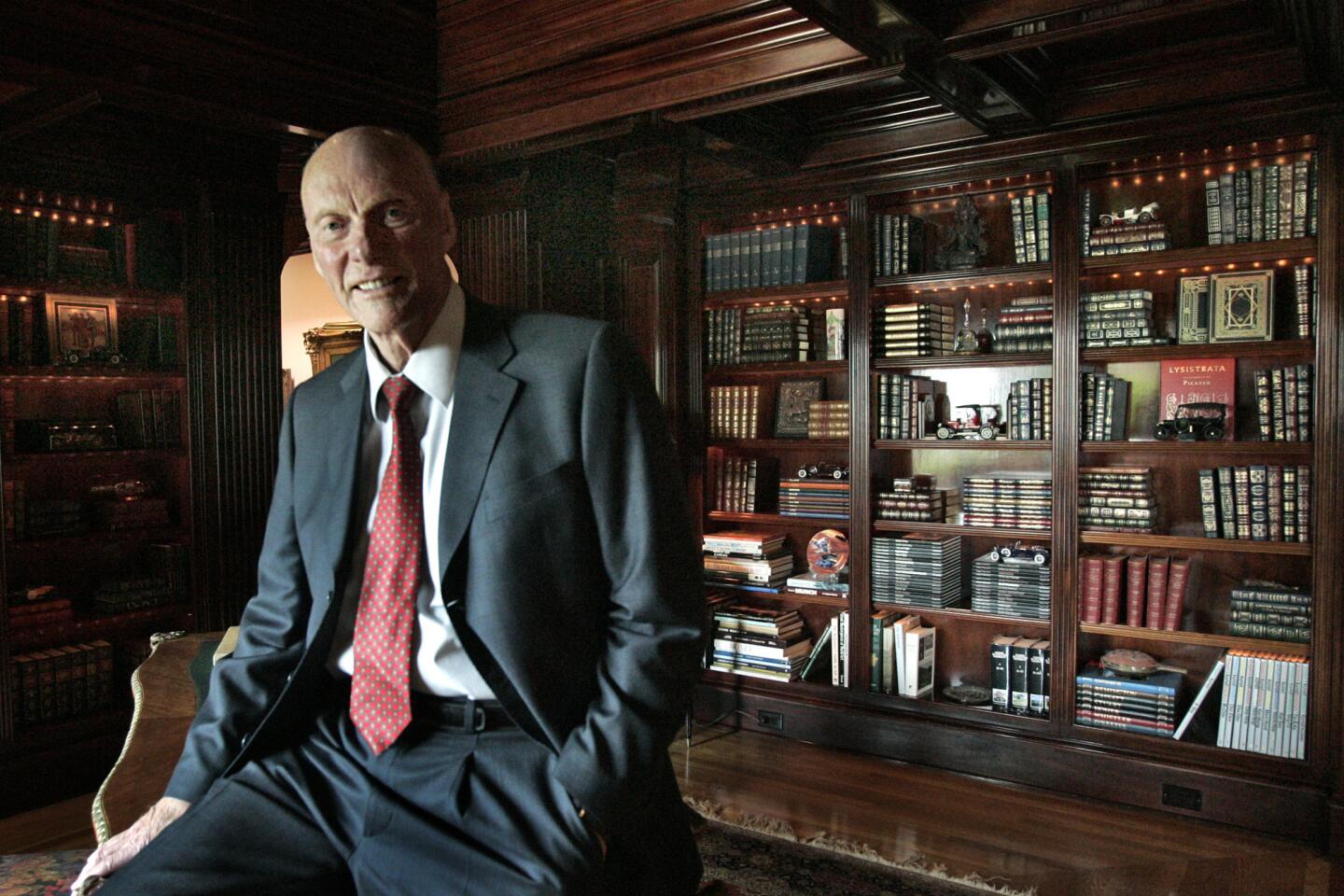

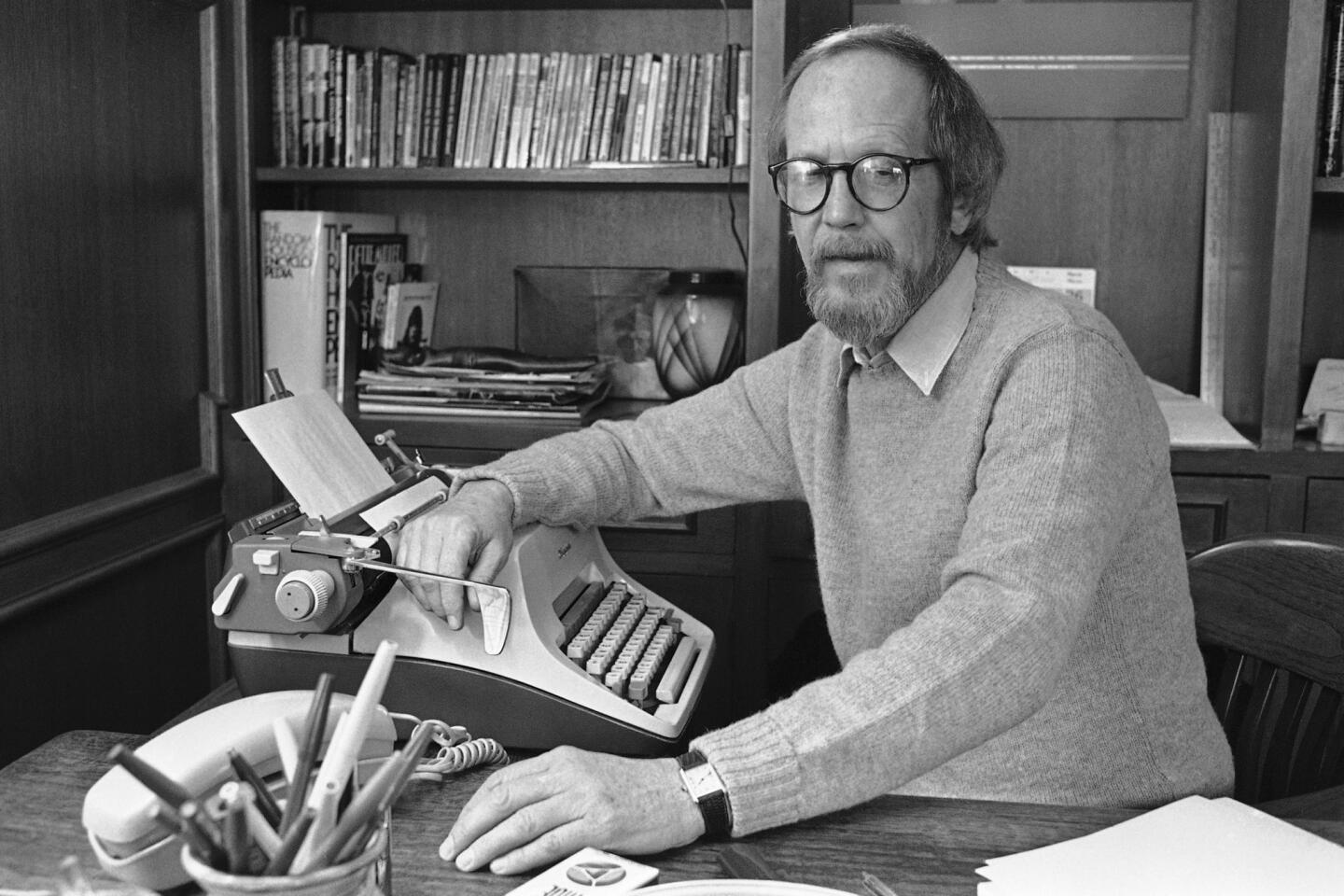

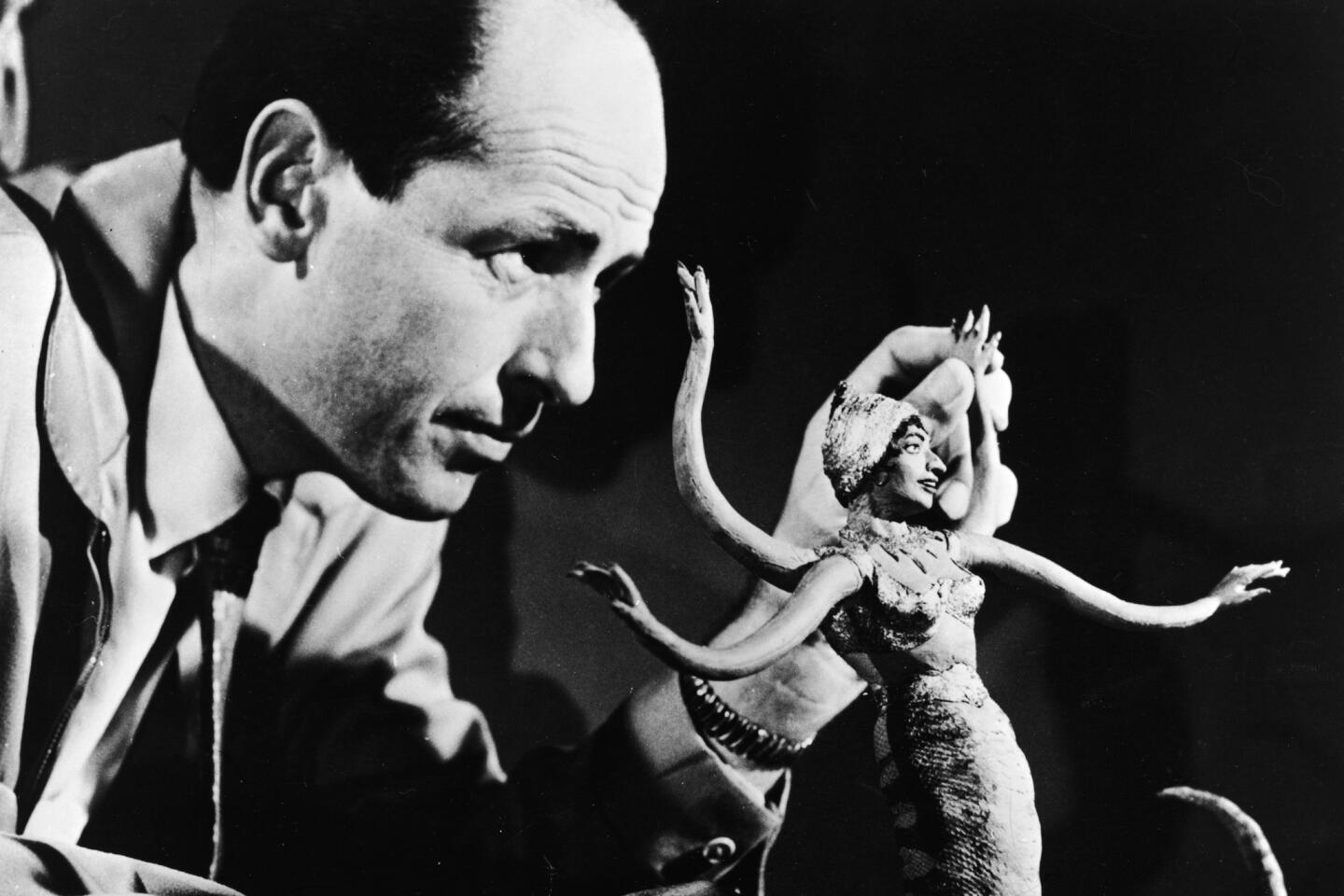

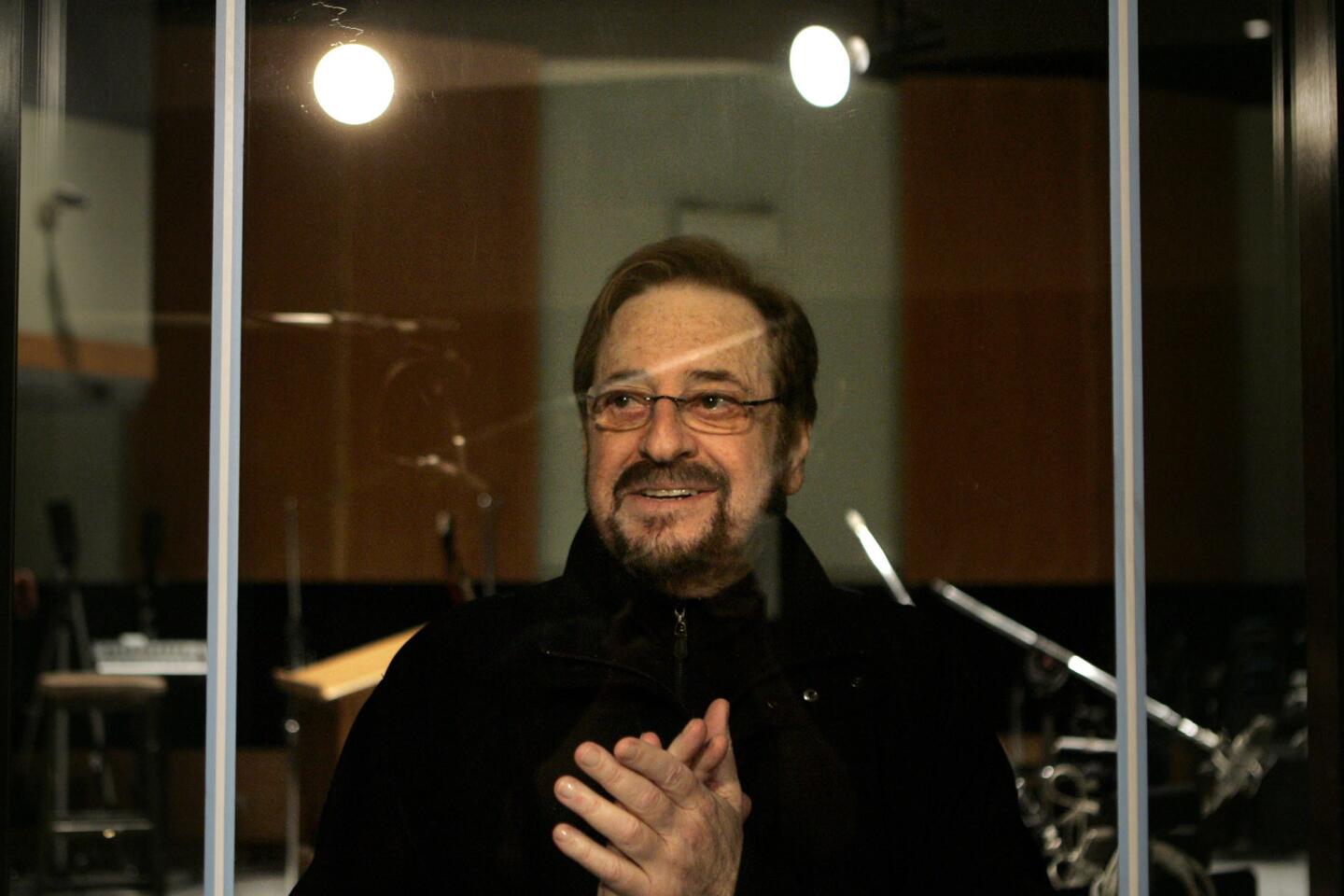

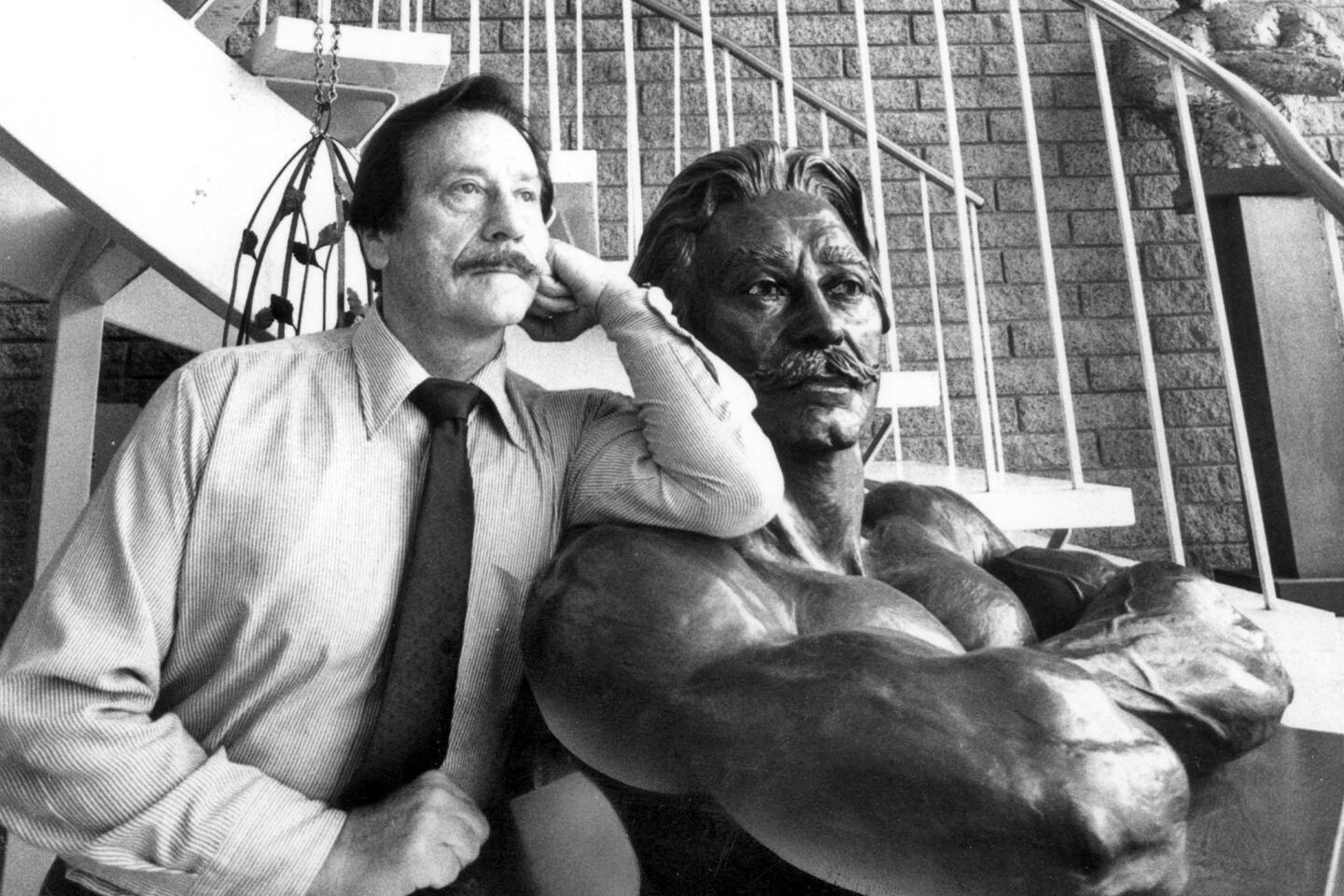

Allan B. Calhamer dies at 81; inventor of Diplomacy game

- Share via

The origins of the board game Diplomacy can be traced to an old geography book that Allan B. Calhamer discovered while rummaging around with a friend in the attic of his boyhood home in suburban Chicago.

Calhamer was fascinated by the exotic countries and old boundaries laid out in the book, places like the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire.

The final inspiration came at Harvard, when Calhamer read Sidney Bradshaw Fay’s “The Origins of the World War” during Fay’s class on 19th century Europe.

“That brought everything together,” Calhamer told Chicago magazine in 2009. “I thought, ‘What a board game that would make!’ ”

After being rejected by several game companies, Calhamer published 500 copies of Diplomacy in 1959. The game came to develop a devoted following around the world.

“He was such a character, brilliant, but never in an arrogant way,” Selenne Calhamer-Boling said of her father. “He just had his own way of doing things.”

Calhamer, 81, died Feb. 25 at a hospital in Chicago, his family said. The cause was not given.

Since Diplomacy’s inception, hundreds of thousands of copies have been sold, with games also being played on the Internet.

John F. Kennedy reportedly played it in the White House, and Henry Kissinger was a fan as well, according to newspaper accounts. Games magazine named it to its Hall of Fame alongside such classics as Monopoly, Scrabble, Clue, Yahtzee and Sorry!

Described as a thinking man’s version of the popular game Risk, Diplomacy is a seven-player game based on the balance of power in pre-World War I Europe. Players are free to bluff and backstab one another to attain world domination.

Quick games can take six hours; marathon sessions can stretch for days. And much like real diplomacy, there often isn’t a clear-cut winner because people just give up.

The son of an engineer and a schoolteacher, Calhamer was born in Hinsdale, Ill., on Dec. 7, 1931. He attended Harvard University on a scholarship and graduated in 1953. He went on to Harvard Law School, where he tested a prototype of what would become Diplomacy.

Calhamer dropped out of law school after a year and a half, then took the U.S. Foreign Service exam and spent three months on assignment in Africa. When he returned, he joined Sylvania’s Applied Research Laboratory in Waltham, Mass., where he did operations research, a scientific approach to military problem-solving, while continuing to perfect his game.

In 1959, Calhamer got Diplomacy onto the shelves of toy stores in New York, Chicago and Boston. The games sold out within six months. Game maker Avalon Hill then bought the rights and Diplomacy began to develop an international following.

Calhamer left Sylvania after six years, and while looking for work in New York as a computer programmer, took a job as a guard at the Statue of Liberty. It was during that time he met his future wife, Hilda They were married in 1967. She survives him, along with two daughters.

After marrying, Calhamer and his wife moved to the Chicago suburb of La Grange Park, where he began a 21-year career as a letter carrier.

“That proved to be pretty worthwhile,” Calhamer told Chicago magazine in 2009. “It doesn’t sound like a high-level job, but it was completely reliable, and it paid. I was pretty good at sorting mail. You have to be accurate.”

Last year, Chicago hosted the World Diplomacy Championship and the North American Grand Prix. Calhamer signed autographs, posed for photos and was given a standing ovation after briefly addressing his audience.

“I don’t think the game ever made Mr. Calhamer rich,” said Jim O’Kelley, founder of the Windy City Weasels, a club for Diplomacy players. “But it has enriched thousands of lives all over the world, including mine.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.