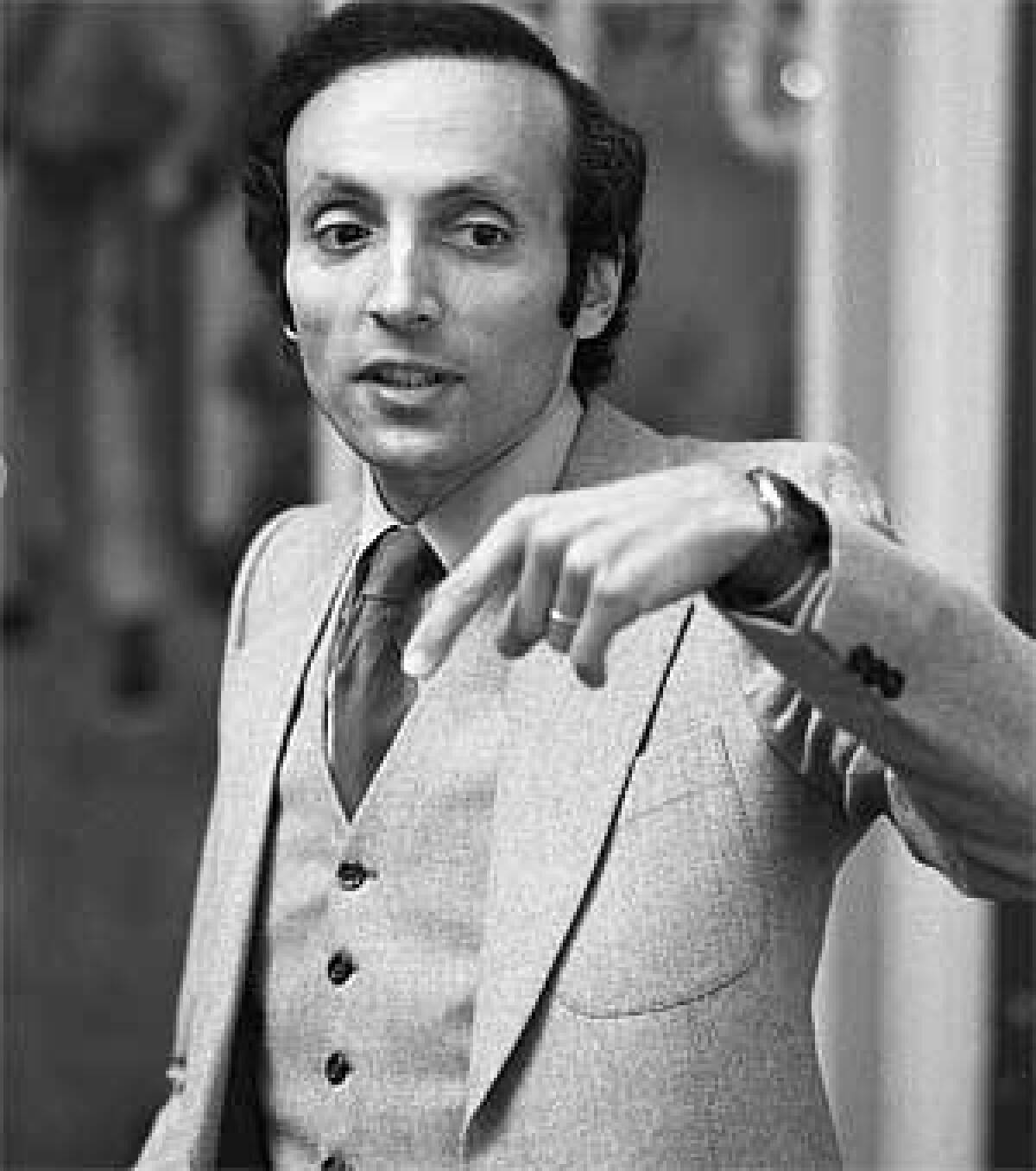

Erich Segal dies at 72; author of ‘Love Story’

- Share via

Erich Segal, a Yale University classics professor whose first novel, the weepy “Love Story,” became a pop-culture phenomenon, selling more than 20 million copies in three dozen languages and spawning an iconic catchphrase of the 1970s, died Sunday in London. He was 72.

Segal had Parkinson’s disease and died of a heart attack, his daughter, Francesca Segal, told the Associated Press.

“What can you say about a 25-year-old girl who died?” Segal wrote in the first line of the 1970 novel about star-crossed lovers, played in the blockbuster 1970 movie by Ali McGraw and Ryan O’Neal. The most famous line, uttered early in the film by McGraw’s character and later by O’Neal’s character, was “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

The sentimental romance provoked vales of tears and turned its author into a sensation practically overnight. His success unleashed “egotism bordering on megalomania,” as Segal said of himself, that helped set off a backlash: He was denied tenure at Yale and “Love Story” was ignominiously bounced from the nomination slate of the National Book Awards after the fiction jury threatened to resign.

“It is a banal book which simply doesn’t qualify as literature,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and fiction jurist William Styron.

The National Book Award for fiction that year went to Saul Bellow for “Mr. Sammler’s Planet.”

Segal nonetheless continued to write, operating on two planes. He produced eight more works of popular fiction, including “Oliver’s Story” (1977), “The Class” (1985) and “Doctors” (1987). He also wrote the academic tomes “Roman Laughter: The Comedy of Plautus” (1987) and “The Death of Comedy” (2001).

Segal taught at Princeton University, Dartmouth College and Brown University and was a visiting fellow at Wolfson College at Oxford University.

The son of a rabbi, Segal was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., on June 16, 1937.

According to a 2008 essay by his daughter in Granta magazine, his early childhood was somewhat lonely: For the first six years of his life, he lived with his ailing grandmother and grandfather because his parents’ apartment building did not allow children.

Left in the care of nannies, he wrote and performed his own plays, which, Francesca Segal wrote, “served the dual purpose of creating a cast of characters he cared about, and making the cast of his own life care more about him.”

His father wanted him to become a rabbi, but Segal had other plans. He went to Harvard and graduated in 1958 with the dual honors of class poet and Latin salutatory orator.

While completing his doctorate at Harvard, he became a lecturer at Yale in 1964, earned his doctorate in 1965 and by 1968 had risen to associate professor of classics and comparative literature.

As a release from the academic grind, he co-wrote with Joe Raposo a musical comedy called “Sing, Muse!” which ran off-Broadway for 39 performances. The reviews brought Segal to the attention of an agent, who helped him secure film work.

Segal co-wrote the screenplay for the Beatles’ movie “Yellow Submarine” (1968), which fulfilled a childhood dream of becoming a Hollywood writer. Segal found himself flying back and forth to London and hobnobbing with John Lennon.

He wrote “Love Story” as a screenplay but was persuaded by his agent to turn it into a novel. It went through 21 hardcover printings in the first 12 months, and the first paperback run of 4.3 million copies was said to be the largest initial print order in publishing history.

A slender 212 pages, “Love Story” revolves around the attraction between Oliver, a patrician Harvard hockey player, and Jenny, a working-class Radcliffe girl who ultimately dies of a mysterious disease.

It struck a chord that critics had difficulty deciphering. Nora Ephron, writing in Esquire, said the book’s overwhelming popularity was “something of a mystery.” But the chaste romance (it had no overt sex scenes) apparently had wide appeal in a culture that had lost its moorings in the wake of student protests, civil rights marches, assassinations, sexual revolutions and drug experimentation.

Segal himself may have offered the best explanation of its success. In a 1970 Time magazine interview, he said: “It’s awfully short. It’s unabashedly sentimental. But before the end I cried and cried and cried -- for 45 minutes. Then I washed my face and finished the book.”

The author became the darling of talk shows. He appeared on Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show” four times in four weeks. He happily answered the clamor for interviews, offering statements that came back to bite him. He bragged about his popularity with his students, calling himself “kind of a folk hero at Yale.” He compared himself to Shakespeare and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

His “never having to say you’re sorry” line was so readily absorbed at the lower reaches of the culture that it inspired takeoffs, such as the Santa Barbara dry cleaner that advertised its services on a sign that said “Bringing your clothes to us means never having to say you’re soily.”

Even O’Neal, whose star had risen with the “Love Story” movie, mocked it in the 1972 comedy “What’s Up, Doc?” with Barbra Streisand. When her character repeats the famous line, his character responds, “That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard.”

One of Segal’s few defenders was novelist Kurt Vonnegut, who told a Harvard audience that bashing “Love Story” was like “criticizing a chocolate eclair.”

After he was denied tenure at Yale, Segal moved to Europe. He married an English book editor, Karen James, in 1975. She survives him along with two daughters.

Segal grew more cautious of celebrity, choosing to live in London for most of the last three decades. His famous first novel, he told The Times some years ago, “shot me out of the box. Totally ruined me. . . .

“But I’m not going to say I’m sorry.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.