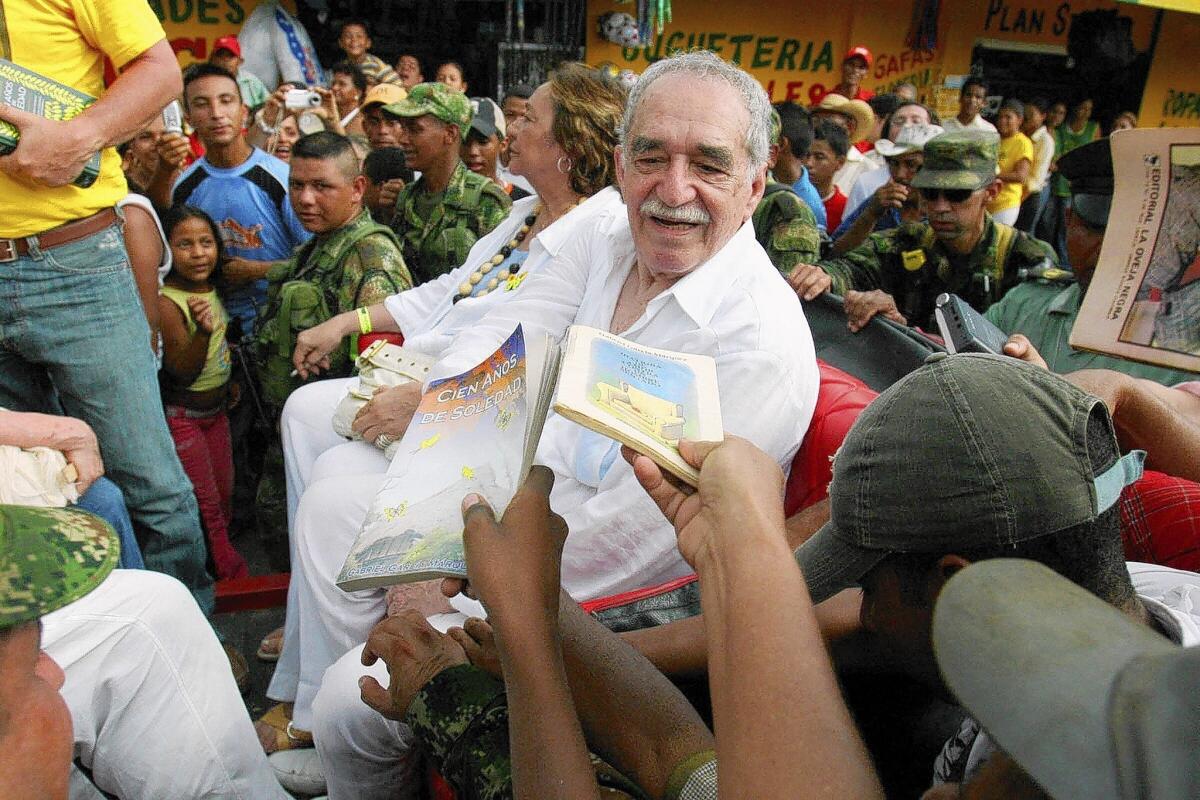

Gabriel García Márquez dies at 87; Nobel-winning writer was master of magical realism

- Share via

When Colonel Aureliano Buendía faced the firing squad, time slipped away, and his life became a dream. Before him rose the mythical town of Macondo and its retinue of gypsies and their pipes and kettle drums and magical inventions.

Of course Buendía’s dream belonged to the teller of the tale, Gabriel García Márquez, whose novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude” casts a spell upon readers that can never be broken.

A Spanish galleon lies in the jungle, its hull “an armor of petrified barnacles and soft moss,” its sails dirty rags, the rigging adorned with orchids. A child is born with the tail of a pig. Lovers tryst among butterflies and scorpions, and when it rains, it rains for four years, 11 months and two days.

FOR THE RECORD:

Gabriel García Márquez: An obituary of Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez in the April 18 Section A said he had published a memoir titled “Live to Tell the Tale” in 2001. The memoir, published in 2002, was titled “Vivir Para Contarla” in Spanish and “Living to Tell the Tale” in English.

García Márquez may not have invented magical realism, but he was its most adept practitioner, capable of mixing the transcendent and the bawdy, the whimsical and the tragic in equal proportions.

The 87-year-old Colombian writer died Thursday at his home in Mexico City, according to Rafael Tovar y de Teresa, president of the official Mexican cultural association.

The cause was not immediately announced, but Garcia Marquez had been in failing health for some time. He was released from the hospital just over a week ago.

The author of seven novels and numerous short stories and the winner of the Nobel Prize in literature in 1982, García Márquez filled his pages with the lives of dreamers, philanderers, anarchists, thieves and prophets, men and women driven by their appetites and often isolated by their folly. As fantastic as his fictions were, they were never far from reality.

In his speech to the Swedish Academy, García Márquez recounted the tragedy of Latin America, “that boundless realm of haunted men and historic women, whose unending obstinacy blurs into legend.” He talked about the wars, the military coups, a dictator intent upon “ethnocide” and of all the missing and imprisoned.

“A reality not of paper,” he said, “but one that lives within us and determines each instant of our countless daily deaths, and that nourishes a source of insatiable creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but one cipher more, singled out by fortune.”

He was known to his admirers as “Gabo,” and his influence helped fuel what is known as the “Boom,” the international popularity of Latin American literature in the years after World War II.

“Being a contemporary of Gabo was like living in the time of Homer,” said Colombian writer Héctor Abad Faciolince. “In a mythic and poetic way, he explained our origins. His verbal imagination and creative force were astonishing.”

Novelist Isabel Allende first read “One Hundred Years of Solitude” in Spanish in the mid-1960s and found her life, growing up in Peru and Chile, mirrored in its stories.

“It was a hurricane of ideas, images and voices,” she said. “It was my family and my grandfather. It was a way of explaining Latin America to the world — and to ourselves.”

Edith Grossman, who has been his translator since 1985, described García Márquez as “an alchemist.”

“The man writes like an angel,” she said. “He is so deft in his use of language, and he is so profound in his perception of emotions and the psychology of his characters. That combination is extraordinary.”

Grossman doesn’t like to refer to his work as magical realism. “He uses fantasy in a way that writers always have,” she says. “He uses fantasy to tell the truth; that is what literature does. It tells the truth through invention and make-believe. The magic comes from encountering a writer of genius who turns everything he touches into gold.”

Even though García Márquez’s blending of fantasy and outrageous facts “told with a straight face,” as he once put it, was pioneered by Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, Mexico’s Juan Rulfo and Argentina’s Jorge Luis Borges, he lifted the technique from obscurity with the publication of “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

Even today as the surprise and power of magical realism have waned, García Márquez continues to be influential.

“His voice is in the heart and mind of every writer in Latin America, even if you react against him,” said Allende. “Younger writers abhor magical realism and want to be as far away from García Márquez as possible, but again he is still the measure.”

The 1967 novel — “Cien Años de Soledad” — was published shortly before he turned 40. Until then, he had scraped by as a newspaper reporter, advertising copy writer and screenwriter. He was so poor that he had to mail the manuscript to his Argentine publisher in two packages because he couldn’t afford to send it all at once.

Known for his opinions on Cuba, military dictatorship and Latin American cultural autonomy, García Márquez counted among his friends Bill Clinton, French President Francois Mitterrand and the dictators Omar Torrijos of Panama and Fidel Castro of Cuba.

Although he faced harsh criticism for his friendship with Castro, who jailed hundreds of dissidents including writers for exercising the same freedom of expression that he gloried in, he was unapologetic. “I have many friends in the world, and they have been reduced to one,” he said, chastising Americans for their “pornographic obsession” with the Cuban leader.

His lifelong fascination with power — and dread of its confinement and isolation — inspired two other masterpieces. “The Autumn of the Patriarch” is the 1975 story (told in one 297- page paragraph) of a vile, uneducated despot who rules a Caribbean nation for two centuries. In “The General in His Labyrinth,” he re-creates the journey of the Latin American liberator Simón Bolívar, who was exiled to the Colombian port town of Santa Marta, where he died.

Like Pablo Neruda, Carlos Fuentes and other great Latin American writers, García Márquez was outspoken about the troubled politics of the region. After Chile’s socialist president Salvador Allende was overthrown in a 1973 military coup backed by the CIA, he vowed not to publish another novel until dictator Augusto Pinochet was deposed, but it was a difficult promise to keep. Following the publication of the “The Autumn of the Patriarch,” he wrote “Chronicle of a Death Foretold” in 1981, a fictional account of a small-town murder based on the brutal slaying of a family friend.

García Márquez worked steadily as a journalist and financed two Colombian magazines. With help from wealthy donors including Mexico cement king Lorenzo Zambrano, he underwrote a journalism foundation based in Cartagena to teach young writers reporting and storytelling skills.

His 1995 “News of a Kidnapping” was the true tale of the abduction and abortive rescue of four prominent Colombians, a book that conveyed the fear and terror that gripped his native country during the turbulent years of the notorious drug barons.

He later became a harsh critic of Plan Colombia, the U.S. military aid plan to fight drug cartels and a rebel insurgency, even though the $7-billion program has been credited with saving Colombia from becoming a failed state.

His fiction endeared him to millions of readers. Translated into more than 30 languages, “One Hundred Years of Solitude” has sold more than 20 million copies. The first printing sold out within a week.

He first tried writing the novel when he was 20, but he was 38 when he imagined the famous opening sentence with Buendía facing the firing squad and remembering the time his father took him “to discover ice.” At the time, García Márquez was driving with his family from their home in Mexico City to an Acapulco vacation and turned the car around and headed back to the capital to start writing.

Neruda, the Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet, called the novel “the greatest revelation in the Spanish language since the ‘Don Quixote’ of Cervantes.”

The name Macondo, which García Márquez appropriated from a banana plantation near Aracataca, has entered the lexicon to describe an exotic or surreal place. At his birth on March 6, 1927, the boom town was surrounded by banana plantations controlled by United Fruit Co. When García Márquez was a year old, nearly 1,500 striking United Fruit workers were killed by Colombian armed forces acting at the U.S. company’s bidding.

“The Massacre of 1928” remained largely obscure until García Márquez’s fictionalized account, which became a chilling counterweight to the book’s hallucinatory enchantments.

He was the first child of Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguaran, the daughter of a retired, well-connected colonel who had fought in Colombia’s War of the Thousand Days. García Márquez’s father, Gabriel Eligio García, was a relentless Don Juan and would-be medical student, forced by economic necessity to go to Aracataca as a telegraph operator. His grandfather, the colonel, opposed the courtship, and the stubborn passion that followed formed the plot of García Márquez’s 1985 novel, “Love in the Time of Cholera.”

Not long after García Márquez was born, the young couple moved to the coast, and nearly penniless, left “Gabito” with his grandparents and the three aunts who lived with them. García Márquez would call his grandmother — who talked of spirits and ghosts and spoke of dead ancestors as if they were still alive — “the most important figure of my life.”

At 9, he was reunited with his parents in a town called Sucre, where his father had established himself as a pharmacist. His family would grow to 15 children, including four of his father’s offspring born to other women but raised by his mother.

In Sucre, García Márquez met his wife to be, Mercedes Barcha, a teenage daughter of a family of Egyptian origin, whom he married in 1958.

Winner of a scholarship to a prestigious boys’ high school in Zipaquirá near the capital city of Bogotá, García Márquez showed early promise. He published his first short story as a 20-year-old student at National University in Bogotá and soon abandoned his law studies in favor of newspaper jobs. He published his first novel in 1955.

García Márquez’s radical leanings were shaped in part by “La Violencia,” the political convulsion that was touched off by a 1948 political assassination in Bogotá. U.S. support of right-wing Latin dictators and interventions, including the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, pushed him further to the left.

A disciplined writer, he would awaken each morning at 5 a.m., and as his wife slept beside him, he read from a nearby pile of books and made corrections on what he had written the day before. He would shower at 8, using the occasion to dream of characters and write sentences in his mind. He even had to install a second hot-water heater to support his habit.

Then he would dress, often deliberating over what to wear. “Of course all of this is a pretext because of the fear of going to write,” he once told a reporter.

After being diagnosed with lymphoma in 1999, he underwent treatment at UCLA Medical Center. The author also had a malignant lung tumor removed in 1992. He published a memoir, “Live to Tell the Tale,” in 2001, and his last novel, “Memories of My Melancholy Whores,” in 2004.

In addition to his wife, García Márquez is survived by sons Rodrigo, a Hollywood film director, and Gonzalo, a painter who lives in Mexico.

In accepting his Nobel Prize, García Márquez quoted William Faulkner’s famous line, “I decline to accept the end of man,” and put the burden on writers to imagine what’s possible, even in the light of the tragedy and despair.

“… we, the inventors of tales, who will believe anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of the opposite utopia,” he said. “A new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to one hundred years of solitude will have, at last and forever, a second opportunity on earth.”

Special correspondent Chris Kraul reported from Bogota. Times staff writer Tracy Wilkinson contributed from Mexico City. Former Times staff writer Anne-Marie O’Connor contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.