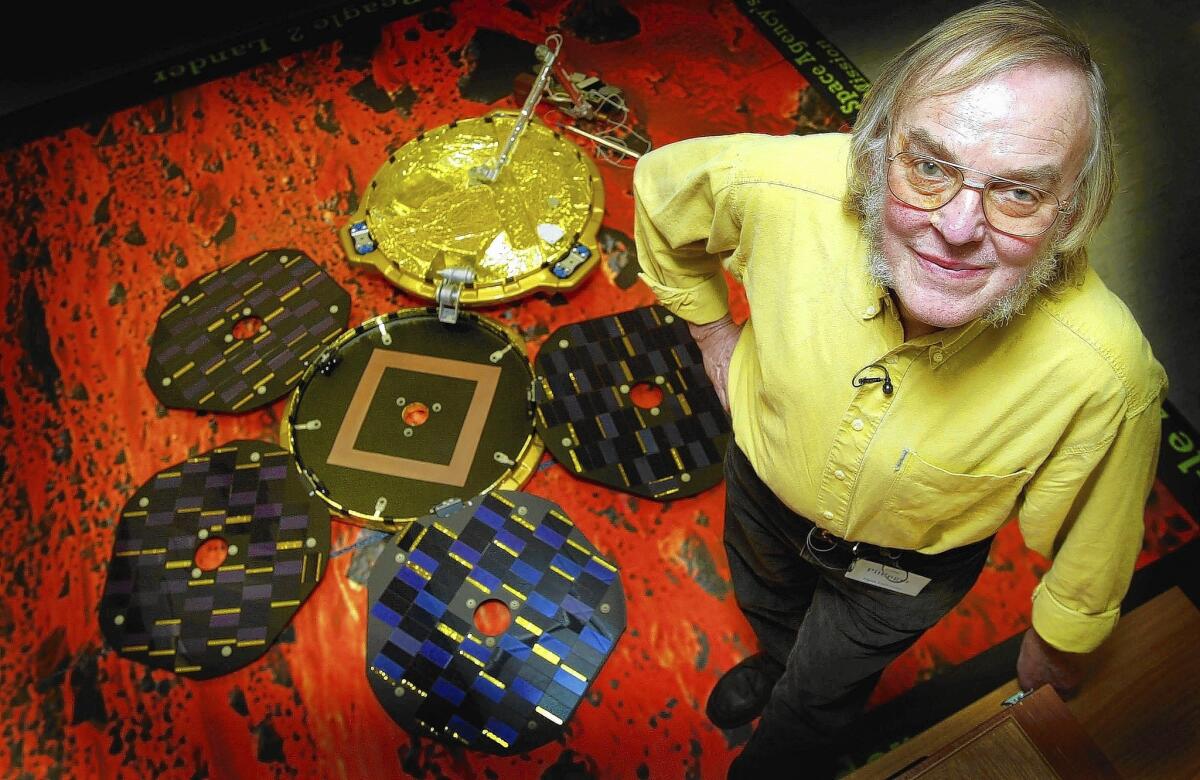

Colin Pillinger, colorful scientist of failed Mars probe, dies at 70

- Share via

Colin Pillinger, a colorful British space scientist who sported thick mutton-chop whiskers and became a symbol of national pluck in masterminding a failed search for life on Mars, died Thursday in a Cambridge hospital. He was 70.

Pillinger collapsed in his garden after a brain hemorrhage, his family said in a statement.

The Beagle 2, a 155-pound landing craft that Pillinger developed despite bureaucratic resistance, was lost as it approached the surface of Mars on Christmas Day 2003. Nobody knows whether it burned in the Martian atmosphere, shattered on impact or failed to perform once it landed.

A geochemist with a flair for public relations, Pillinger was philosophical about its demise.

“Everyone knew how hard it would be to land on Mars,” he told reporters, “however easy it looks in the pub after the third pint.”

Outside the pub, there were plenty of skeptics. Beagle 2 was built for an estimated $85 million — a small sum in the world of space exploration. It was designed to analyze Martian soils for signs of life past or present — a task already tried by NASA’s Viking landers in the 1970s.

“They came up empty,” said Matthew Golombek, a senior research scientist at Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a veteran of Mars projects. “But Pillinger was convinced he had a different way to do it.”

“He was a true explorer,” Golombek said, adding that a Martian crater had been named Beagle after Pillinger’s effort. The Beagle 2 was named after the ship Charles Darwin sailed on his 19th century voyages of exploration.

Pillinger spent seven years on the project, raising private funds and persuading British officials to contribute public money as well. Along the way, he triggered widespread public support with help from the British rock group Blur, creators of an album called “Modern Life Is Rubbish.”

Blur also composed a distinctive, nine-note signal that the Beagle was supposed to send to a U.S. Mars Odyssey spacecraft after it landed. The signal was never received. A scan of Mars by a giant radio telescope at Jodrell Bank in England was also futile.

Waiting for word along with Pillinger, the United Kingdom had become “a nation of Beagle-watchers,” the Scotsman newspaper said in 2003. “We are rooting for a little, technology-packed entity about the size of a garden barbecue, which has traveled an unfeasible distance against innumerable odds.… He has made us believe in Beagle not as a machine but as a living thing.”

For his part, Pillinger poetically compared the Beagle to a love letter.

“You know they’ve got it,” he said, “and you’re waiting for a response.”

Born in Bristol, England, on May 9, 1943, Colin Trevor Pillinger was hooked on the notion of space travel by science fiction radio dramas he heard as a boy.

As a chemistry student, he once recalled, he was “a disaster.”

“Every time I mixed two solutions, they ended up on the ceiling,” he said. “It was only when I discovered you could do chemistry with instruments that I found my vocation.”

Earning his doctorate at the University of Wales, Pillinger became an expert in the use of the mass spectrometer and other equipment employed to analyze the composition of materials. He studied moon rocks brought back by U.S. astronauts and scanned meteorites for evidence of organic materials.

When the European Space Agency was planning an unmanned Mars expedition, Pillinger talked his way into committee meetings and pumped up the notion of the Beagle 2, an apparatus that would be dropped from a satellite, deploy a parachute, scoop up Martian soil and transmit whatever it discovered.

He attracted high-level supporters. Queen Elizabeth II was a booster and so was the manufacturer of Ferrari sports cars, which included a tiny canister of Ferrari red paint on the trip to Mars. Avant-garde artist Damien Hirst contributed a dot painting that Beagle’s cameras were to use for calibration. A Hong Kong dentist designed its drill.

Although he was comfortable in the limelight, Pillinger was once described as “perpetually leaning on the gate of science with a straw in his mouth.” He and his family had a small dairy farm and he didn’t allow computers in his home.

“There is nothing like sticking your hand up the backside of a cow to help deliver a calf to take your mind off the troubles of the modern world,” he told The Observer, a British newspaper, in 2003.

Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2005, Pillinger wheeled around on a motorized scooter. He taught for many years at The Open University, a British distance-learning school, and was still active in space research.

But he was best remembered for his Mars probe.

“Had Beagle 2 survived the landing, Pillinger would have been a national hero,” The Guardian newspaper said in 2010. “Had he found chemical evidence of Martian life … he would have become an international superstar.

“He remains a hero anyway,” the paper said. “He had a go.”

Pillinger’s survivors include his wife, Judith, daughter Shusanah, and son Nicholas.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.