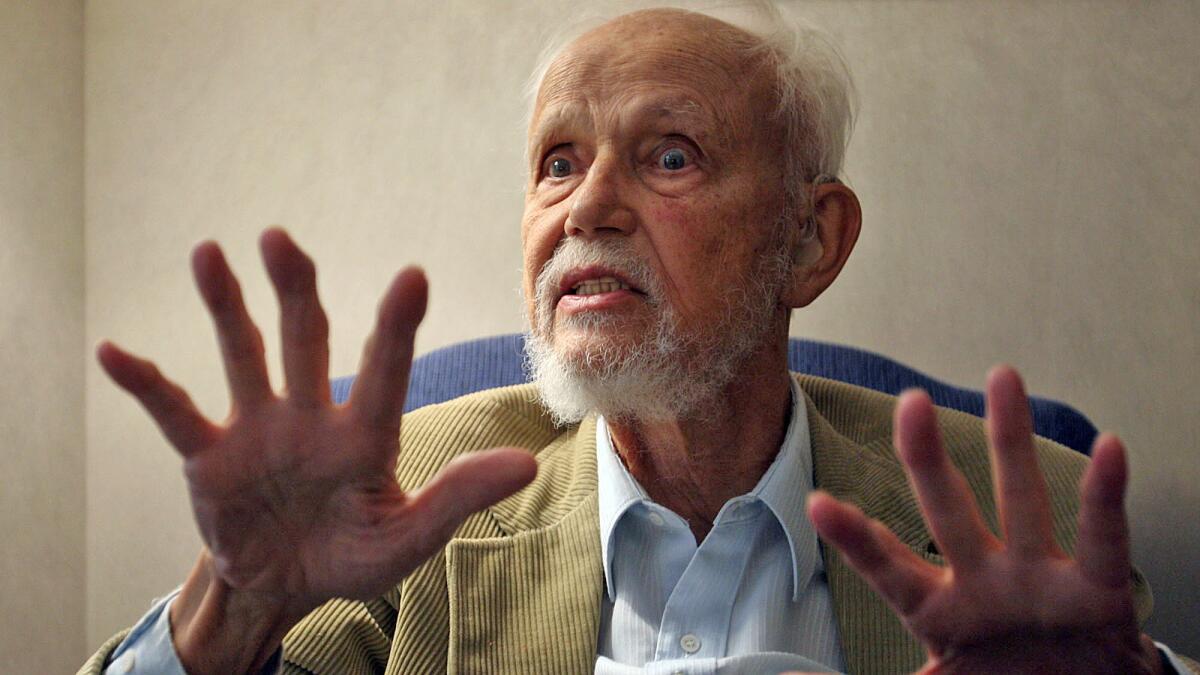

Huston Smith, pioneering teacher of world religions, dies at 97

- Share via

Huston Smith, a pioneering teacher of world religions whose knowledge and respect for the traditions of the major faiths attracted millions of readers, has died. He was 97.

Smith died at his home in Berkeley on Dec. 30 after a long illness, according to his official website.

From the time he was in his 20s, Smith immersed himself in the practices of many faiths, studying the Hindu Upanishad texts in India, living with Zen Buddhists in Japan, keeping the Muslim monthlong fast of Ramadan and observing the Jewish Passover. Well into old age, Smith made Hatha yoga part of his daily spiritual practice. But, as the son of Methodist missionaries noted some years ago, “I never canceled my subscription to Christianity.”

He wrote more than a dozen books, including the 2009 memoir “Tales of Wonder,” but his best-known work remained a survey text, “The Religions of Man,” first published in 1958. It was reissued as “The World’s Religions” in 1991 and has sold about 2 million copies.

His informed yet accessible prose led many laymen to read his books as their introduction to religions of the East and West.

“Huston was unique,” journalist and commentator Bill Moyers once told The Times. “He spent his life trying to penetrate the essence of the world’s religions, not only to understand them intellectually but to experience their particularity.” Moyers featured Smith in a 1996 PBS special “The Wisdom of Faith With Huston Smith.”

“His writings communicate powerfully that this man’s interpretation is no academic exercise,” Moyers said of Smith. “He has been to the place he is describing.”

Smith’s lifelong interest in the world’s major religions led him far from the United Methodist Church where he was raised and where he remained an active member. He was a regular presence in inter-religious discussions throughout his long career.

He had an early insight into the future of religion in America when he recognized that the country’s expanding ethnic diversity would lead to greater curiosity about formerly unfamiliar traditions of various faiths.

He also saw the potential for conflict on a global scale. “Huston anticipated, almost prophetically, the ‘contest of narratives’ that embroils the world today, as the world’s landscape rapidly changes under the resurgence of conflicting faiths,” Moyers said.

Asked how to manage in such circumstances, Smith told Moyers, “We listen. We listen as alertly to the other person’s description of reality as we hope they listen to us.”

Smith often pointed out that the world’s major faiths have essential aspects in common, including an emphasis on compassion, a belief in the existence of the human soul and the reality of the divine. His views, however, were not always welcome.

In 1955, he hosted a television program about the major religions of the world that aired on educational television. The show offended some Christian leaders who rejected Smith’s parallels between Christianity and other religious teachings.

Decades later, his appearance in “The Wisdom of Faith With Huston Smith,” brought the opposite reaction.

“In one lifetime, the response went from ‘don’t watch it,’ to ‘everybody should watch it,’” Smith said of the contrast. “That signaled a real change in our culture’s attitude.”

As the study of the world’s religions became more widely available at the college level, some scholars began to see Smith’s approach as just one option. “Huston was a universalist, who made generalizations about all religions,” Wendy Doniger, a professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School, said some years ago in an interview with The Times. “He believed that all people have a religious nature and all religions share certain things in common. He said that people answer life’s big questions — Is there a God? Why do we die? — in similar ways.”

More recently, Doniger said, many professors of religion in secular schools teach the subject in a comparative, cross-cultural way. They don’t necessarily look for a common core, she said. Still, Doniger said, “There is a great deal of virtue and wisdom in his writing.”

Religion gives traction to spirituality

— Huston Smith

Born in Suzhou, China, on May 31, 1919, to Christian missionary parents, Smith spent the first 17 years of his life in that country, which he said most likely helped set him on his course as a scholar of comparative religion.

He finished high school at the Shanghai American school before he journeyed to the West to continue his education. He graduated from what is now Central Methodist University in Fayette, Mo., in 1940 and went on to attend UC Berkeley and the University of Chicago, where he earned a doctorate in 1945.

As an American college student fresh from rural China, Smith was fascinated by science and technology. Gradually, however, he became more cautious about science as the answer to all questions. Years later, when he was in his 70s, he wrote “Why Religion Matters: Arguing the Need for the Sacred in the Scientific World” (2000). In it, he argued that Americans now see technology as a replacement for the mysteries of life. He saw science and religion as compatible.

Smith married Eleanor Wieman — she later changed her name to Kendra — in 1943. In 1945, he became a professor of philosophy and religion at the University of Denver, where he remained for two years, until he was hired as an associate professor of philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis.

In 1948, he met English writer Aldous Huxley, who would play a crucial role in Smith’s intellectual development. Huxley introduced Smith to a swami in St. Louis, which led the young professor to immerse himself in Vedantic philosophy. He traveled to Japan to study with a Zen master, studied Buddhism in Burma and worked among Tibetan refugees in northern India.

In 1958, he ascended the academic ladder and became a professor of Asian philosophy at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he arranged for Huxley to deliver a lecture series. Smith had been fascinated by Huxley’s account of his mystical experiences with mescaline in “The Doors of Perception” (1954) and asked how he could arrange to sample the drug himself.

Huxley referred Smith to “this interesting chap over at Harvard” — Timothy Leary.

On New Year’s Day in 1961, Smith swallowed two mescaline capsules at Leary’s home in Newton, Mass. Smith later said that the experience helped him understand the biblical claim that no one can see God and live. He compared the drug-induced mystical vision to “plugging a toaster into a power line.”

In 1965, his article “Do Drugs Have Religious Import?” was published in the Journal of Philosophy and became one of the journal’s most reprinted pieces.

He tried hallucinogens a few more times but, unlike Leary and fellow traveler Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass), he soon gave them up. “As Ram Dass told me,” Smith wrote in his memoir, “‘After you get the message, hang up.’”

Smith’s last full-time teaching position was at Syracuse University from 1973 to 1983. “Asia-wise, that decade brought Islam into my lived world,” he later recalled. He began to pray five times each day in the Muslim tradition.

He also produced award-winning documentary films about Hinduism, Tibetan Buddhism and Sufism, the mystical branch of Islam.

On retiring from Syracuse, Smith and his wife moved to Berkeley, where he taught part time until the mid-1990s.

In the 1990s, Smith turned his attention to Native American religion, New Age philosophy and the care of the environment. He spoke out in defense of Native Americans when the U.S. government outlawed the use of peyote for religious rituals in 1990. The court decision was reversed four years later.

His ongoing spiritual quest made him a popular workshop leader at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, a home for the human potential movement since the 1960s.

He was sometimes referred to as a “spiritual surfer,” but in public lectures, Smith came down firmly in favor of commitment to a religious tradition as an essential part of a spiritual practice.

“Religion gives traction to spirituality,” he told a crowded lecture hall at UCLA in 1999. “Speaking for myself, it is good to have a grounding of perceptible depth in one of the religious traditions.”

Put another way, he said, “If you are looking for water, it is better to drill one 60-foot well than 10 six-foot wells.”

In addition to his wife, Smith is survived by his brother, Walter; his daughters Gael and Kimberly; and three grandchildren. His oldest daughter, Karen, died of cancer in the mid-1990s.

Rourke is a former Times staff writer.

ALSO

D.A. backs man who insists he was wrongfully convicted of notorious Palmdale murder

Alexa may be listening, but will she tell on you?

UPDATES:

9:35 a.m.: This article was updated with additional details on Smith’s death

This article was originally published at 8:05 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.