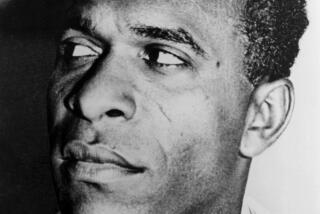

Fouad Ajami, Lebanese-born scholar, author and commentator, dies at 68

- Share via

Fouad Ajami, a Lebanese-born scholar, author and commentator who helped shape American discourse on Middle Eastern affairs with lyrical portraits of the troubled region that illuminated Arab consciousness and politics, died of cancer Sunday at his home in Maine. He was 68.

His death was announced by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where he was a senior fellow since 2011.

An adviser to the George W. Bush administration, Ajami strongly supported the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, a stance that made him either famous or infamous depending on one’s opinions. One critic described him as “an alienated Arab intellectual” who espoused Western conservative political values.

He wrote eloquently about Iraq in his 2006 book “The Foreigner’s Gift,” which critics said amply illustrated how important, if idiosyncratic, his voice was in the complicated debates over that country’s problems.

“He wasn’t in the mainstream, but you couldn’t ignore him,” Charles Hill, a Middle East expert at Yale University and former Reagan State Department aide, said in an interview Monday. “American discourse about the Middle East was not really on target ... pulled in one direction or another from both ends of the political spectrum. The result is people don’t really understand what’s going on. He was able through his powerful prose to point that out. And he was fearless in doing so.”

Ajami was disliked by some members of the Arab American community for using terms such as “tribal,” “atavistic,” “clannish” and “backward” to describe contemporary Arab politics. Edward Said, the Palestinian American cultural critic who died in 2003 accused him of “unmistakably racist prescriptions.”

Although controversial, Ajami was broadly praised for lucid and evocative writing. “He writes poetry, practically,” said former Secretary of State George P. Shultz, a Hoover Institution colleague who spent many hours talking with Ajami about the Middle East. “His information was firsthand. … He was somebody who was widely read whenever he published something.”

Ajami also was noted for “The Vanished Imam” (1986), about the controversial, Iranian-born Shia Muslim cleric Sayyid Musa al Sadr, who disappeared en route to a 1978 meeting with Libya’s Moammar Kadafi and “The Dream Palace of the Arabs” (1998), which examines the clash between modern ideals and ancient political realities through a series of essays on Arab writers.

Critics were particularly stirred by his chapter on Khalil Hawi, a Lebanese poet and icon of Arab nationalism who committed suicide on the day Israeli forces invaded his country in 1982. “Hawi, a man with whom Mr. Ajami clearly and strongly identifies, embodied the failed effort of the Arabic man of letters to create the ground for an Arab revival,” Richard Bernstein wrote in the New York Times of Ajami’s “important and illuminating” book.

Ajami was descended from tobacco growers who belonged to the minority Shia sect; his great-grandfather immigrated to Lebanon from Iran in the mid-1850s. He was born Sept. 9, 1945, in Amoun, a small village in south Lebanon near the border of what is now Israel. He grew up secular in Beirut.

At 13, he was swept up by talk of Arab nationalism and took a bus to Damascus to hear Egyptian leader Gamal Abdul Nasser speak about the movement. “It was a time of innocence. Around the corner, it was believed, lay a great Arab project, and this leader from Egypt would bring it about,” Ajami wrote in “The Dream Palace of the Arabs.”

In 1963, a few days before his 18th birthday, he left with his family for the U.S. He attended Eastern Oregon College before earning a doctorate in international relations from the University of Washington. He became a naturalized citizen in 1964.

He taught political science and international studies at Princeton University before moving to Johns Hopkins University, where he became director of Middle East studies in 1980. He won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1982.

During the period leading up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Ajami advised officials in the Bush White House on the benefits of regime change. He was quoted in a major speech by Vice President Dick Cheney, who cited Ajami’s conviction that liberation from Saddam Hussein’s government would cause the streets of Baghdad and Basra to “erupt in joy in the same way as the throngs in Kabul greeted the Americans.”

Ajami believed that removing long-standing autocracies was a necessary step toward stabilizing the region and would lay the groundwork for the growth of democracy and pluralism. In recent months, however, he voiced dissatisfaction with Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki for failing to unify the country since taking office in 2006.

He made frequent reporting trips to the Middle East, where he interviewed leaders as well as ordinary citizens. One of his last books was “The Syrian Rebellion” (2012), which New York Times reviewer Dexter Filkins called “an elegant and edifying book, written on the fly” about Syria in the midst of the historic upheaval that erupted in early 2011.

Ajami is survived by his wife, Michelle.

Twitter: ewooLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.