Vic Braden dies at 85; tennis coach was an ambassador for the sport

- Share via

Vic Braden wasn’t easy to slow down. Wherever tennis was being played or needed to be taught, Braden was there. That was especially the case around Southern California, where he made his headquarters, ran his camps, developed his teaching-tennis videos and wrote his teaching-tennis books.

At tennis tournaments spanning major events from Indian Wells to the U.S. Open in New York City, Braden’s presence was a given — either in the background of post-match news conferences filming the interviews or right in the middle of things, asking questions.

Braden, 85, died Monday at his home in Trabuco Canyon of complications from congestive heart failure. For years he had suffered from diabetes, and he lost the sight in his left eye a few years ago.

Braden was a Depression child. Born in Monroe, Mich., on Aug. 2, 1929 — two months before the Great Depression began in earnest — he was one of six children. His father worked in a paper mill and as a coal miner, and Braden loved to tell the story of how the poverty of those days led him into tennis.

“I got caught stealing tennis balls at school,” he once told Jack Neworth of the Santa Monica Daily Press, “and the man who caught me said I could either go to jail or learn to play tennis.

“That was a no-brainer.”

Braden, a short, stocky man, played all sports as a teenager but found his best success in tennis. He eventually became No. 1 player at Kalamazoo College.

He was good enough to join Jack Kramer’s pro tour in the early 1950s and stayed on that tour for three years. It was Kramer, for years the most powerful and influential person in the sport, who once said that, in his mind, Braden had done as much or more to engender interest in tennis as the likes of top-ranked players John McEnroe and Bjorn Borg.

Braden was forever upbeat.

When he was diagnosed with diabetes, he handled it in typical Braden fashion. He started developing programs for schoolchildren in Santa Ana that would teach them about nutrition and inspire them to eat better. And he personalized his fate with his ever-present quick quip and sense of humor.

“I was hoping to play in the 90-and-over division,” he said.

One of his teaching themes became a subject of conversation at this year’s U.S. Open, when Italy’s Sara Errani made a deep run into the women’s draw. Errani starts her service motion by resting her racket over her shoulder before she makes her toss and hits. That was a Braden no-no.

“No backscratchers,” he would tell his students, when teaching the serve. As Errani advanced, reporters speculated that Braden would be bristling.

He won many awards, including the International Tennis Hall of Fame’s Education Merit Award in 1974.

Next March, he was to receive the prestigious Alan King Passion Award at the BNP Paribas Tournament at Indian Wells.

“We had just decided two weeks ago that Vic would get it,” said Ray Moore, tournament chief executive. “This was a shock to us. We didn’t realize he was that ill. He was very private about things like that.”

Moore said the selection of Braden for his tournament’s main award was not difficult.

“He was a real icon,” Moore said. “He made great contributions to our sport.”

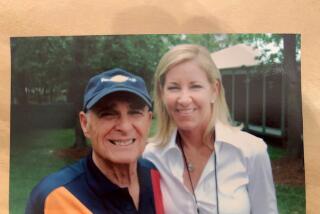

Braden’s wife, Melody, will receive the award on his behalf in a center court ceremony, Moore said.

Besides Melody, Braden is survived by children Kory Braden Hittleman, Kristen Paul, Troy Davis and Shaun Davis, plus four grandchildren. Another child, daughter Kelly, died 12 years ago from complications of lupus.

Twitter: @DwyreLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.