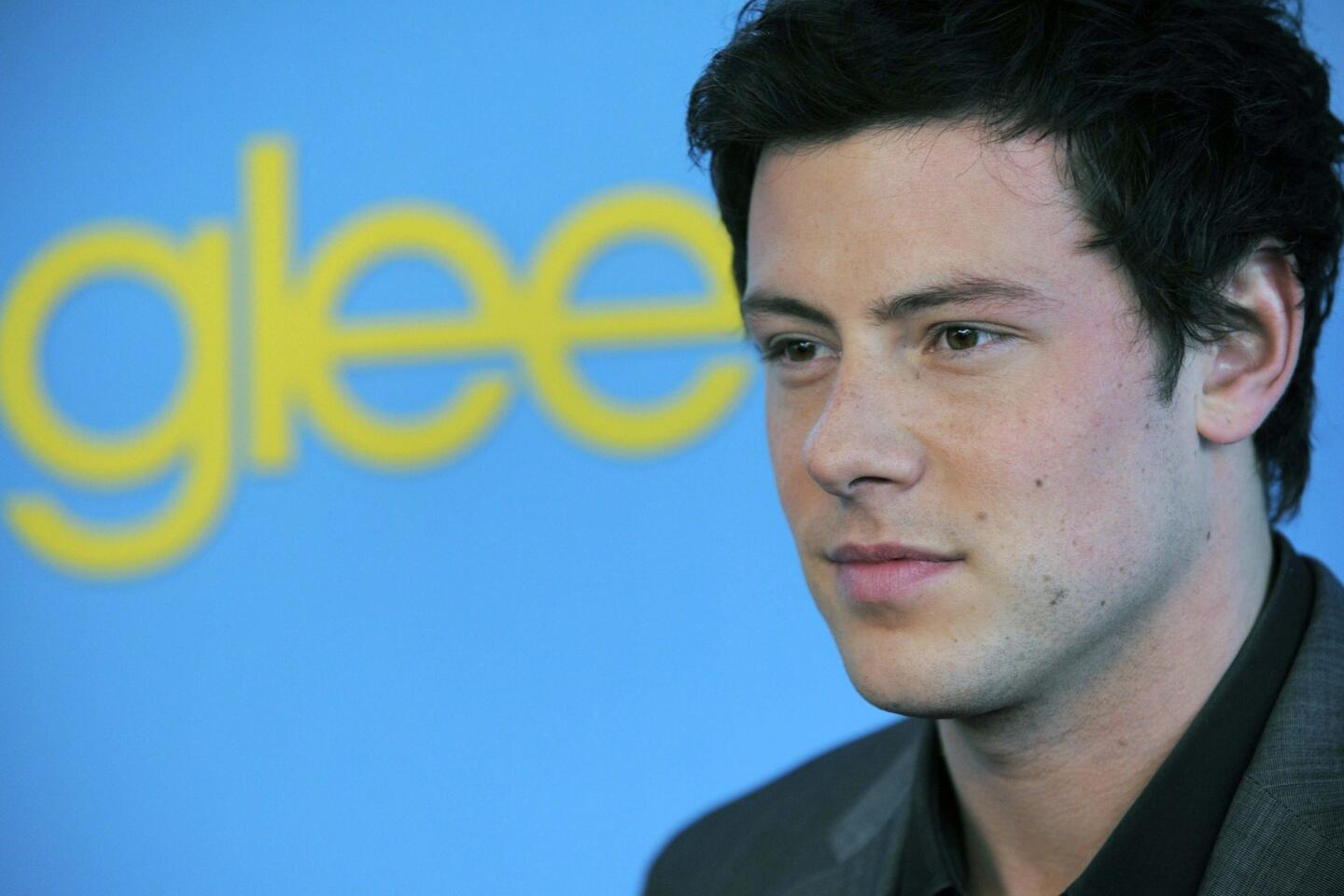

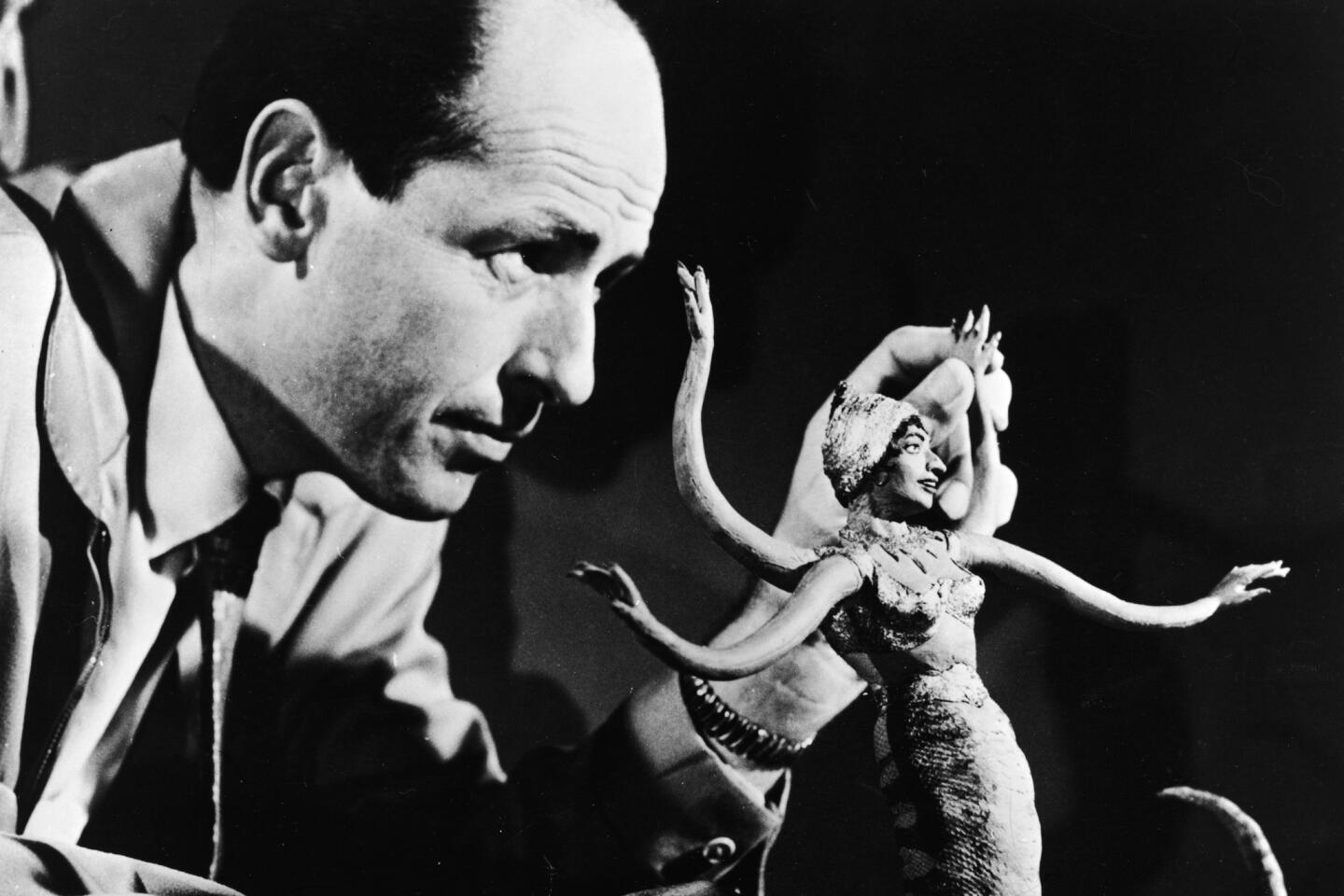

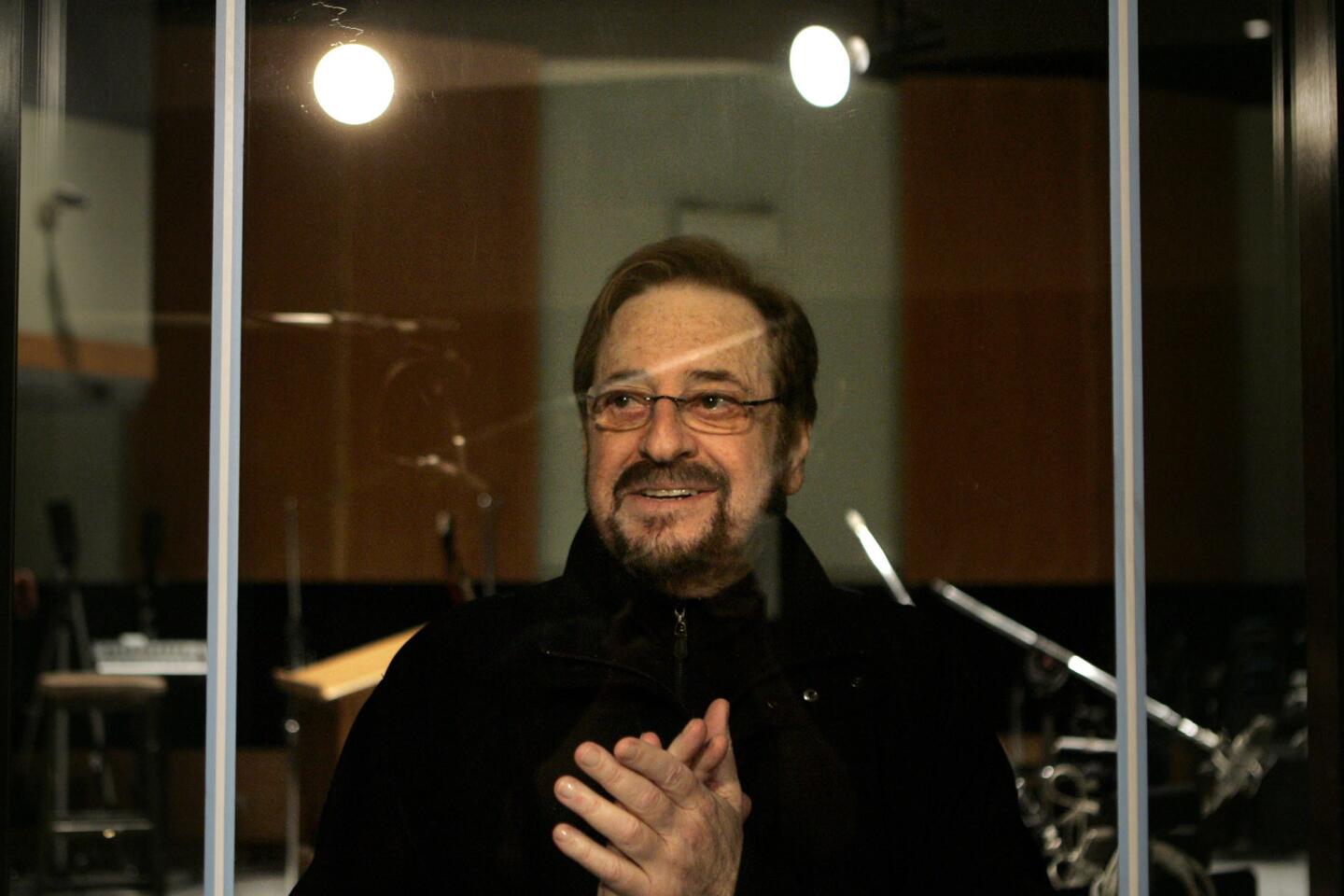

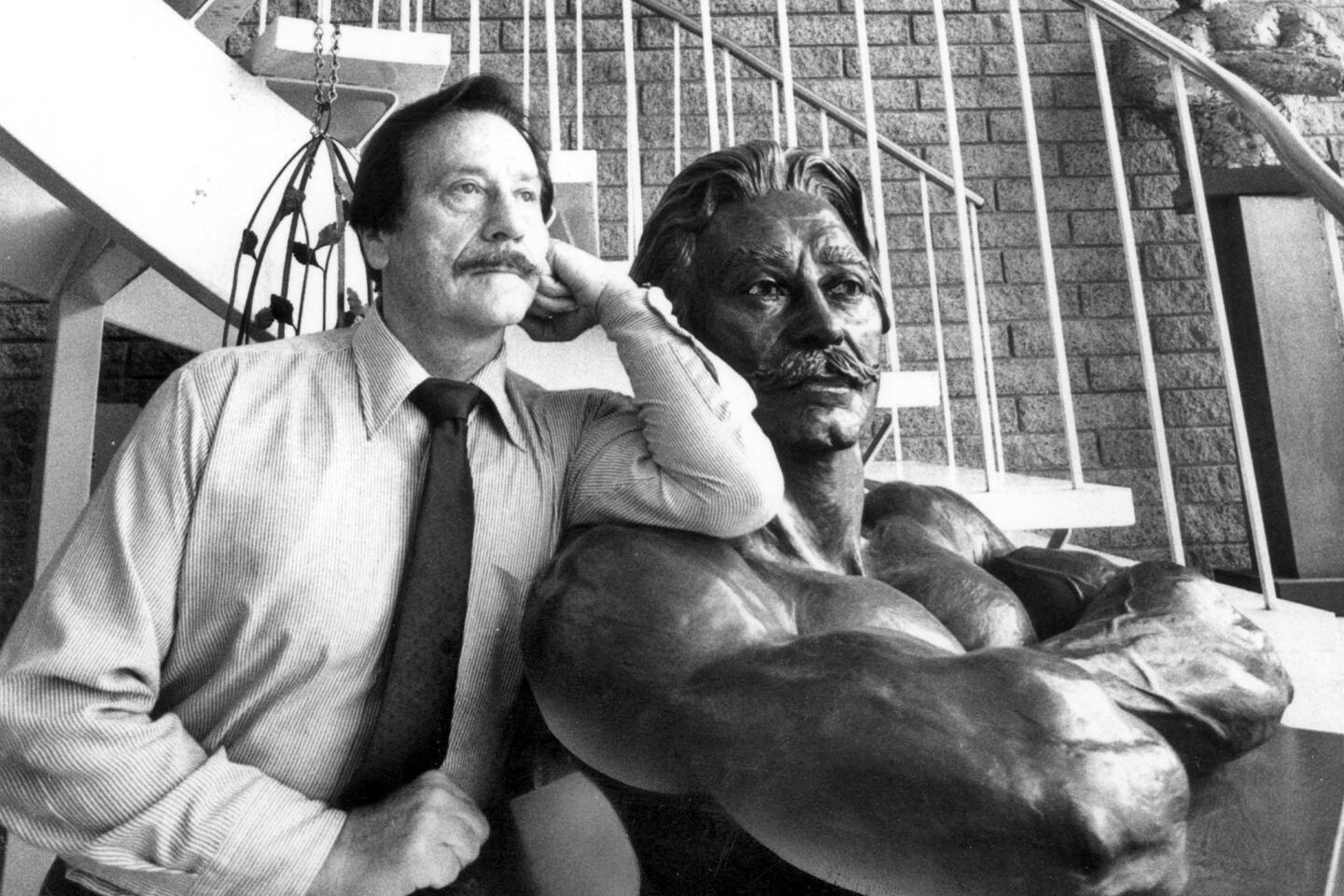

Bert Trautmann dies at 89; ex-Nazi and star England soccer goalie

- Share via

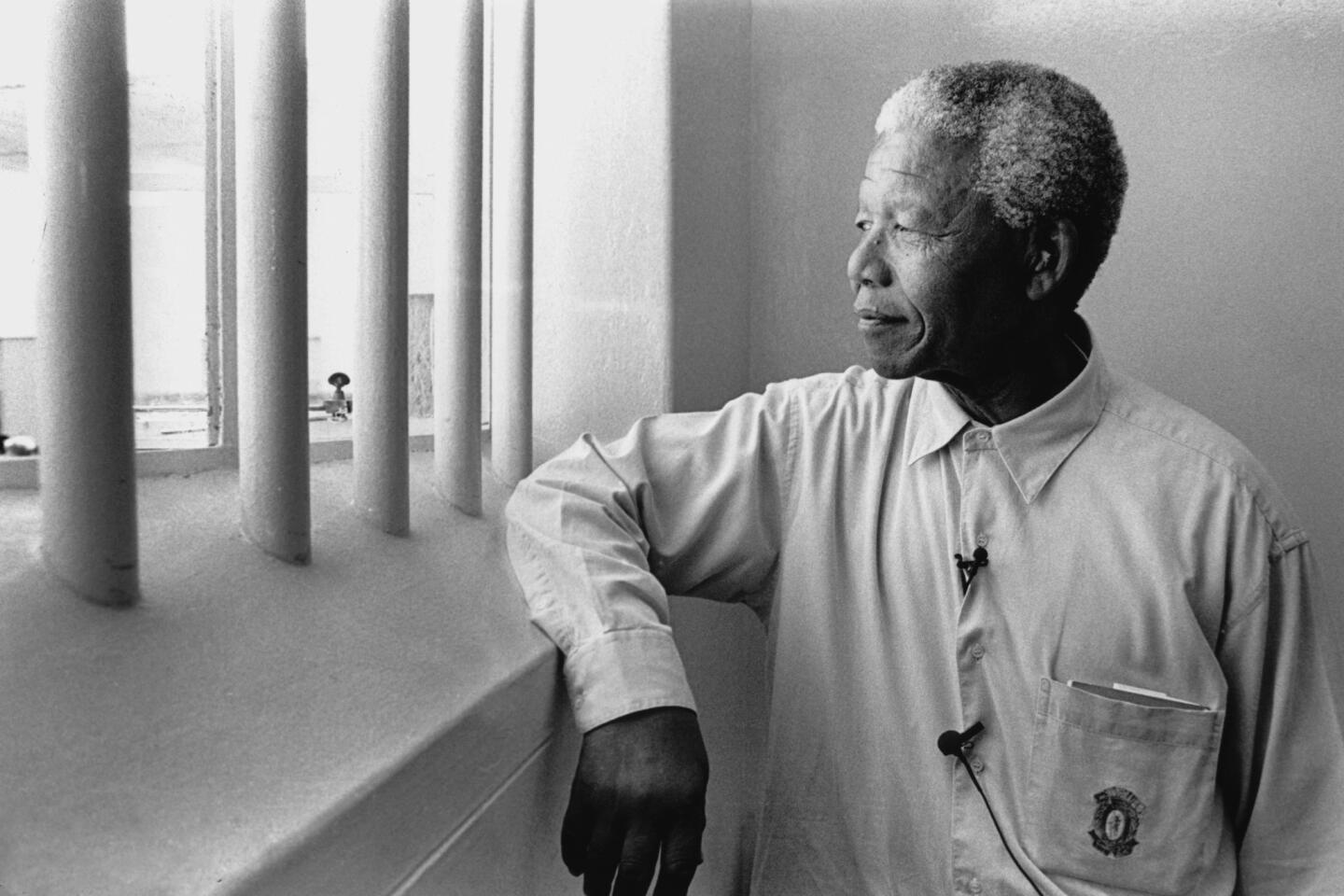

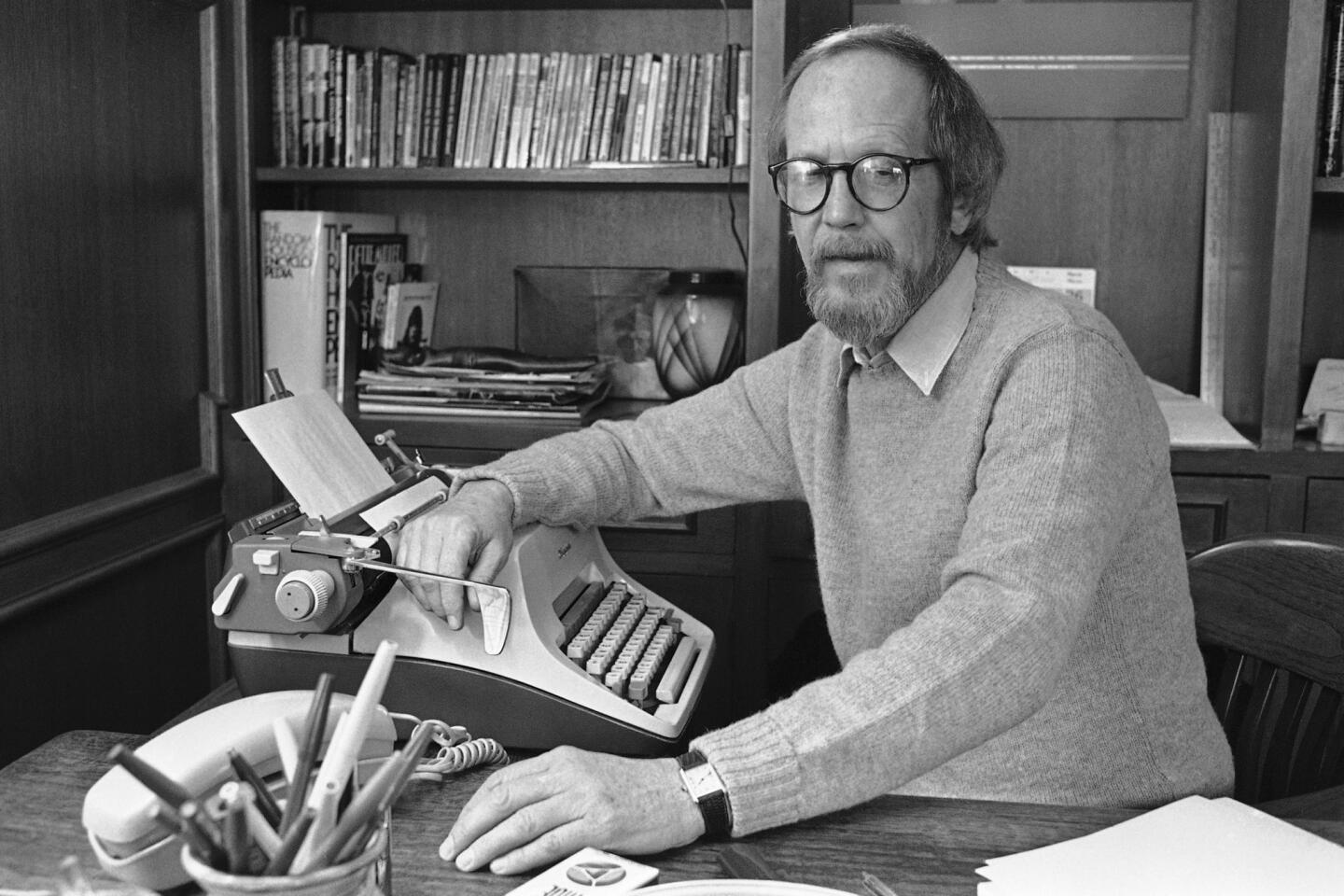

The first time former Nazi paratrooper Bert Trautmann faced his new teammates, the English soccer club Manchester City, in 1949, he was welcomed with these words: “There’s no war in here, Bert.”

The war-weary public was not so forgiving — until the native German and former prisoner of war quickly established himself as a stellar goalkeeper.

He helped Manchester City win the FA Cup in 1956, despite unwittingly playing the last 17 minutes of the final with a broken neck. Among his contemporaries, Trautmann was regarded as one of the greatest goalkeepers of all time.

Trautmann, who had two heart attacks this year, died Friday at his home in La Llosa, near Valencia, Spain, the German Football Federation announced. He was 89.

During World War II, an 18-year-old Trautmann joined the Luftwaffe and fought on the Eastern Front, earning five medals including an Iron Cross for gallantry. He was captured in Russia, and later in France, but escaped both times.

Fleeing from an American unit, he jumped over a fence and — in an oft-told story — landed at the feet of a British soldier, who greeted him by saying, “Hello, Fritz. Fancy a cup of tea?”

The British Army sent Trautmann to a prisoner of war camp in England, where he first started playing goalkeeper. He would later claim that his paratrooper training, which emphasized acrobatic dives, made it easier for him to fall on the soccer field without injury.

In 1945, Trautmann was one of only 90 members of his original 1,000-strong regiment to survive the war. He turned down the chance to be repatriated back to Germany and remained in England, where he married a local woman, worked on a farm and kept goal for a local soccer team.

His performance in a friendly match against Manchester City led the first-division club to sign him to a contract. After the decision was announced, 20,000 people protested and for years he received hate mail.

As he played in 245 of Manchester City’s next 250 games, Trautmann won over fans with his brilliant play in goal. The country’s soccer writers named him player of the year in 1956 — days before his legendary performance in that year’s FA Cup final.

Late in the final match, he sustained a serious injury while diving at the feet of Birmingham City’s Peter Murphy. Trautmann refused to leave the field and made a number of crucial saves to protect his team’s 3-1 win.

When he stepped forward to collect his FA Cup medal, his neck was noticeably crooked. Three days later, X-rays confirmed he had played the final minutes with a fractured neck.

Later that year his 5-year-old son, John, was hit and killed by a car. His first wife never recovered, he later said, and after 10 years of marriage the couple divorced. They had two other sons, and he also had a daughter from a previous relationship.

He continued playing soccer until he was 40, retiring in 1964. He moved into management with lower-division clubs in England and Germany and later helped develop soccer in Third World countries.

Trautmann admitted that it bothered him to be remembered primarily for playing with the neck injury and not for being the first German to play in an FA Cup final, in 1955.

“That was something absolutely magnificent,” he told the British media in 2011. “We lost 3-1 to Newcastle United.... But it was an amazing day and I just looked around the stadium and thought, ‘You lucky man.’ ”

He was born in 1923 in Bremen, Germany, into a working-class family. After enrolling in the Hitler Youth at age 10, he began to excel in sports.

“People ask, ‘Why did I join the Hitler Youth?’” he later said. “But they don’t understand. Growing up in Hitler’s Germany you had no mind of your own.”

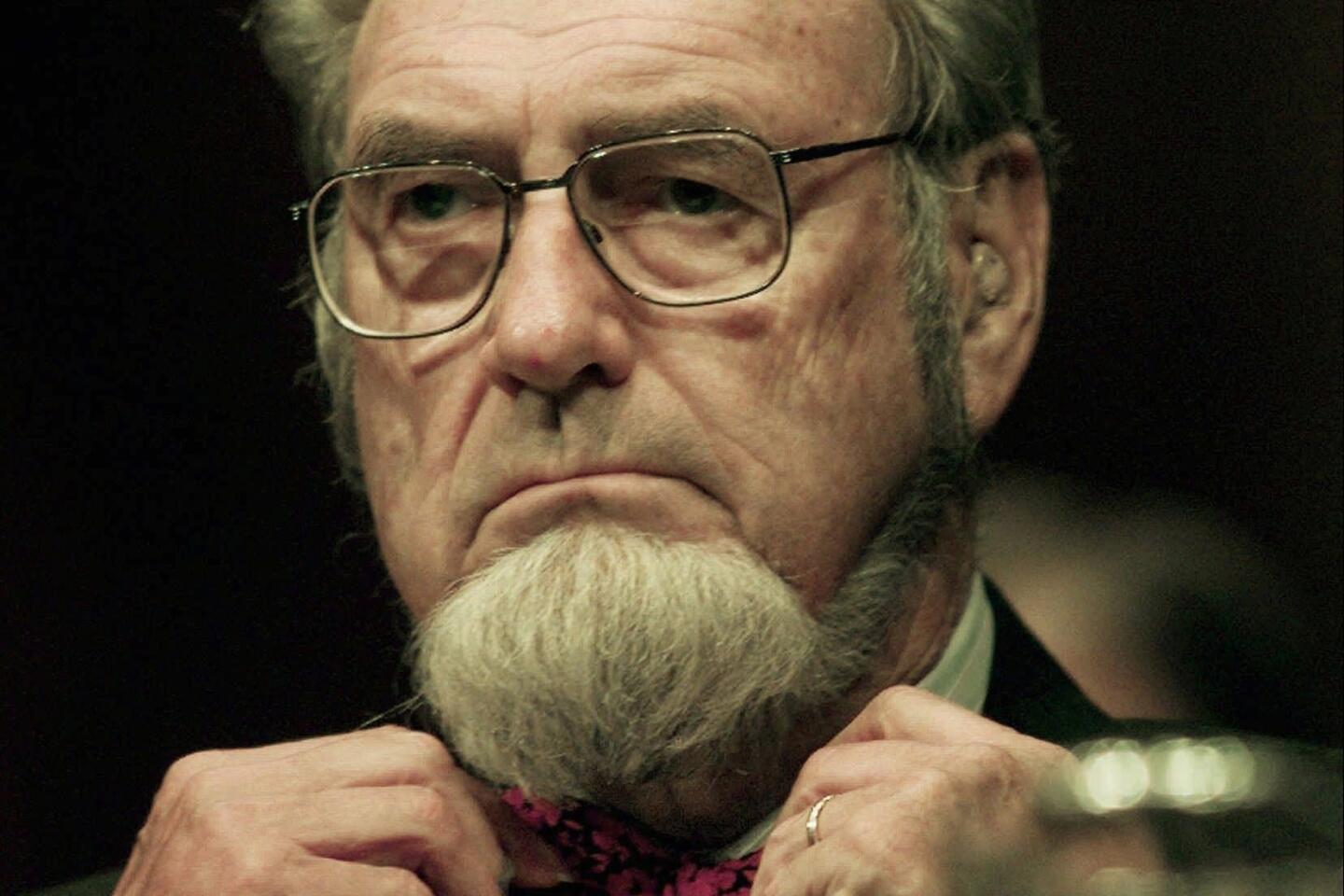

Trautmann received one of England’s highest honors in 2004 when he was appointed an honorary Office of the Order of the British Empire for promoting Anglo-Germany relations through soccer.

He retired to Spain, where he lived with his third wife.

“I feel British in my heart now,” he said in a 2010 interview in the British press. “When people ask me about life, I say my education began when I got to England. I learnt about humanity, tolerance and forgiveness.”

Times staff writers Valerie J. Nelson and Kevin Baxter contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.