Alan Wood dies at 90; provided Iwo Jima flag in World War II

- Share via

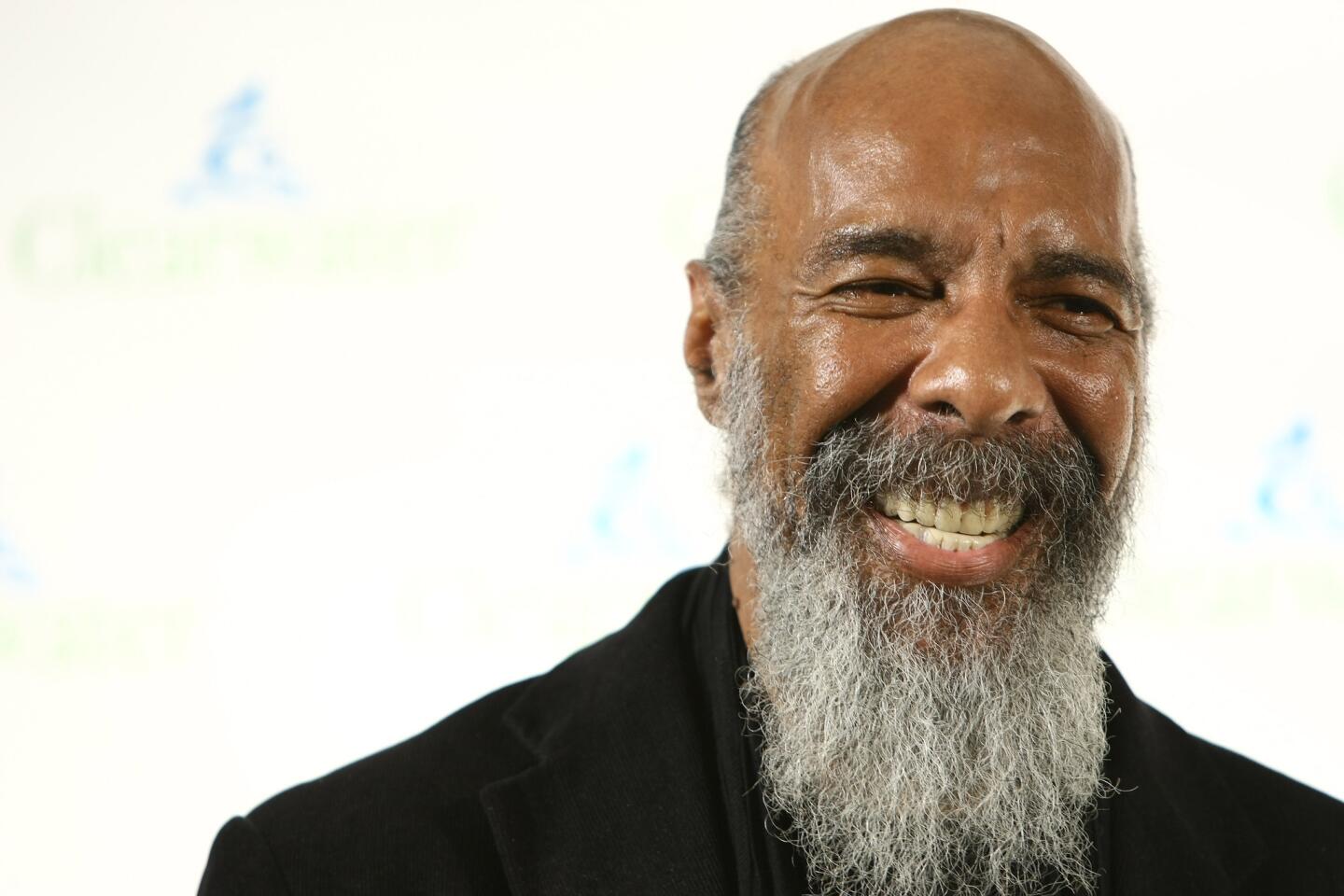

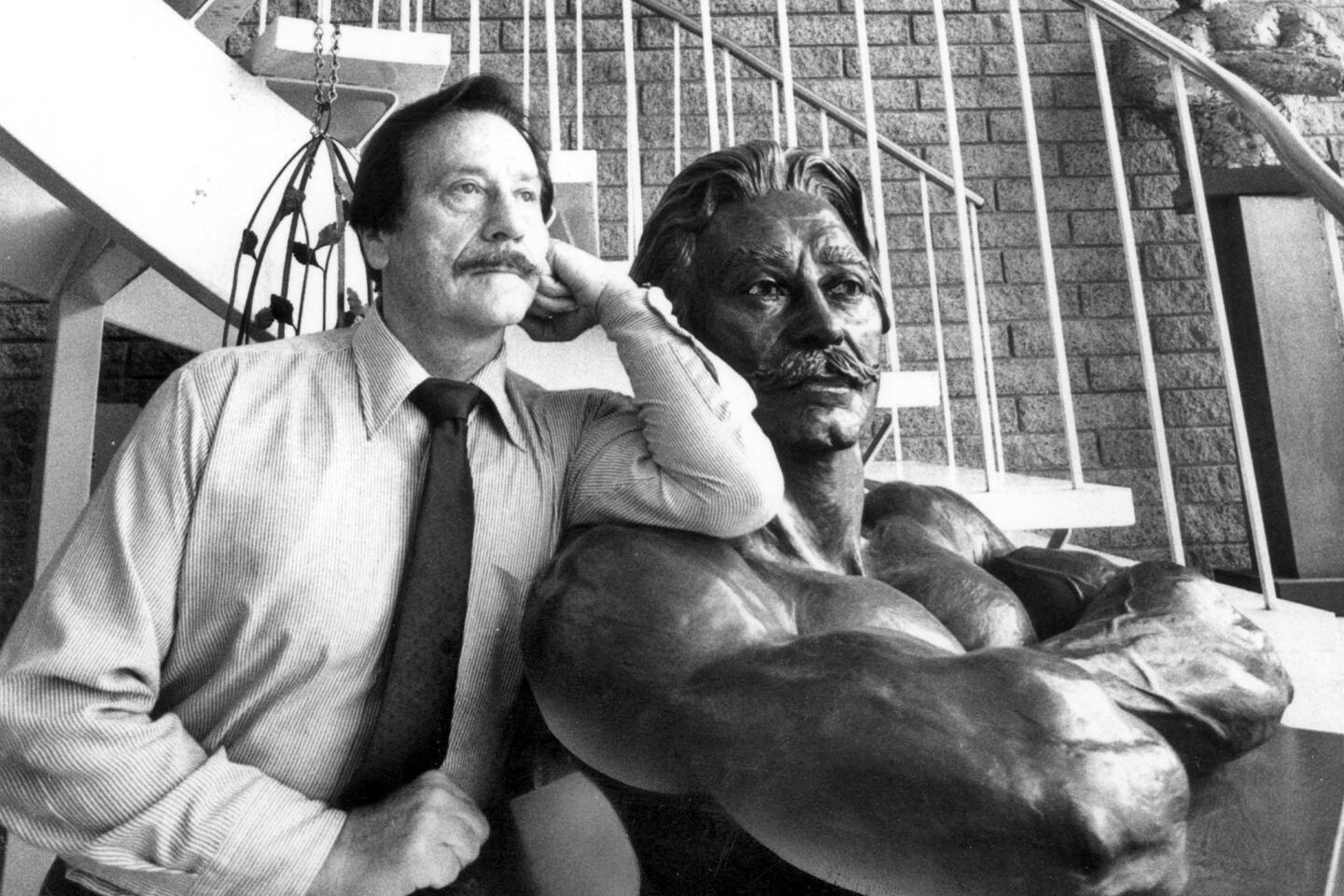

Alan Wood never claimed to be a hero, but he did play a supporting role in one of World War II’s most stirring moments.

It was at Iwo Jima on Feb. 23, 1945. Straining into the wind, five Marines and a Navy corpsman planted the Stars and Stripes on the rocky peak of Mt. Suribachi. As the flag unfurled, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal captured what may have been the war’s most iconic image, a shot that inspired monuments and made the Iwo Jima flag-raisers instantly famous.

Wood, a 22-year-old Navy officer, wasn’t among them. But it was Wood who provided the flag — a small act that would always remind him of the epic sacrifices made by so many on that desolate island 750 miles south of Tokyo.

“The fact that there were men among us who were able to face a situation like Iwo where human life is so cheap, is something to make humble those of us who were so very fortunate not to be called upon to endure any such hell,” he wrote in a 1945 letter to a Marine general who asked for details about the flag.

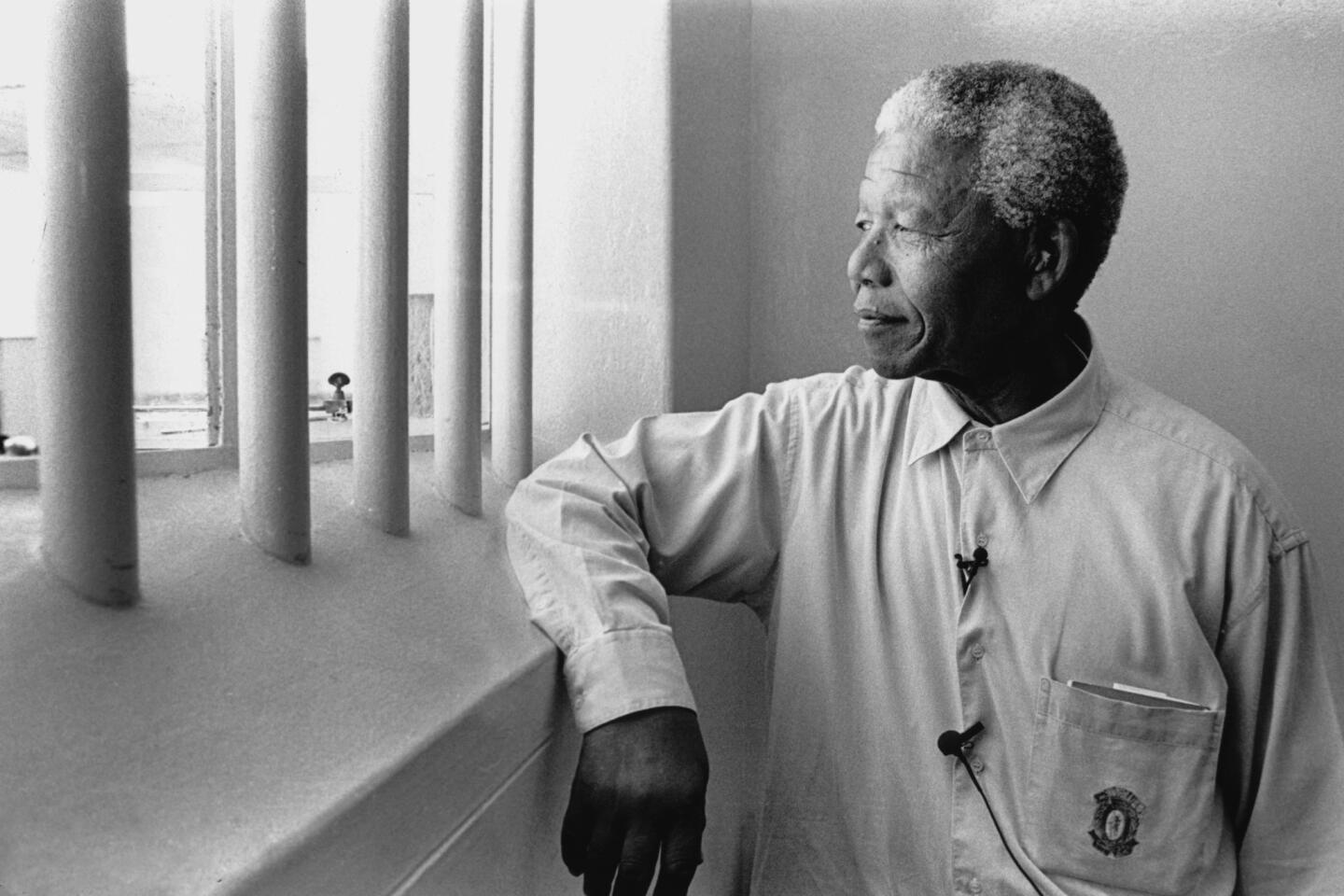

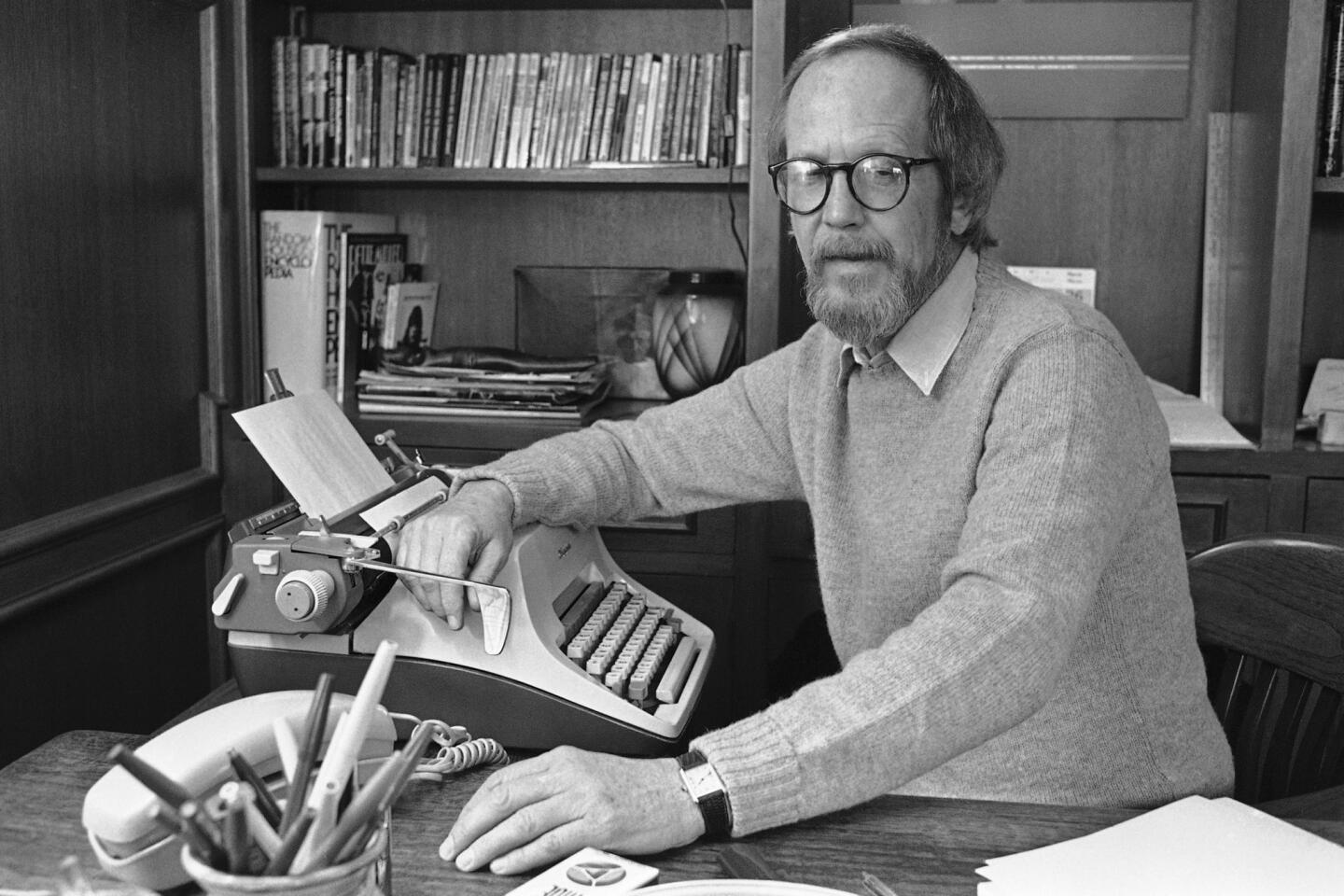

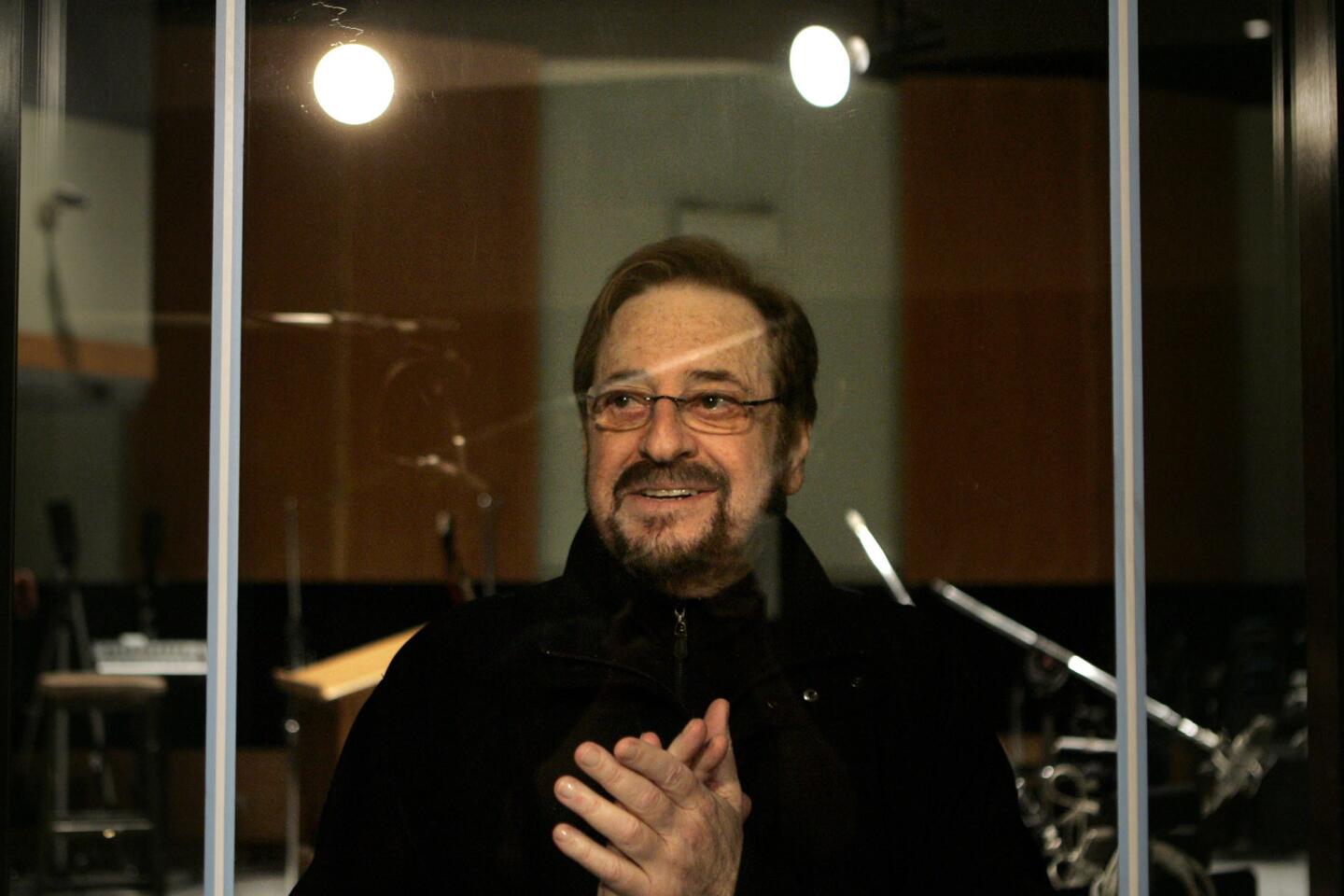

Wood, who went on to spend nearly five decades as a technical artist and public information officer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, died April 18 at his Sierra Madre home. He was 90 and had congestive heart failure, his son, Steven Wood, said.

Wood was in charge of communications on LST-779, one of many landing ships that disgorged tanks and construction equipment on Iwo Jima’s shores. Beached close to the base of Mt. Suribachi, his ship was boarded one morning during the five-week battle by a tired Marine seeking the biggest flag he could find.

After heavy fighting, U.S. forces had managed to scale the 500-foot peak and hoist an American flag from a length of blasted water pipe. But top U.S. officials on the island called for a larger flag — perhaps, according to some accounts, because Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, who was witnessing the battle, asked for the first one as a memento.

Wood gave the young Marine a 37-square-foot flag he had discovered months before in a Pearl Harbor Navy depot. That was the flag whose raising was photographed by Rosenthal in what the 1945 Pulitzer Prize committee called “a frozen flash of history.”

As for Wood, a lieutenant junior grade by the end of the war, “he didn’t talk much about it,” his son said. “He didn’t draw attention to himself. He was just there when someone needed a flag and he gave it to them.”

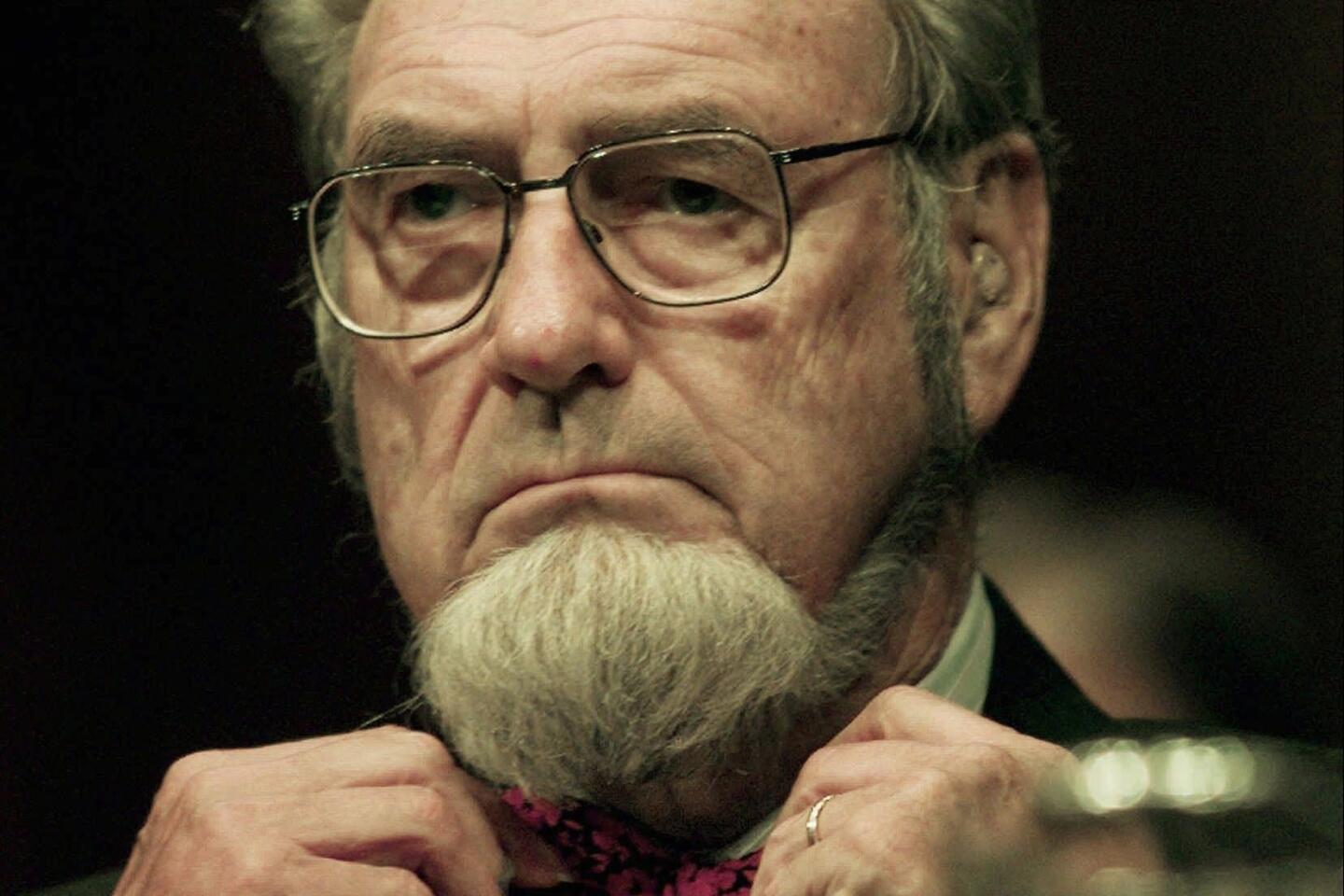

Over the years, others have claimed that they provided the flag, but retired Marine Col. Dave Severance, who commanded the company that took Mt. Suribachi, said this week in an interview that it was Wood.

“I have a file of more than 60 people who claim to have had something to do with the flags,” he said from his home in La Jolla.

About 6,800 U.S. troops died on Iwo Jima’s eight square miles. Japanese losses were estimated at more than 20,000.

Born in Pasadena on May 3, 1922, Alan Stevenson Wood came from one of the Sierra Madre area’s pioneering families. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history at UC Berkeley. A talented watercolorist, he studied at the Art Center in Pasadena before joining JPL in 1958.

As a spokesman for the lab, he helped coordinate news coverage of the Mariner, Viking, Voyager and Galileo spacecraft missions.

Active until his final years, he drove an RV to a former colleague’s wedding in Wyoming when he was 87.

Wood’s wife, Elizabeth, died in 1985. He is survived by his son Steven of Solana Beach and three grandchildren.

A memorial service is scheduled for 11 a.m. Saturday at Sierra Madre Episcopal Church of the Ascension. Burial will follow at Sierra Madre Pioneer Cemetery.

The flags of Iwo Jima are on rotating display at the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Triangle, Va.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.