Stanley Rubin dies at 96; prolific writer-producer of TV and film

- Share via

There was a 69-year gap between the time that Stanley Rubin enrolled at UCLA in hopes of launching a writing career and 2006, when he actually graduated.

And during that seven-decade break in schooling, the prolific film and television writer and producer left his mark at nearly every studio in Hollywood, helped run the Writers Guild and Producers Guild and took home one of the first Emmys ever awarded.

Rubin, 96, died Sunday in his sleep at his home above the Sunset Strip, said actress Kathleen Hughes, his wife of 59 years.

Born Stanley Creamer Rubin on Oct. 8, 1917, in the Bronx, he was a teenager when he took a Greyhound bus across country to enroll at UCLA in 1933. After working as the editor of the school’s Daily Bruin newspaper, he was a few units shy of graduating when he dropped out in 1937 to work for a weekly Beverly Hills newspaper owned by Will Rogers Jr.

From there he went to work in the Paramount Pictures mailroom, where his radio, TV and film career was launched. In 1949, the first year Emmys were awarded, he accepted the statue for best film made for television for an episode of “Your Show Time” episode titled “The Necklace.”

By 1940 he had become a writer at Universal Studios; in 1946 he switched to Columbia Pictures, and in 1948 he moved to a producing job at NBC-TV. Rubin worked as a theatrical film producer for a variety of movie studios in the early 1950s before returning to television producing at CBS-TV. He moved back to TV production at Universal Studios in 1960, morphed to a TV producing post at 20th Century Fox in 1967 and then at MGM Studios from 1972 to 1977.

Along the way, he wrote 19 movies and produced more than two dozen feature and TV films including a 1955 Francis the Talking Mule comedy and James Coburn’s breakthrough role in 1967’s “The President’s Analyst.” Producing “River of No Return” in 1954, Rubin turned into a diplomat when he mediated between strict director Otto Preminger and mercurial star Marilyn Monroe.

After leaving MGM, he worked as an independent film producer. His last screen credit in 1990 was as co-producer for Clint Eastwood’s “White Hunter Black Heart.”

Hughes said her husband’s favorite movie was “The Narrow Margin,” a 1952 thriller about assassins stalking a woman taking a train from Chicago to Los Angeles to testify against the mob.

The movie’s release was delayed when RKO Radio Pictures head Howard Hughes became enthused by the film and asked Rubin to reshoot it with an A-list cast instead of Marie Windsor starring as the woman and Charles McGraw playing a police detective trying to protect her. Rubin refused on grounds that the whole film would have to be recast and reshot.

Rubin could be stubborn when he stood up to studio chiefs, recalled a friend, film historian Alan K. Rode. He once refused when another studio head insisted that a fictional movie about Adolf Hitler escaping Nazi Germany and hiding in the U.S. be changed to a film about communists making nerve gas in the Midwest, said Rode, director of the Film Noir Foundation.

During World War II, Rubin served a stint with the Army’s First Motion Picture Unit. He hammered out contracts for the Writers Guild and spent five years as president of the Producers Guild.

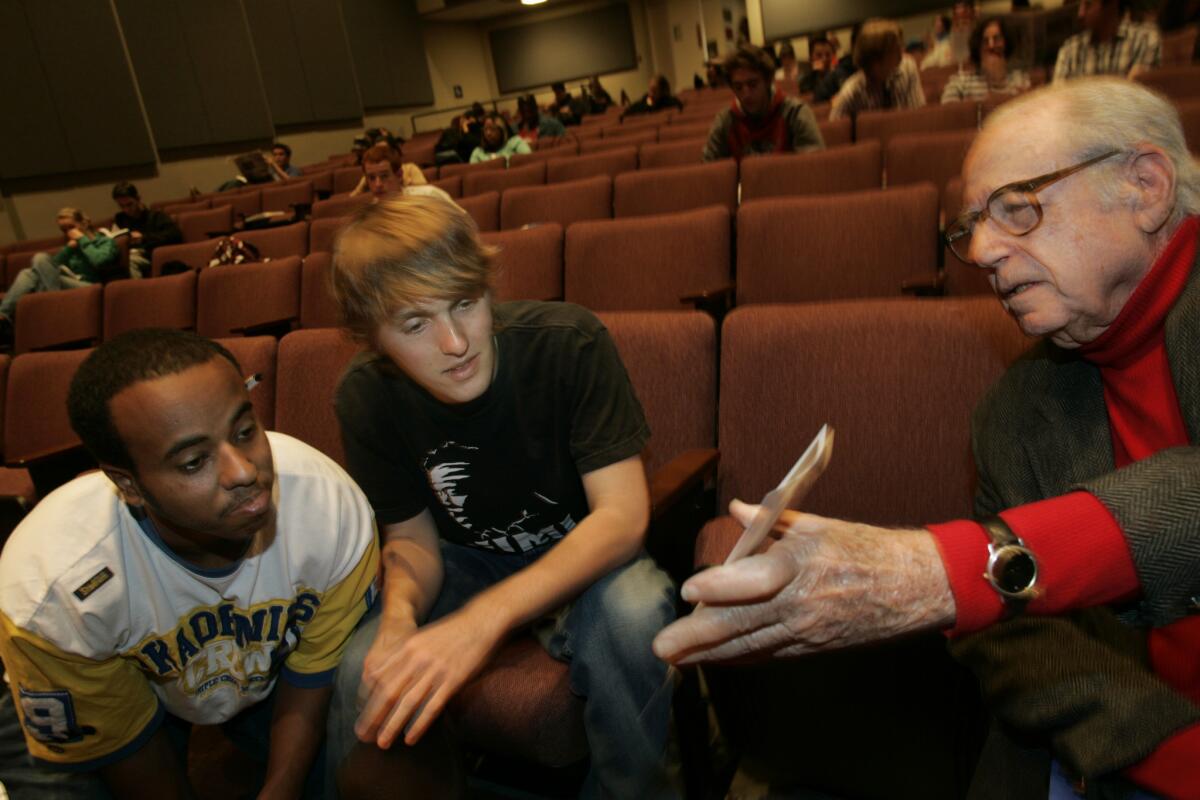

Rubin’s decision to return to UCLA to make up his missing 14 units found students in a 2006 School of Theater, Film and Television history class in awe of him after they discovered who he was. They were shocked to learn that the grandfatherly man who always sat near the front of the class had been a genuine pioneer of radio, television and film.

Rubin’s 20-page term report was about how advertisers, not networks, determined the content of 1940s radio shows.

“Most of the scripts I wrote ran about 120 pages,” he confided to one of his young classmates. “So this was a piece of cake. But don’t tell the professor.”

Besides his wife, he is survived by daughter Angie, a film music editor; sons John, a documentary filmmaker; and Michael, who formerly worked in postproduction. Another son, Chris, died in 2008.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.