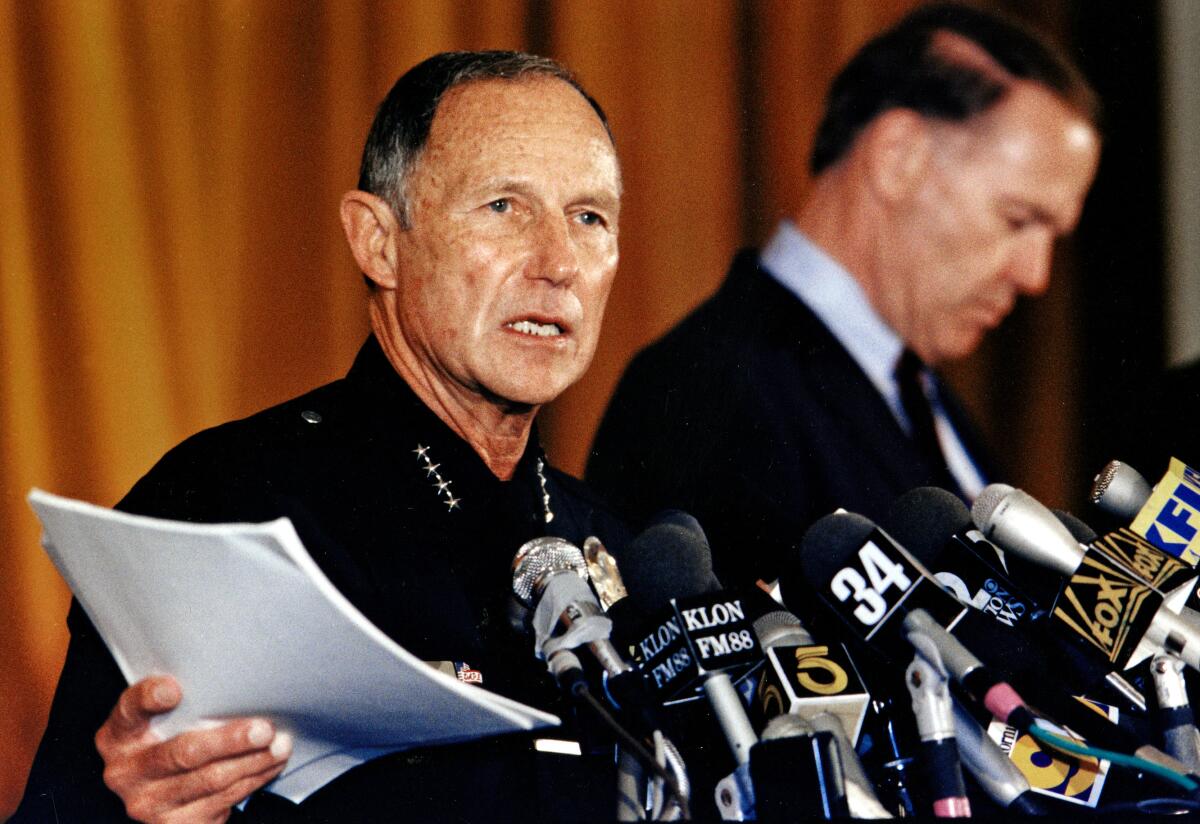

Daryl F. Gates dies at 83; innovative but controversial chief of the LAPD

- Share via

Daryl F. Gates, the rookie cop who rose from driver for a legendary chief to become chief himself, leading the Los Angeles Police Department during a turbulent 14-year period that found him struggling to keep pace with a city undergoing dramatic racial and ethnic changes, died Friday. He was 83.

Gates died at his Dana Point home after a short battle with cancer, the LAPD announced.

The controversial chief, whose tenure ran from 1978 to 1992, spent his entire four-decade career at the LAPD, where he won national attention for innovative approaches to crime fighting and prevention: He instituted military-style SWAT teams to handle crises and the gentler DARE classroom program to prevent drug abuse. These initiatives, emulated by police departments across the United States, and other advances, such as a communications system that reduced police response times, bolstered his reputation as an exemplar of modern law enforcement. President George H.W. Bush called him an “all-American hero.”

A proud emblem of progress to some, he was a disturbing symbol of stagnation to others. When the city went up in flames over the acquittal of four white officers accused of beating black motorist Rodney King, he was castigated as a leader out of touch with the changing realities of the city, yet to the end he remained righteous about his authority to police it.

Faced with a proliferation of illegal drugs and street violence, he hammered gangs with police sweeps and broke into crack dens with a steel battering ram on an armored vehicle. He made no apologies for declaring that casual drug users should be shot.

By turns charming and brash, articulate and tactless, he generated controversy with gaffes about Latinos, blacks and Jews, most famously with a remark about blacks faring poorly under police chokeholds because their physiology was different from that of “normal” people. Fiercely loyal to his rank and file, he clashed frequently with elected officials, particularly when they slashed his budget or meddled in department discipline. He vowed he would never be bullied by “crummy politicians.”

Parker’s protege

Gates “fought vigorously to make sure the chief’s duties were not encroached upon. That comes from understanding the struggles Bill Parker went through moving the department out of corruption,” said City Councilman and former Police Chief Bernard C. Parks. He was referring to William H. Parker, the tough, reform-minded chief in the 1950s and ‘60s, who became Gates’ mentor.

Parks said it was important to remember that the vilification of Gates after the King beating was not universal and that his accomplishments as chief mattered to large segments of the city long after he left the department.

“If you go to areas of the Valley, police organizations, officers’ funerals . . . he gets the loudest ovation,” Parks noted recently. “I’ve never seen a situation where . . . 18 years after retirement, officers who never worked with him cheer him as chief of police.”

Yet others just as vehemently argue that Gates’ strengths were outweighed by his weaknesses, particularly his failure to evolve with a region transformed by demographic explosions. Between 1980 and 1990, the population of Latinos in Los Angeles County grew by 62.2%, and Asians and Pacific Islanders by 107.5%. Meanwhile, the white population was contracting, dropping by 8.5%.

Although the African American population grew far more slowly during that decade, its political leadership had matured. Los Angeles had black representatives in Congress, the state Legislature and the City Council. In 1973, Tom Bradley, the former LAPD lieutenant and councilman, united a diverse coalition of constituencies to become Los Angeles’ first African American mayor. Gates had a fractious relationship with Bradley throughout his tenure as chief.

“This L.A. was a changing city. . . . He never made the adjustment to the new L.A.,” Ramona Ripston, the longtime head of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said recently of Gates.

In 1991, the videotaped beating of King was replayed around the world, shattering the carefully nurtured myth that the LAPD of “Dragnet” fame -- professional, honest and humane -- never stooped to such behavior. Gates was slow to criticize his officers’ handling of the incident and was missing from his command post when the officers’ acquittal provoked the worst urban violence in decades, causing at least 53 deaths and more than $1 billion in property damage. With characteristic defiance, he rejected the inevitable calls for his resignation. It was not the first time that critics had demanded his ouster, but it would be the last.

Glendale childhood

Gates’ combative style can be traced to a hardscrabble childhood in Glendale, where he was born Aug. 30, 1926. When the Depression hit a few years later, his father, a plumber, took to drinking and frequently disappeared from home. His mother found a job in a dress factory, leaving Gates and his two brothers, Lowell and Stephen, to fend for themselves.

Police often barged into their ramshackle home looking for the senior Gates, whose debts and alcoholic behavior got him into trouble. The harsh treatment of his father gave Gates a dim view of law enforcement as “just a plague on society,” he wrote in his 1992 memoir, “Chief: My Life in the LAPD.” He had so little respect for the police that when he was 16 he punched an officer for writing him a parking ticket and was hauled to jail. The charges were dropped when he reluctantly apologized.

In 1943, after graduating from Franklin High School in Highland Park, Gates joined the Navy and served two years as “a plain old seaman” on a destroyer in the Pacific. After his discharge, he enrolled at Pasadena City College and married a classmate, Wanda Hawkins. He was taking pre-law courses at USC when he learned that she was pregnant. Unsure how he was going to support a family, he did not greet the news happily.

When a friend suggested that he join the Los Angeles Police Department, he said there was no way he would ever become “a dumb cop.” He changed his mind when he realized that earning the then-considerable sum of $290 a month to train at the Police Academy while continuing his USC studies was too good to refuse. On Sept. 16, 1949, he joined the force.

He started out in the traffic division, working as an accident investigator until he was transferred to patrol. He completed his rookie year still intending to be a lawyer when he was tapped to serve as driver and bodyguard for Parker, newly installed as chief. Over the next 16 years, Parker shaped the department into one of the most highly regarded in the country.

Parker talked a lot as Gates drove around the city, and Gates listened, soon earning a reputation as the chief’s fair-haired boy. “What I received during my 15 months with him turned out to be more than a primer on policing,” Gates wrote. “It became a tutorial on how to be chief.”

When he returned to the field, Gates worked juvenile patrol, then vice, before winning promotion to sergeant in 1955. He studied hard for every promotion exam and earned top scores that enabled him to make lieutenant in 1959 and captain in 1963.

In the spring of 1965 he rose to inspector, a position now called commander. He was overseeing patrol officers in the Watts area when long-festering racial tensions surfaced that summer.

The were sparked by the drunk-driving arrest of a black man named Marquette Frye. When his mother attempted to intervene, a crowd gathered. After several unsuccessful attempts by officers to disperse the crowd, rocks and bottles began to fly and the officers pulled out. Angry mobs began to spring up throughout the area. “We had no idea how to deal with this,” Gates later said. Six days of violence left 34 people dead, more than 1,000 injured and 600 buildings damaged or destroyed.

Parker died in 1966. Under Parker’s successor, Tom Reddin, Gates was promoted to deputy chief in 1968. The following year, under Chief Ed Davis, Gates became assistant chief.

In 1970, five years after his first marriage ended, he married Sima Lalich, a United Air Lines flight attendant. She filed for divorce in 1994.

Amid the turmoil of the late 1960s, Gates had, at Reddin’s request, begun to develop a special unit to respond to crises. Gates recruited 60 of the department’s top marksmen and called the team SWAT. He originally meant the acronym to stand for Special Weapons Attack Team, but then-Deputy Chief Davis thought “attack” was impolitic, so Gates changed the name to Special Weapons and Tactics.

SWAT’s first test came in a shootout at a Black Panther stronghold on Central Avenue on Dec. 8, 1969. “We were roundly criticized for our brutal activity,” Gates noted later, but the SWAT team weathered the controversy and went on to prove its value by resolving other crises without bloodshed.

When Davis resigned to enter politics, Gates applied for the job, coming in second behind an outside candidate on the Civil Service exam. When credited for his years of experience, the 29-year LAPD veteran moved into first place and was approved by the Police Commission despite concerns that he would flout civilian oversight. He was sworn in as the LAPD’s 49th chief on March 28, 1978.

His troubles began almost immediately.

About a month after his swearing-in, Gates addressed a Latino civil rights group, where he shared an observation that black officers sought promotions more aggressively than Latinos. Describing a conversation with a Mexican American lieutenant who had failed the captain’s written exam, Gates said he told the officer that the reason he failed was that he hadn’t studied hard enough. “You’re lazy,” the chief scolded.

The next day’s headlines blared that Gates had disparaged Latinos. The controversy raged for weeks.

A few months later, a black woman named Eulia Love reportedly struck a gas company employee with a shovel in a dispute over an overdue bill for $69. When two patrol officers escorted another gas company worker to her house in South Los Angeles, she threw a knife at them. The officers shot her eight times, killing her.

“Any way you viewed it, it was a bad shooting,” Gates said years later. Nonetheless, he decided at the time that the shooting was within department policy.

Then came a rash of LAPD scandals in which officers were accused of cavorting sexually with teenage Explorer Scouts, getting drunk in police station parking lots, consorting with prostitutes and stopping motorists to rob them of their wallets. Two members of a special LAPD burglary unit pleaded guilty to stealing electronic equipment from a shop in Hollywood.

Gates got much of the blame from the media, citizens and politicians, including Bradley. Several high-ranking officers even suggested privately that Gates should step down.

City Hall trimmed his budget requests and required him to hire more women, minorities and civilians. He struggled to police the nation’s second-largest city with a force that was too small for its size, compared to other major cities: At the end of his tenure, Gates said, Los Angeles had two officers per thousand residents, in contrast with New York’s and Chicago’s four per thousand.

Critics considered him incapable of adapting to changing attitudes. He was forced to disband his special unit, the Public Disorder Intelligence Division, which conducted surveillance on “subversives,”political figures and LAPD bashers such as the American Civil Liberties Union.

“All these people don’t know what the hell they’re doing, telling me how to run my organization,” Gates bristled.

That was strong language from the chief, a usually courteous and even courtly man who seldom raised his voice in anger. But for all of Gates’ seeming self-control, the intemperate remarks kept spewing forth.

After officers were criticized for using a carotid chokehold that caused injury and sometimes death, Gates commented: “We may be finding in some blacks that when it is applied, the veins or arteries do not open up as fast as on normal people.”

When criticized for that remark, Gates said he had meant people of all races with healthy arteries. “One stupid word,” he lamented.

Despite his reputation, it was Gates who in 1979, with the approval of the City Council, supported and adopted Special Order 40, which forbade officers from making inquiries about the immigration status of people they encounter or detain.

The measure has become increasingly controversial over the years, as the debate over illegal immigration has heated up -- with Arizona legislators recently passing a law directing police to determine whether people are in the country legally.

One of Gates’ proudest achievements came in 1983, when he met with officials at the Los Angeles Unified School District. Together they created the Drug Abuse Resistance Education program, or DARE, which sent uniformed officers to elementary classrooms to talk about the perils of drug use.

The 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics also were a huge success. Police security was tight but not oppressive, and the Games went off without incident.

Gates remained popular in many circles -- with conservatives and even to the end of his life with rank-and-file officers. But his tendency to shoot from the lip continued to hurt him. In 1990, for instance, Gates, whose own son had problems with drugs, said in testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee that “casual drug users ought to be taken out and shot.”

But that was nothing compared with the surge of outrage that followed the brutal 1991 arrest of King.

Videotaped beating

Officers stopped King after a high-speed chase that ended in Lake View Terrace. A graphic videotape shot by a resident showed King face-down on a dark street being kicked and savagely beaten by several LAPD officers as other officers stood by and watched.

King, who had been driving under the influence and evading pursuing officers, suffered multiple injuries, including a broken cheekbone, fractures at the base of his skull and a broken leg. Despite the officers’ contentions that King had threatened their lives, he was never charged.

With a national furor building, nothing Gates said publicly about the beating satisfied critics. Hesitant at first to criticize the officers involved, he called the incident “an aberration.” He apologized to King in a backhanded way, calling attention to King’s status as a parolee with a long arrest record.

Conservative columnist George F. Will, then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson and Gates’ longtime nemesis, Bradley, demanded that the chief step down, but Gates refused and the battle began.

The Police Commission placed Gates on paid leave, but a judge ordered his reinstatement a few days later.

On July 10, 1991, an investigative panel headed by Warren Christopher, who later became U.S. secretary of State, issued a scathing report on the LAPD, saying it was apparent that “too many patrol officers view citizens with resentment and hostility; too many treat the public with rudeness and disrespect. . . .

“The problem of excessive force in the LAPD is fundamentally a problem of supervision, management and leadership,” the Christopher Commission said.

The commission called for a “fundamental change” in LAPD values. And it called for a new chief. So did several newspapers, including The Times.

The next 11 months turned into an acrimonious contest of wills.

Gates announced he was leaving, then he said he wasn’t, then he said he was just bluffing when he said he was staying. When Police Commissioner Stanley Sheinbaum or Bradley demanded he resign, he retorted that he would leave if they went with him.

He was not on speaking terms with Bradley on the afternoon of April 29, 1992, when the four LAPD officers indicted in the King beating were acquitted by a Ventura County jury meeting in Simi Valley. Within hours, mobs began setting fires, looting stores and beating motorists in the worst outbreak of violence in Los Angeles history.

The rioting erupted at Florence and Normandie avenues while Gates was attending a Brentwood function to raise funds in opposition to a police-reform ballot measure. Several hours passed before he returned to take charge, and by then his officers were in full retreat. By the time order was restored two days later, with an assist from the National Guard, at least 53 people had died.

Gates blamed two subordinates, but a panel led by former FBI and CIA director William H. Webster placed the responsibility with Gates, saying the chief had “failed to provide a real plan and meaningful training to control the disorder.”

On June 28, 1992, Gates finally stepped down, ending weeks of suspense. His departure was engineered by City Council President John Ferraro, although Gates insisted the decision was his alone.

In the months that followed, King, who had been on parole for armed robbery and whose life continued to be plagued by run-ins with police for drug violations and other offenses, was awarded $3.8 million from the city as compensation.

The four officers acquitted in Simi Valley were retried in federal court on charges of violating King’s civil rights. Two were convicted and served prison terms.

In his post-LAPD years, Gates had a 15-month stint as a talk-show host on KFI-AM (640), surprising former adversaries with his mild manner. He also worked as a security consultant and had a few cameo roles in films.

When the chief’s job became available in 1997, he sent an electronic message to the city’s executive search firm indicating his interest.

“I did it just to get their juices going,” Gates later explained, adding: “I’m not sure I could get one vote.”

He was probably right about that. His refusal to give up the job during the King episode ultimately led to new provisions in the City Charter that gave the mayor and the Police Commission the power to select -- and remove -- the chief, who now has a term limit.

Along with civilian oversight, the drive to overhaul the LAPD provided an ironic last chapter in his legacy. A department assailed for an insular culture that tolerated racist officers entered a new era of accountability. Of the four chiefs who followed him, two have been African American. Citizen complaints received more thorough review in a new system that, to the consternation of many officers, left few gripes unexamined. And the concept of policing in partnership with the community -- a concept fostered by Chief Davis, implemented by then-Assistant Chief Gates and later gutted by Chief Gates -- returned as a centerpiece of the department’s operations.

Gates’ survivors include a son, Scott; two daughters, Debby and Kathy; a brother, retired LAPD Capt. Stephen Gates; and a number of grandchildren. Memorial services are pending.

Times staff writer Hector Becerra contributed to this story.

Malnic is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.