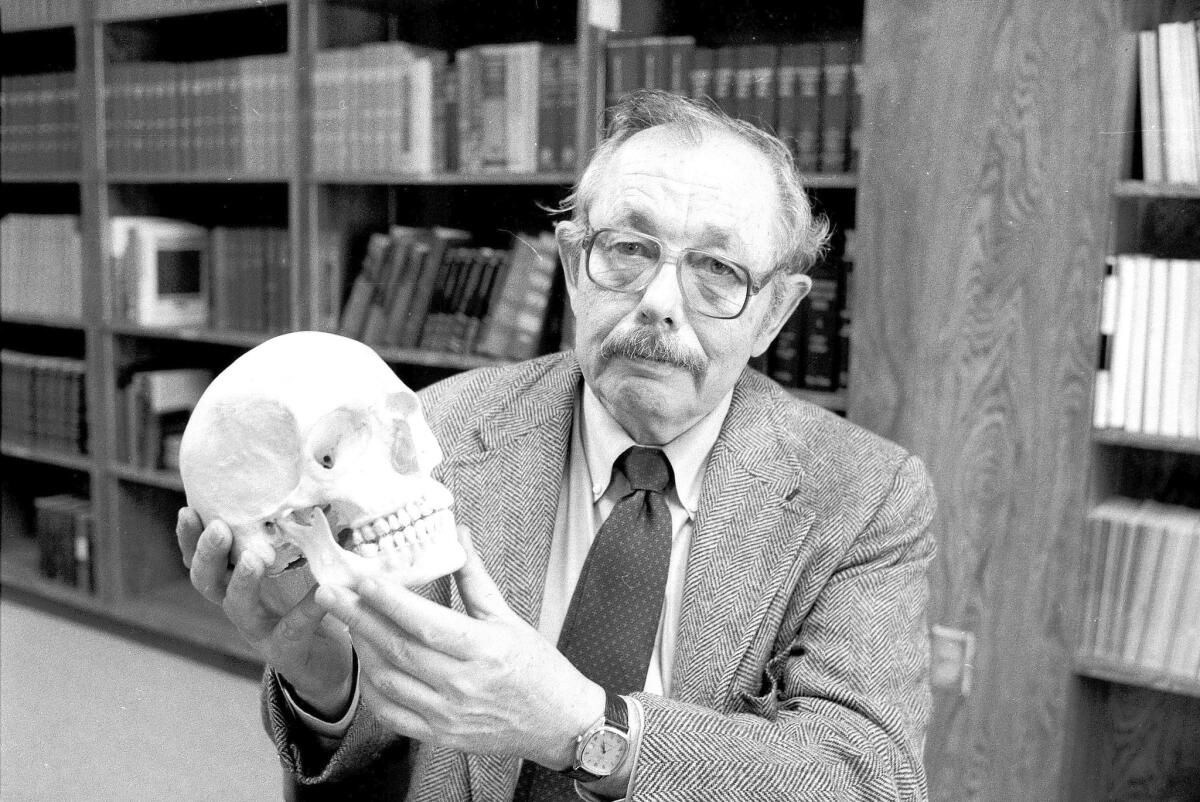

Clyde Snow dies at 86; forensic anthropologist read old bones’ secrets

- Share via

When Clyde Snow testified at the 2006 genocide trial of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the defendant confronted him with a question Snow futilely yearned to answer.

As one of the world’s foremost forensic anthropologists, the wisecracking, chain-smoking Oklahoman had been on the witness stand many times before. But seldom had he been given the kind of golden opportunity he was handed in court by the deposed dictator, who contended that the bones in a mass grave examined by Snow could have been those of Hittites from thousands of years before.

“I knew the Hittites were an advanced civilization,” Snow wanted to say, “but I didn’t know they were so advanced that they had digital wristwatches. And I would have found it even more puzzling that all of them stopped short of or a few days after Aug. 28, 1988 — the date of the massacre.”

A judge dismissed Hussein’s question, but over the decades, Snow had many other chances to unveil the secrets told by old bones. When human rights groups came to him for scientific proof of hidden atrocities, Snow helped out, sometimes on his own dime. Over decades, he hauled his digging tools, calipers and encyclopedic knowledge of anatomy into remote regions of the world’s bloodiest countries: Chile, Guatemala, El Salvador, Iraq, Congo, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, the former Yugoslavia.

Snow was on a team that identified skeletal remains exhumed in Brazil as those of infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. He led an effort to find and identify Argentina’s desaparecidos — the thousands of “disappeared” citizens who were murdered and tossed into unmarked graves by a brutal regime. In El Salvador, he studied the remains of 136 buried children who had been sprayed with machine-gun fire.

Snow, who also was consulted for scientific evidence in high-profile U.S. crimes including the assassination of President Kennedy, died May 16 at a hospital in Norman, Okla. He was 86.

He had lung cancer and emphysema, said his wife, Jerry Whistler Snow.

Clyde Snow told rambling stories in his native West Texas drawl over Bombay martinis straight up with two olives. He carried a gold badge from the Illinois Coroners Assn. that he described as “vulgar as hell” but effective in cowing local officials. With his typically dry wit, he liked to say he spent more time in Latin American cemeteries than many dead people.

But his purpose, as he stated it at a 1984 meeting of the American Assn. for the Advancement of Science, was irrefutably serious: To keep governments from killing for “a careless word, a fleeting thought or even a poem.”

Months later, Snow was in Buenos Aires. A repressive military government had been replaced in a 1983 election, and Argentina’s new leaders wanted to cast light on the disappearance of leftists — 10,000 to 30,000, by varying estimates. Some had been buried in potters’ fields, in graves marked N.N. for “no nombre.”

With a “raggedy-taggedy team” of students, Snow uncovered some 500 skeletons, many with bullet-shattered skulls and broken fingers. In court, he described how the bones of a young woman named Liliana Pereyra indicated she was tortured while pregnant.

Snow’s testimony helped convict five former military leaders.

Born Jan. 7, 1928, in Fort Worth, Texas, Clyde Collins Snow was the son of a doctor in the tiny West Texas town of Ralls.

An unambitious student, he was expelled from high school over a prank involving the planned detonation of firecrackers during a visit by a state education official.

After a few false starts, he finally received a bachelor’s degree from Eastern New Mexico University, a master’s degree from Texas Tech and, in 1967, a doctorate in anthropology from the University of Arizona.

After serving in the Air Force, Snow worked at a Federal Aviation Administration lab in Oklahoma City.

He directed a study of three air disasters that conveyed a brutal truth: In a panicked scramble for the exits, mature men survived and children did not.

In a 1979 American Airlines crash outside Chicago, all 271 people aboard and two on the ground died. Snow helped identify their remains.

Over the years, Snow refined old techniques and developed new ones. In a day before sophisticated DNA analysis, he found the hints given in bones about childhood diseases, ethnicity, height, even occupation. He solved one case by studying the spider webs in a victim’s skull.

When the three-decade-old remains of a little girl were discovered in Chicago, he could tell she was shaken to death by someone with long fingernails. The girl’s mother confessed.

Snow identified many of the boys killed in the 1970s by John Wayne Gacy, the Chicago man who stashed bodies beneath his house.

Snow helped confirm that X-rays taken after the Kennedy assassination were in fact of the slain president. But his findings weren’t always positive: In a Bolivian cemetery, a body thought to be the Sundance Kid turned out to be a German miner named Gustav Zimmer.

Snow had projects involving many historic figures, including Tutankhamen, the Egyptian pharaoh, and the doomed soldiers of Gen. George Armstrong Custer.

Although he had confronted human mortality thousands of times, Snow would get upset when his wife killed mice at their home.

“He’d say: ‘There’s enough death and destruction in my work,’” she recalled. “I’d sneak around and set traps when he was out of town.”

In his hospital room days before he died, Snow reviewed findings he had made in 1972 on skeletons unearthed at an Arkansas prison farm.

A professor at the University of Oklahoma, Snow mentored students around the world.

“He told them to be scientists first but not to forget their humanity,” said Eric Stover, a law professor at UC Berkeley who worked with Snow in Argentina and elsewhere. “‘Cry at night,’ he’d say.”

In addition to Jerry, his wife since 1970, Snow’s survivors include daughters Jennifer Boles, Tracey Murphy, Cynthia Wood and Melinda McCarthy; son Kevin Snow; eight grandchildren; and eight great-grandchildren.

Three previous marriages ended in divorce.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.