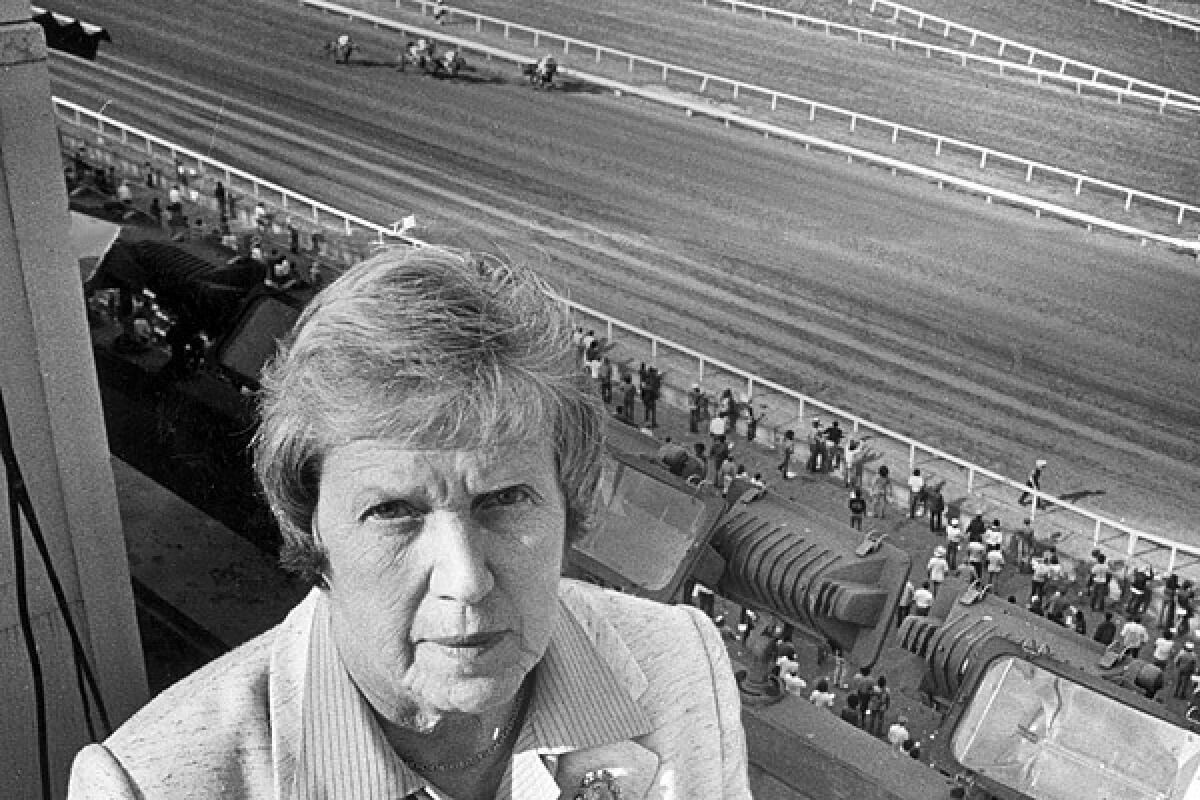

Marje Everett dies at 90; legendary figure in horse racing

Notable deaths of 2011

- Share via

Marje Everett, a legendary and controversial figure in the sport of horse racing for more than four decades and the chief executive of the Hollywood Park racetrack for six years, has died. She was 90.

Everett’s longtime associate, Dorothy Carter, said Everett had been in declining health the last year and died Friday morning at her Los Angeles residence.

Everett became a major female force in sports at a time when it wasn’t considered a possibility. When she lost a takeover battle with businessman R.D. Hubbard for control of Hollywood Park in 1991 — after turning away several other bids in previous years — she had been a director at the Inglewood track since 1972 and its chief executive since 1985.

Before that, she had owned and operated Washington and Arlington parks and Balmoral Track in Chicago. When those were purchased by Gulf and Western in 1968, she stayed as top manager at the request of Gulf and Western officials, but after a year was asked to step down. As part of that deal, she was given stock worth 10% of Hollywood Park.

From the moment she arrived until the day she left, she was an undeniable force in a sport that, for much of her time, was in its prime. In 1984, for example, Hollywood Park’s revenue was $74 million. That was the year of the initial Breeders’ Cup, then and now a showcase of top racing for enormous purses. The current Breeders’ Cup has as its grand finale the Classic, worth $5 million.

When the initial Breeders’ Cup organizers narrowed the host sites to Santa Anita or Hollywood Park, Everett battled to get it to her track. During the decision-making, she made a personal contribution of $200,000 to the Breeders’ Cup. The Oak Tree Assn., which was trying to host that first Breeders’ Cup at Santa Anita, was critical of Everett. Her response was typically crusty.

“I have little regard for most of the people at Santa Anita,” she said, in an interview with Times horse racing writer Bill Christine. On the same issue, about another opponent, she said, “I will never bury the hatchet.”

Still, many horsemen remember her for her love of the sport, her drive for it to prosper and her vision for it. She was usually the first to arrive at the track in the morning. In a 1969 interview in Sports Illustrated, well before racing had sold its future and soul to off-track betting, Everett said, “I insist that the mutuels [betting handles] are of secondary importance to the attendance at the track. Build your attendance, and everything else, including the mutuel handle, will fall into place.”

She was the daughter of Ben and Vera Lindheimer. Lindheimer was a wealthy real estate executive and Chicago politician who owned horses and eventually owned Arlington, Washington and Balmoral. Everett was one of their three adopted children. She was born June 8, 1921, in Albany, N.Y., adopted at age 1 and said years later that she had known and forgotten her birth name, “because it was on a piece of paper somewhere and I lost it.”

Quickly, it became clear she was the child most interested in carrying on the Lindheimer racing pursuits. She would spend hours at the track with her father and loved everything there — even when her father fired her from her first job as a phone operator because her voice wasn’t friendly enough.

From the start, she was involved in everything her father did. In the 1940s, he was part-owner, along with Bing Crosby and Don Ameche, of the Los Angeles Dons of the All-American Football Conference. She did player acquisition and even recently spoke glowingly of the fledgling league.

When Ben Lindheimer died in 1960, Everett took over and ran the Chicago racetracks. She brought bigger purses, bigger races and, eventually, night racing. She hired people faster than she fired them, and that was pretty fast.

Controversy did not escape her.

In the late 1960s, Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner was indicted and eventually jailed for taking bribes. One version had Everett admitting to officials that she had given Kerner stock in the track in exchange for better racing dates and freeway ramps. Another version said that prominent Illinois racing official William S. Miller had pressured Everett to give favorable track stock prices to Kerner.

As recently as two years ago, Everett characterized her role in the Kerner case as “little more than a witness” and angrily rejected the characterization of her as an unindicted co-conspirator.

In 1958, when Everett was 37, she married Webb Everett, who became general manager of Golden Gate Fields in the Bay Area. He was 61 at the time and died in 1977. She has no immediate survivors, according to Carter.

Once in charge of Hollywood Park, Everett made it a welcome place for the stars. The important racing days were packed with celebrities, and Everett used them for image and public relations. At one opening day, she reserved a prime table in the Directors’ Room for Elizabeth Taylor, Michael Jackson and the sports editor of the Los Angeles Times.

Included among her closest associates over the years were Ronald and Nancy Reagan, Angie Dickinson, Cary Grant and John Forsythe. It was standard fare at her parties to have Jimmy Stewart sit down at the piano and sing a few tunes.

In 1978, despondent over the recent death of his wife, actor Charles Boyer killed himself with a drug overdose at Everett’s home in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Her fondness for racing, and especially for jockeys, never waned. When Bill Shoemaker crashed his car and was left paralyzed, Everett was among the first at the hospital. Laffit Pincay Jr., among the winningest jockeys ever, said Friday, “She was one of my best friends. I admired her because she was 100% for racing.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.