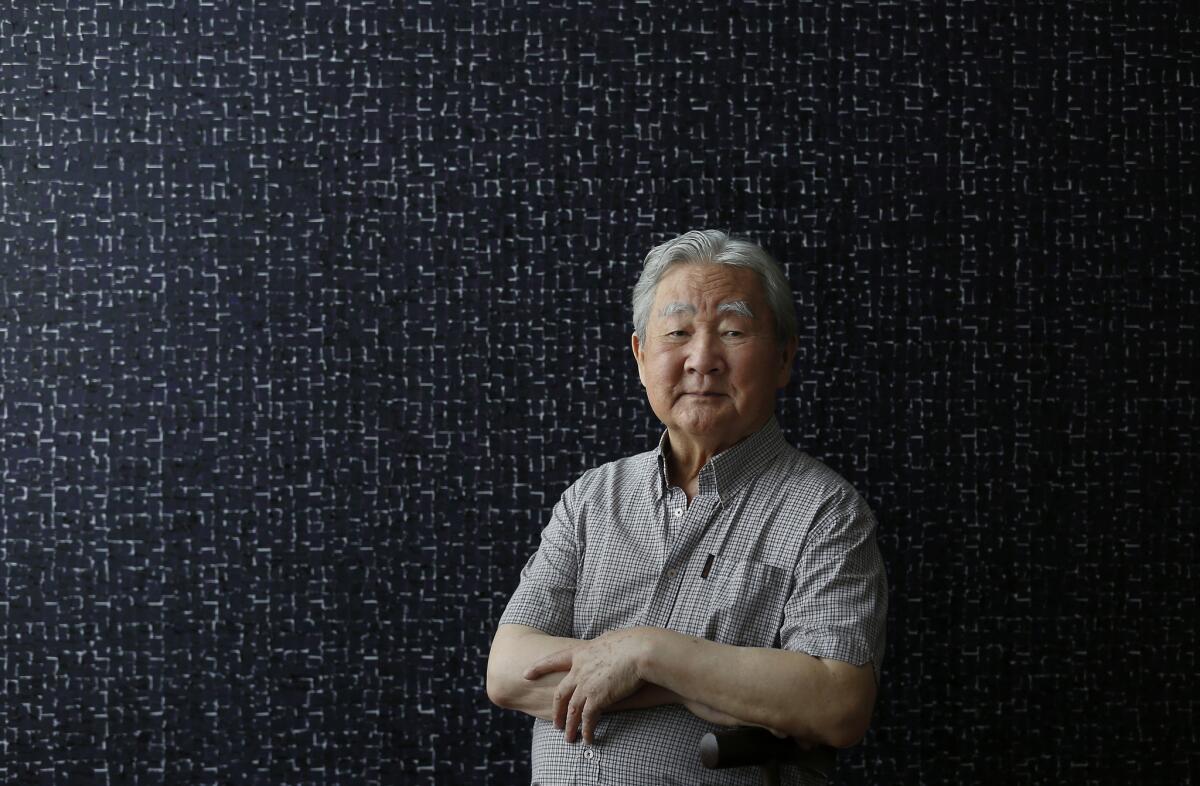

The Pacific has been filling Young-il Ahn’s canvases for decades. At 83, the L.A. artist is getting belated recognition.

- Share via

In the summer of 1983, artist Young-il Ahn set off in a rented dinghy toward the horizon.

The painter frequently sought solace in the waters between Santa Monica and Catalina Island, taking only a fishing rod and sketchbook. That day, he was soon enveloped in fog so thick he couldn’t see an inch in any direction.

A crushing fear set in, and the fog felt like a heavy weight on his chest. He turned off the engine and left his fate to the waves.

Then in an instant, the ocean revealed itself in all its colors — like pearls of all shades scattered as far as the eye could see. In a moment at once rapturous and humbling, Ahn felt himself a part of the ocean, the ocean a part of him.

He’s been painting what he saw in that instant ever since, calling his evolving body of work the “Water Series.” They are canvases of all sizes filled with meticulous square knife strokes that leap off the canvas like waves — at once still and dynamic, monochromatic and iridescent.

Now, at age 83, the Korean American artist is getting recognition after half a century of relative obscurity in his adopted home of Los Angeles.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is showcasing Ahn’s “Water Series” in its first solo exhibition of works by a Korean American artist, and on Friday, the Long Beach Museum of Art will open a 35-year retrospective of his paintings. High-profile galleries are featuring him in Seoul, where his works are in great demand.

The acclaim has changed little of Ahn’s days.

Today, as he has for decades, he sits in front of a canvas in his studio, a converted furniture factory near the 10 Freeway where the air is rich with the scent of spike lavender oil he uses to thin paint. He steadies the right hand impaired by a stroke, subtly tilts his head left and right like a bird, and takes his painting knife from palette to canvas, palette to canvas.

And once more the Pacific bubbles up before him.

Born in prewar North Korea, Ahn was a prodigious child who painted and drew throughout his childhood in Japan and South Korea.

He studied art at the nation’s premier Seoul National University. Art materials were so difficult to come by that he and other students resorted to cloth used to wrap dead bodies in lieu of canvases. Yet he always found a way to paint.

Ahn won national awards and was a darling among foreign collectors in postwar Seoul. Even so, he grew eager to get out from the shadow of his father, a painter and art professor.

He and a handful of artists left South Korea when it was still a dirt-poor nation that was mostly sending miners and nurses abroad to earn foreign currency.

“They came at a time when people would have asked, ‘What’s Korea? Where is Korea?’” said Virginia Moon, a curator at LACMA.

“They were rebels, these harabojis,” she said, using the Korean word for “grandpa.” “They came here to map their own ground.”

With an invitation from an American lawyer who had purchased one of his paintings, Ahn boarded a plane for Hawaii in 1966. After traveling in Hawaii and a brief stay in Laguna Beach, he went to New York, where a few of his compatriot artists had settled.

New York was exciting, but it wasn’t for Ahn. A lifelong fisherman, he relishes silence. After eight months, he came to Los Angeles, a place that would both inspire and entrance him, and serve as the backdrop to his darkest moments.

He rented an apartment in 1967 at the corner of Pico Boulevard and Spaulding Avenue and took his paintings to the nearby row of galleries dotting La Cienega Boulevard. The first one he walked into, Zachary Waller, wanted to sign him to exclusively sell his works.

He thought he misunderstood because of his still elementary English. But the gallery was serious, and by the next day, his piece had already sold. He signed a 10-year deal with the gallery. Soon he brought over his wife and three daughters from Korea.

Over the next three years, Ahn’s career was off to a promising start. He painted beach scenes, the harbor, Lake Isabella, the sunset over San Pedro, and the colors of California.

Moon, the LACMA curator, said many other Korean diaspora artists of his generation were often inspired by their yearning for their homeland.

“Young-il never did that. That’s why his view and his paintings are all very California. They are very Los Angeles,” she said.

His work started getting noticed. A Christian Science Monitor critic wrote in 1969 that Ahn was “one of Korea’s foremost young painters.”

“Korean Young-il Ahn composes grids of pale, neatly puttied color, often sensitive arrangements but diluted by cute scenes; cows, children, cityscapes and umbrellas in the rain,” an L.A. Times gallery guide the same year noted.

His view and his paintings are all very California. They are very Los Angeles.

— Virginia Moon, LACMA curator

Hee-Jin McClain, the youngest of Ahn’s three daughters, says her memories of her father are mostly of him in the studio. She’d sit doing her homework; he’d hum as he painted.

When he wasn’t painting, he was playing the clarinet or piano, later teaching himself the cello. In the evenings, he listened to Vin Scully and Chick Hearn call Dodgers and Laker games, respectively, on the radio.

In 1970, a lawsuit brought his career to a halt. Stanley Hietala, an early benefactor he had met in Seoul who lived in Laguna Beach, sold Ahn’s works unbeknown to the gallery or the artist. The gallery sued Hietala, and all sale of Ahn’s works were frozen.

It would be a decade before the litigation fizzled to an end. By then, the gallery was broke, Hietala had moved out of state and Ahn was left in financial ruin and a deep depression.

He filed for bankruptcy, and his wife, whom he’d met as a fellow art student, started working as a manicurist. His marriage fell apart, and he moved alone to a downtown studio where he lived for years without a phone. In the throes of a deep depression, he slashed hundreds of his paintings.

Susan Baik, a gallerist who has been working in L.A.’s Koreatown since 2002, first heard of Ahn a few years ago from a client interested in buying one of his works.

By the time Baik met Ahn, he’d suffered a massive stroke in spring 2013 that affected the right side of his body, leaving in doubt his ability to continue painting. She visited his studio, filled with canvases he’d painted over the years.

“I felt like I walked into an untouched cave with all these gems,” she recalled.

She wanted the world to see what she saw in Ahn’s studio. Earlier this year, she and her husband donated funds for LACMA to acquire one of Ahn’s paintings from the “Water Series.” The acquisition was announced shortly before the opening in February of “Unexpected Light” — 11 paintings from the series that will be on display until January.

Among the paintings is “Water A-14,” the first work he painted eight months after his stroke. His wife Soraya, a novelist and children’s book author he married in 2001, said he insisted on testing himself with a 90-by-80-inch canvas to see if he could still paint. He’s had to make concessions. He gave up going up ladders after he fell, and hired a carpenter to stretch out his canvases.

Sitting in Ahn’s studio on a recent Tuesday, Soraya muses out loud if recognition and success would have come decades earlier had he remained in New York, with its ’60s art scene, as a young artist.

Ahn, a man with wild eyebrows and few words, smiles and nods. The mid-morning California sun filters into the brick-walled studio, gently lighting his canvases.

“New York beaches are too cramped,” he finally says.

For more California news, follow me on Twitter @vicjkim

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.