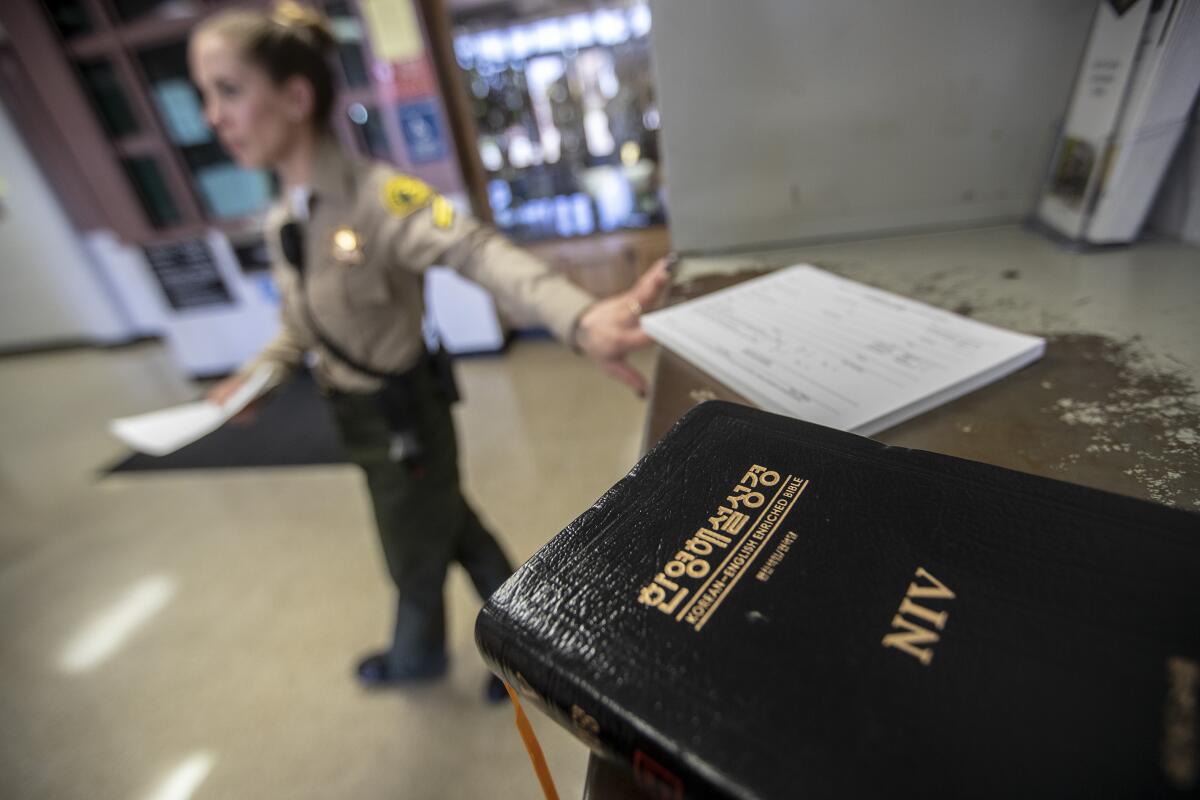

The pastor hangs up the phone and walks into the Valley State Prison lobby, where he’s handed a laminated number.

The wait begins. In a shaded waiting area lined with concrete benches, he paces along a towering wire fence. A sign warns of high-voltage electricity coursing through it.

Back home in South Korea, Kim lived a comfortable life as a CEO running a carpet manufacturing and export business with a personal chauffeur. Kyung-suk was a sheltered housewife who had never worked a day in her life. When Kim was in his late 30s, a bout of illness led him to transform his life.

Starting over again in Southern California was beyond humbling.

For a time, to support their fledgling prison ministry, the pastor and his wife worked as janitors by night. For several years, they reported for work at 5:30 p.m., emptying trash cans and mopping hallways until 4 in the morning. They also peddled clothes at a swap meet to make ends meet.

During the day, he visited inmates, bought them snacks, talked to families, and mailed Bibles to Koreans in custody across the U.S.

When Kim and his wife found out about a young man serving a lengthy sentence for murder at a prison in Susanville, they drove 14 hours through Reno to visit him. He refused to eat the snacks they bought for him and told them petulantly that he didn’t believe in God, that they shouldn’t bother with the Gospel.

But they continued to visit him once or twice a year for the next decade. After 10 years, he told them he was ready for their message.

They became something like surrogate parents to many young men who had turned to drugs and gang life while their immigrant parents were too busy making a living to tend to their children.

Over the years, teenagers became fortysomethings, middle-aged prisoners became elderly. Some became ministers themselves through a correspondence Bible college. Others, who weren’t U.S. citizens, were deported to South Korea after completing their sentences.

For nine years, Kim lobbied the justice ministry in South Korea to allow South Korean nationals in U.S. prisons to serve out their time in Korea; eventually the government agreed. In recent years, he started a ministry and home in Seoul to help those who are deported — many of whom don’t speak Korean — adjust to South Korean society.

At Valley State Prison, a smorgasbord of vending-machine snacks — chicken enchiladas, a fried chicken sandwich, a turkey cheese croissant — grows cold as the inmate talks rapid-fire about what he believes to be the injustice of his case.

It is shortly after noon. Every single chair is taken in the crowded visitation room, which is abuzz with conversation. Children hug their fathers, inmates in blue and navy prison scrubs ravenously dig into the food.

It’s the pastor’s first time meeting the middle-aged man with whom he has been corresponding, a prisoner who is serving an eight-year sentence for sexual battery. He is bald, wearing round horn-rimmed glasses and missing part of an index finger on his right hand — the result of a childhood accident scything hay for cattle in a farm town in Korea, he says.

The pastor listens patiently as the man insists he was unjustly accused by the women who said he touched them inappropriately during a foot massage session.

The inmate has asked eight times for a retrial, to no avail. But during one of his many appeals, his sentence was reduced by more than four years — his release date is now 2025. Even so, he says he is far from done with his efforts to challenge his sentence.

Kim urges the man to eat something. When he finally bites into the vending-machine sandwich, the pastor says: “Laws are made by humans. This world isn’t perfect.”

The pastor speaks of how, for about a decade after arriving in the U.S., he too was saddled with anger and had trouble sleeping. He tells the man about an inmate who served 12 years, never being able to accept his fate and let go of what he felt was an unfair outcome in his case. By the time he served out his sentence and was deported to Korea, he was just skin and bones, Kim says.

“The legal system isn’t about truth; it’s about technicalities,” he says. Justice will come in God’s time, he tells the inmate.

But the man isn’t ready to talk acceptance just yet. He reverts to a monologue about his case. The half-eaten sandwich sits abandoned.

Kim continues to listen, gently nodding along. In more than two decades, he has yet to give up on a soul who didn’t sever contact with him first. The clock nears 3 p.m., when visitation ends. But the pastor’s time stretches far beyond this afternoon, long past 2025.

The wait continues.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.