Must Reads: Some L.A. streets aren’t being repaved because of a law dating from the Depression

- Share via

Bob Carter has long complained to the city about the cracking road that winds along the green slope near his Woodland Hills home.

“They put me off for years,” Carter said.

Dozens of people once signed a petition pleading for Los Angeles city crews to repave the short and shabby stretch of San Miguel Street, saying it was dangerous. Another neighbor is now suing the city, complaining that water rushing through gaping cracks in the street caused an estimated $400,000 in damage at her property downhill.

Neighboring streets have been repaved, but not the bulk of San Miguel, where the pavement is so broken it looks like alligator skin.

The reason? The road was “withdrawn” from public use more than eight decades ago, officials said.

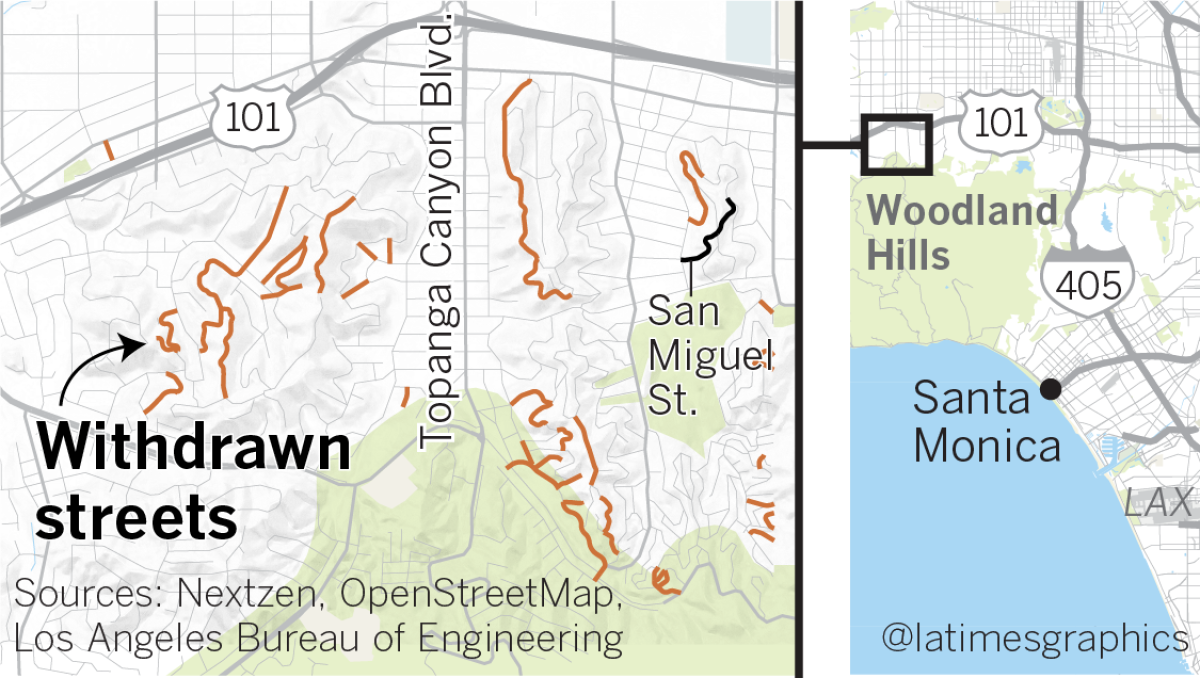

San Miguel is one of more than 200 streets that were officially withdrawn under an ordinance passed during the Depression, when Los Angeles said it didn’t have enough money to fix dangerous streets. At the time, city engineers warned that hillside banks on San Miguel and other Woodland Hills streets were sliding and blocking traffic.

A scattering of hillside roads from the Hollywood Hills through the San Fernando Valley were pulled from service.

Other roads in Los Angeles were withdrawn in the decades after because they were not up to city standards, were prohibitively expensive to maintain or were a magnet for “boisterous or criminal activities,” according to engineering bureau reports from 1986 and 1988.

In one case that went to court, residents in a Hollywood Hills neighborhood got roads withdrawn in 1985 and erected gates to try to stave off crime and graffiti.

In some instances, city records indicate, private or homeowner groups agreed to maintain the withdrawn streets instead — and some were gated off entirely. But in Woodland Hills, many withdrawn streets seem just like other roads in the rolling hillsides, lined with houses and regularly traveled by motorists, and no one else has taken over their upkeep.

Some have still not been reinstated decades later, despite complaints from residents. And as the city has trumpeted increased funding to fix its worst roads, such streets have been left out. City officials say Los Angeles does not even assign them a letter grade ranging from A to F — the key measure the city uses to gauge the quality of its sprawling network of streets.

“This is bizarre,” Councilman Joe Buscaino said at a City Hall hearing about the issue 3½ years ago, chuckling in disbelief. “Who’s been maintaining these streets the last seven decades?”

The Bureau of Street Services said city crews will fill potholes and make other “minor repairs” on such streets but will not repave them.

The short stretch of San Miguel has gotten a new asphalt curb, had some potholes filled and appears to have undergone some stabilization work in the past, based on photos supplied by residents. But most of it has not been resurfaced, save for an intersection with another Woodland Hills street that is not out of service.

City officials declined to confirm exactly what work has been done on San Miguel because of the ongoing lawsuit, but they said besides that intersection — which was resurfaced as “part of normal maintenance” — the withdrawn stretch of San Miguel had not been repaved.

After residents raised concerns about San Miguel four years ago, a Bureau of Street Services engineer told council aides that the city had “minimal” responsibility for maintenance on such streets and that “we are only required to keep the roadway passable,” emails obtained by residents show.

When L.A. first moved to withdraw the streets, a city engineer told lawmakers that it would prevent possible claims against the city for damages arising from defective streets, archival records show. The 1936 decision came one year after California introduced a new statute allowing cities to pull “municipally owned or controlled property” out of public use.

That state code has since been repealed. And in the decades since, city attorneys have advised that L.A. still bears legal responsibility for such damages on withdrawn streets, according to city records, including a 1988 engineering report and a 2014 motion made by a city councilman. The city attorney’s office said it could not comment on confidential advice given to its client.

Such streets were supposed to be outfitted with barricades and warning signs, according to the original ordinance. But on San Miguel, the only sign of its obscure status is the seam between the crumbling street and the smoother pavement leading up to it.

Members of the public were supposed to be barred from using withdrawn streets, but city officials said they knew of no cases in which anyone has been prosecuted.

Thirty years ago, The Times reported that a phalanx of orange warning signs suddenly went up on streets that snaked through canyons in West Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley, perplexing residents who had no idea that their streets had ever been withdrawn.

At the time, one Woodland Hills resident told the newspaper that similar signs had gone up in his neighborhood a decade earlier, then abruptly disappeared without explanation.

Many residents have no idea that their street is withdrawn until they try to get it fixed, said Councilman Bob Blumenfield, whose district includes Woodland Hills.

“This whole thing is kind of crazy,” Blumenfield said.

“The reality is, whether we like it or not, we’re liable for these streets anyway,” he added.

Blumenfield has asked city staffers for a report that would list all the withdrawn streets, detail how the city decides whether they can be reinstated, and spell out what resources it will take to assess repair costs. The City Council approved that request in March.

Decades ago, city staffers told lawmakers that such streets needed to be up to city standards — including curbs, gutters and other features to handle drainage, and pavement thick enough to withstand three or four decades of use — in order to be reinstated. But under the original 1936 city ordinance, L.A. can return withdrawn streets to public use whenever they are deemed “safe and passable.”

Blumenfield said that four years ago, when he first asked about reinstating all the streets in his council district that had been withdrawn during the Depression, he got pushback from city officials who said it would take “enormous resources” to even figure out what that would take. So instead, the councilman said, he tried to start reinstating them one at a time.

Nine roads in his district have been reinstated after city officials reexamined them, and more are on the way, according to Blumenfield aides.

But when Blumenfield first proposed reinstating San Miguel, city engineers found that an erosion gully had formed down the slope and recommended restoring the hillside. Council aides have also said that the short stretch of San Miguel is not as wide as it is supposed to be, which could complicate fixing it in the future because some neighbors have built near the street. Lawmakers can, however, approve street-by-street standards allowing narrower roads.

All in all, “San Miguel has a unique set of circumstances that has been problematic,” Blumenfield spokesman Jake Flynn wrote in an email, adding that the lawsuit “severely limits what we can say about the situation.”

Years of back-and-forth over the broken street have aggravated neighbors like Bobbie Wasserman, who said that last year a storm triggered a downpour like Niagara Falls from the roadway into her yard downhill, swamping it with mud and cracking retaining walls. In September, she filed suit against the city, complaining that the damage was caused by the shoddy state of the road.

At a recent community meeting in Woodland Hills, she lamented that trying to get the street fixed was like being on a hamster wheel. Wasserman said city officials had given shifting explanations about what it would take to reinstate San Miguel, even as the city made other fixes they had been told were needed to bring it back.

Her neighbor Doug Litten chimed in, arguing that other withdrawn streets had been repaved “without rhyme or reason,” pointing to the smooth surface of other out-of-service streets in the area.

The Times confirmed with the Bureau of Street Services that some withdrawn streets in Woodland Hills have been repaved, but the department was unable to quickly determine exactly why. Bureau spokeswoman Elena Stern said that although its policy is not to resurface those streets, withdrawn roads might be “semi-improved” because of a lawsuit or when discretionary funds become available.

“It’s this constant barrage of excuses,” Wasserman said one afternoon.

“Whatever they need to do to maintain it,” she said in frustration, “they just need to do it.”

Times staff writer Ben Poston contributed to this report.

Twitter: @AlpertReyes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.