Thousands more migrant children likely taken from their families than previously disclosed, report says

- Share via

The Trump administration probably separated thousands more children from their families at the border than the roughly 2,700 the government has previously acknowledged, a federal watchdog said Thursday.

The report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General drew the anger of a number of Democrats in Congress, several of whom pledged further investigation into the separations. Sen. Richard J. Durbin of Illinois, the Senate’s second-ranking Democrat, called once again on Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen to resign after the report was released.

“It’s inconceivable that our government chose to secretly separate thousands of children from their parents, was unable or unwilling to reunite these families for months due to incompetent leadership and poor planning, and still doesn’t know how many children were separated,” Durbin said.

Department of Homeland Security officials disputed the inspector general’s estimate.

“We are saying of course separations occurred — but not at the rate of ‘thousands’ they are claiming,” DHS spokeswoman Katie Waldman said in an email.

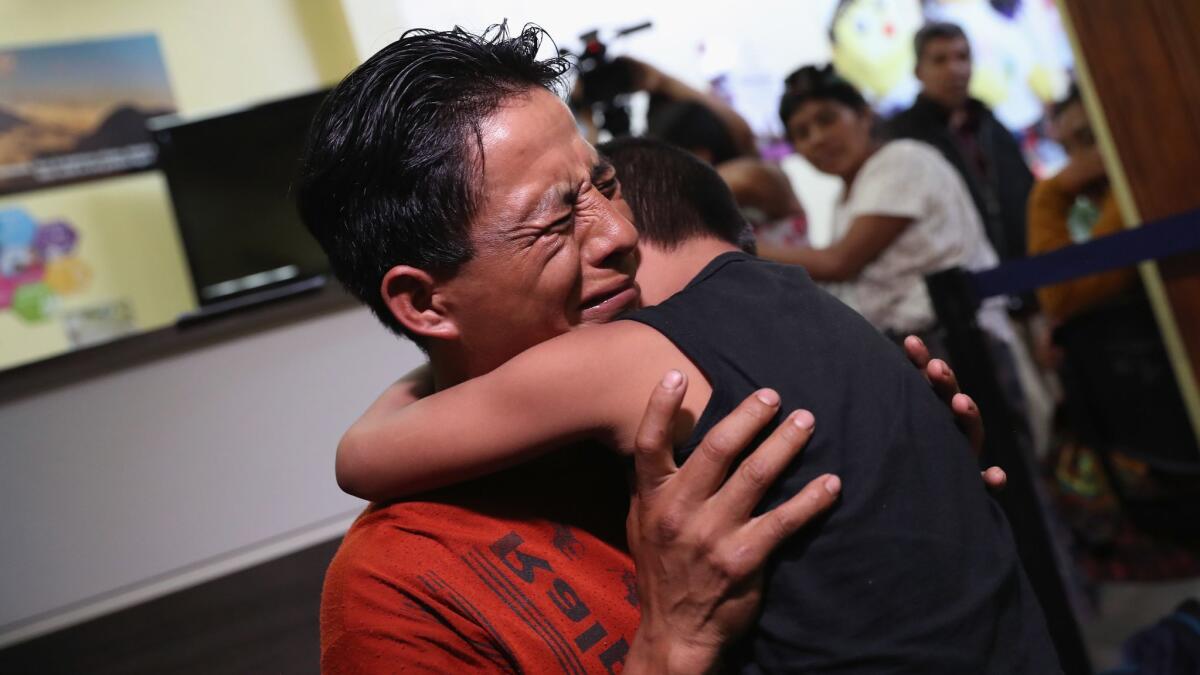

The administration’s practice of separating children from their families at the border — part of its “zero-tolerance” approach to immigration — led to a fierce backlash last year amid reports that children, some younger than 5 years old, were being taken from their parents and placed in government custody.

President Trump eventually signed an executive order ending the separation policy. A San Diego federal court judge also ordered an end to the policy and that families be reunified, a process that proved chaotic as it became clear that officials lacked systems to easily identify and track separated children.

In its efforts to comply with the federal court order, the administration had previously identified 2,737 children separated from their parents.

But Thursday’s report says that number did not include thousands more who may have been separated from their families starting in 2017 and released from government custody prior to the court’s June 2018 order.

The exact number of separated children is still unknown, according to the inspector general’s office.

Homeland Security oversaw the separations while the Department of Health and Human Services was responsible for caring for the children once they were in government custody.

Waldman, the DHS spokeswoman, said children have long been separated from their families in cases in which it is necessary to protect the child.

For “more than a decade it was and continues to be standard for apprehended minors to be separated when the adult is not the parent or legal guardian, the child’s safety is at risk or serious criminal activity by the adult,” she said.

Lynn Johnson, assistant secretary at Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families, said in a written response to the report that the agency’s Office of Refugee Resettlement did “herculean work” to identify separated children and reunify them with their families in response to the court order. She said there was no evidence that the agency had lost track of children in its care.

Johnson also said the department has not tried to determine the exact number of children separated by the Department of Homeland Security prior to the court’s order, citing limited resources.

Undertaking such a count would “take away from ORR’s primary focus on caring for the children currently in ORR care and promptly discharging them to appropriate sponsors,” she wrote.

Even if the agency were to invest in such a count, that would not enable it to “provide any form of relief to discharged children,” she added.

The estimated thousands of additional cases were not included in earlier counts because the court order focused on identifying those who were still in the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement at the time it was issued, the report said.

Health and Human Services officials were unable to give the inspector general’s office detailed information about how children were released prior to the court’s order — whether it was to family, other sponsors or foster care, for example, according to the report.

Most sponsors, however, are parents, legal guardians or other close family members, Health and Human Services officials have said.

Lee Gelernt, the ACLU attorney who led the successful court challenge that resulted in family reunification, said he would ask the federal judge in that case to order the government to explain the numbers in the inspector general’s report.

“We want to know what’s happened to the children so we can make an independent assessment,” Gelernt said.

Although many of the children were probably released to sponsors, “the parent may or may not have signed off on that,” he said.

“Even if the parent did sign off, it may have been because the parent thought that was the only way to get their child out of a government facility,” Gelernt added. “If these parents were coerced or misled into allowing their children to be given to other people and now want their children back they must be given their children back.”

Typically, the vast majority of children in Office of Refugee Resettlement shelters have been unaccompanied minors — those who crossed the border without family.

But officials at the agency began to see a significant spike in the number of children separated from their families in the summer of 2017, as the Trump administration began implementing zero tolerance policies that prioritized the prosecution of immigration offenses, according to the report.

Workers caring for the separated children saw that the new population turning up in government shelters often included very young children. At times, the spike in young children — who had to be placed in specially licensed facilities — resulted in a shortfall in beds for children in the agency’s care, the report says.

After the report came out, several Democrats in Congress pledged to investigate and conduct oversight regarding family separations.

“I’m going to keep working with our new House majority to hold the president accountable for this human tragedy,” said Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-Downey), chair-designate of the Homeland Security Appropriations subcommittee.

Twitter: @palomaesquivel

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.