Bernice Gordon, longtime creator of crossword puzzles, dies at 101

- Share via

Bernice Gordon, who delighted, bedeviled and sometimes outraged aficionados of the crossword puzzle during a six-decade career unusual not only for its longevity but the artfulness of her brain-teasing constructions, died Thursday at her Philadelphia home. She was 101.

The cause was heart disease, said her son, Jim Lanard.

Gordon’s first crossword was published in the New York Times in 1952. Over the next decades she created hundreds of puzzles for major newspapers across the country, including the Los Angeles Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer. Her work also appeared in books published by Scribner, Dell and Simon & Schuster.

Crosswords “make my life,” she told the Associated Press after her 100th birthday last year. “I couldn’t live without them.”

Until two weeks before her death she was still producing a puzzle a day, usually between 3 and 6 a.m. She had shelves packed with dictionaries, almanacs and other tools of her trade, and constructed her puzzles on a computer, having given up paper and pencil a dozen years ago when she was nearly 90.

“That was her best creative time,” Lanard said Tuesday about his mother’s early-morning schedule. “Even when she was almost terminally ill, she was still up at her computer doing puzzles. She’d get excited about a new theme — colors, movies, you name it.”

A few years ago Gordon was inspired to create a puzzle around four clues: Obie, Odie, Opie and Okie. The answers, each 15 letters long, were THEATRICALAWARD, GARFIELDSFRIEND, CHILDINMAYBERRY and MANFROMMUSKOGEE.

Rich Norris, crossword editor of the Los Angeles Times, cites that puzzle as one of his favorites, in part because of the difficulty of molding an answer to a certain length.

Her crosswords were clever but not gimmicky and “almost always straightforward,” Norris said. “And they were elegant in their simplicity. She was able to find connections among words that were so obvious that you wondered why you hadn’t seen them before.”

Gordon’s career had begun out of boredom. Her first husband had died, making her life suddenly “very, very empty,” she recalled in the Penn Gazette a few years ago. “When I was by myself one night, I had a thought: I do a crossword puzzle every day. Suppose I try making one?”

She knocked one out with ease and submitted it to Margaret Farrar, the New York Times’ first crossword editor, but it was swiftly rejected. “I used two-letter words. I used words they had never heard of,” Gordon said of her virgin effort’s many flaws.

She made several more submissions before finally succeeding, in 1952. MAMIE EISENHOWER, who was about to become first lady, was one of the answers.

Thirteen years later, in 1965, Gordon shook up the crossword world when she decided to substitute symbols for letters. The rebus, an ancient form of expression, had not been used in a crossword before Gordon sent one to Farrar that replaced the letters a-n-d with an ampersand, as in S&CASTLE and CARMENMIR&A.

The puzzle elicited bags of mail from the faithful, many of whom praised its originality while others condemned it as devious.

But the rebus caught on.

“Today, rebus constructions are so common that editors warn constructors not to send them in because they already have large backlogs,” Ben Tausig wrote in his book “The Curious History of the Crossword.” Gordon, according to the author, turned the form into “a common element of the crossword landscape.”

Gordon’s life spanned nearly the entire history of the newspaper crossword puzzle. She was born in Philadelphia on Jan. 11, 1914, about three weeks after the first known crossword appeared in the New York Sunday World.

Gordon was the daughter of a Russian Jewish immigrant who sold pencils before becoming a successful dressmaker. She graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in fine arts in 1935. That year she married her first husband, Benjamin Lanard Sr. He died in 1947. Her second husband, Allen Gordon, died in 1967.

She also outlived a son, Benjamin Lanard Jr., who died a few days before she turned 100.

Besides her son Jim, of Scottsdale, Ariz., she is survived by a daughter, Amanda D’Amico, of Westchester, Pa.; four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

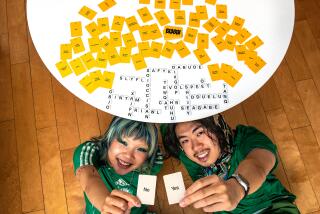

At 99, Gordon teamed up with a crossword builder more than 80 years her junior, California teenager David Steinberg. Their collaboration, conducted largely by email, hit a few generational bumps: He hadn’t a clue about her reference to a “handsome Harry,” for example, and she was mystified by his proposal to use the word “Uggs.” Will Shortz, crossword editor of the New York Times, which published the puzzle, described the end result as “phenomenal.”

“All her puzzles were built with meticulous care,” said Steinberg, now 18 and crossword editor for the Orange County Register. “She took the time to carefully select every word. She wanted them to be words in the dictionary, not necessarily pop culture references.”

Asked if he learned anything from her, he said, “More than anything I was inspired to keep constructing. No matter how old you get or what happens in life, keep doing what you love.”

In one of Gordon’s last early-morning brainstorms, she created a rhyming crossword featuring a six-letter sequence ending in UMBLE. That led her nimble mind to answers like HUMBLEHOME, RUMBLESEAT, TUMBLEWEED and DUMBLEDORE, said Norris, who published the puzzle in this newspaper Dec. 2.

Norris said it was the last Gordon puzzle published in a newspaper. Others will appear later this year in the “Mega Crossword Puzzle Book” series edited by John Samson.

Twitter: @ewooLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.