Nobel Prize-winning Caltech scientist Ahmed Zewail has died at 70

- Share via

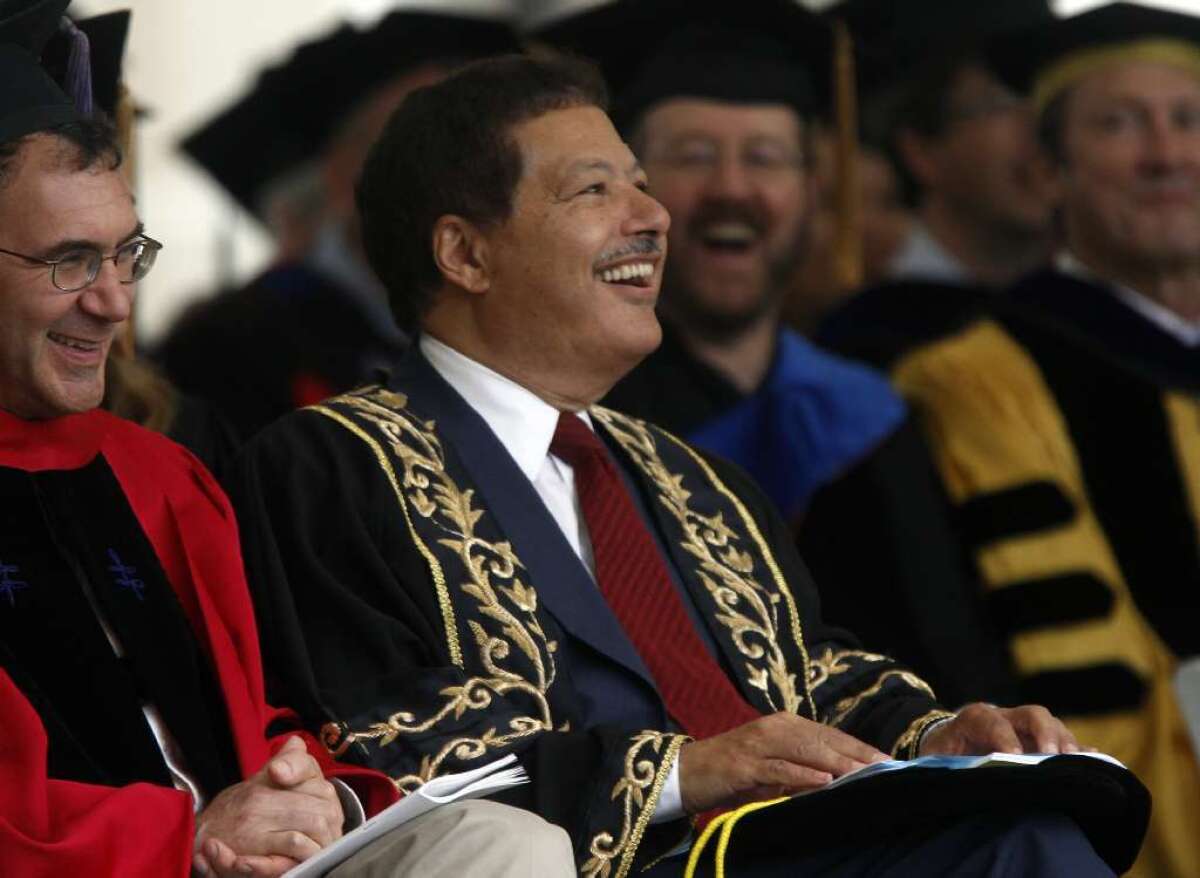

Ahmed H. Zewail, a Caltech chemist who won the 1999 Nobel Prize in chemistry for using lasers to reveal the secrets of chemical reactions, died Tuesday. He was 70. The cause was not disclosed.

The American chemist was the first Egyptian and Arab to win a Nobel in science.

Well-known in Egypt, Zewail was also an outspoken voice for progress in the aftermath of the 2011 protests in Tahrir Square.

“He had these three fundamental principles of wisdom, the first one being passion, the second one being hard work and the third one being optimism,” his son Hani Zewail said.

Zewail was born Feb. 26, 1946, in Damanhur, near Alexandria. As a child growing up in nearby Desuq, he was drawn to science and engineering and amused himself by solving complex physics problems. He became intrigued by what he called the “mathematics of chemistry” and tried to reproduce the phenomena he saw in the lab at home.

“In my bedroom I constructed a small apparatus, out of my mother’s oil burner [for making Arabic coffee] and a few glass tubes, in order to see how wood is transformed into a burning gas and a liquid substance,” he recalled in his Nobel autobiographical statement. “I still remember this vividly, not only for the science, but also for the danger of burning down our house!”

After he finished his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Alexandria University, Zewail’s professors encouraged him to look abroad to pursue his PhD. This was easier said than done: In the wake of the 1967 war between Israel and several Arab states, Egypt did not offer financial support for its citizens to study in the United States.

Zewail cast about, corresponding with several universities. The University of Pennsylvania finally offered him a scholarship.

“Arriving in the States, I had the feeling of being thrown into an ocean. The ocean was full of knowledge, culture and opportunities, and the choice was clear: I could either learn to swim or sink,” Zewail recalled. “The culture was foreign, the language was difficult, but my hopes were high.”

In 1974 he moved to UC Berkeley for postdoctoral research and joined Caltech as an assistant professor two years later. He remained at Caltech for the rest of his career.

The chemical reactions he studied are not just simple equations. Between starting chemicals and final products, fleeting chemical intermediates are born and die. These reactions happen so quickly that for years scientists thought it would be practically impossible to catch them in action.

But Zewail found a way to document what amounts to an intricate atomic dance. He developed very fast flashing lasers capable of catching atoms interacting at various stages in reactions. The pulsing lasers allowed him to study chemical processes on almost infinitesimally small timescales.

“One of the very special things about Ahmed was he had this intuitive sense about that dance ... of the choreography of how a chemical reaction occurs,” said Jacqueline Barton, chair of Caltech’s division of chemistry and chemical engineering and a friend of Zewail’s.

Researchers later used this technology to explore the molecular secrets of photosynthesis and the photochemical processes involved in night vision. It has also been used to design catalysts for generating renewable solar fuels.

In recent years, Zewail had been working on four-dimensional ultrafast electron microscopy. Scientists say the technology will allow them to see the atomic-scale behavior of materials through space and time.

Zewail garnered a slew of scientific honors besides the Nobel. He was awarded the Order of the Grand Collar of the Nile in Egypt, the Order of Légion d’Honneur in France, and the Priestley Medal, the American Chemical Society’s highest honor.

He served on President Obama’s science and technology advisory panel from 2009 to 2013 and as the president’s special envoy for science to Middle East.

Zewail was admired in Egypt, where a research institute, the Zewail City of Science and Technology, is named after him. He cared deeply about the country and worried about its future, said his daughter Maha Zewail-Foote, a chemistry professor at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas.

In a 2013 op-ed in the New York Times, Zewail called on Egypt’s leaders to protect education and science from political feuds.

“A part of the world that pioneered science and mathematics during Europe’s dark ages is now lost in a dark age of illiteracy and knowledge deficiency,” he wrote.

He also called on the U.S., which at the time gave about $1.5 billion per year in aid to Egypt, to ensure that more resources went to education and research.

“Any group hoping to authentically represent the hopes of the Egyptian people must make educational attainment and economic growth its priority,” he wrote.

Zewail lived in San Marino, Calif. Besides his son and daughter, he is survived by his wife, Dema Faham, and another son, Nabeel, and daughter, Amani.

ALSO

Anne of Romania, wife of King Michael, dies at 92

James Alan McPherson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, is dead at 72

David Huddleston, who played the title role in ‘The Big Lebowski,’ dies at 85

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.