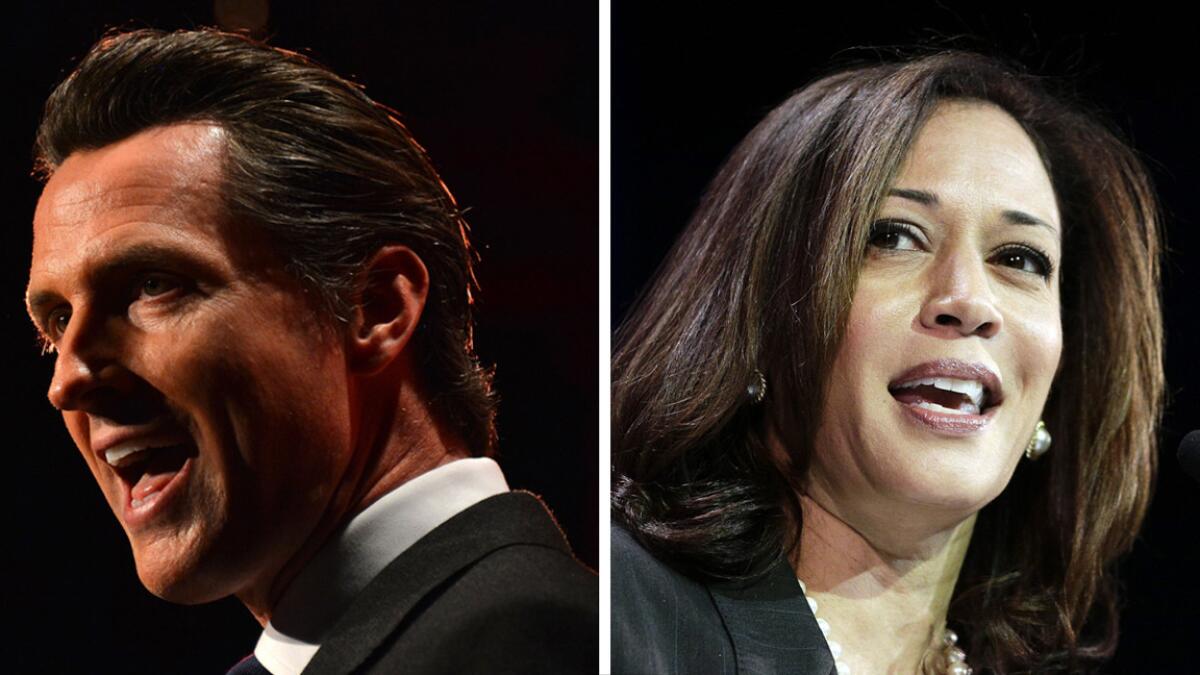

California GOP sees Democrats Newsom and Harris as sitting pretty

- Share via

Republicans trying to unseat Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom and Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris share a common complaint: The two Democrats are so confident of reelection that they’re already laying ground to run for governor in 2018.

“She’s looking right past us,” David King, a Harris challenger, told a recent gathering of Republican women in Thousand Oaks.

Newsom and Harris, two of the best-known Democrats on the June 3 ballot, insist they’re taking nothing for granted. Both deny they’re focused on 2018.

But the weak standing of their Republican challengers, all of them far behind in both fundraising and name recognition, is emblematic of this year’s lopsided and low-key California elections, with Democrats well-positioned to keep their grip on every statewide office.

It has also fueled speculation about whether a clash between Newsom, 46, and Harris, 49, the leading San Francisco politicians of their generation, is inevitable.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that they’re on a collision course for running for governor in 2018,” said Garry South, a former Newsom consultant who was chief political strategist for former Gov. Gray Davis.

Much can change in California’s election climate over the next four years. Among the biggest unknowns: Will Sen. Barbara Boxer, 73, seek reelection in 2016, and will Sen. Dianne Feinstein, 80, run for another term in 2018?

If either Senate seat opens up, the calculus could shift for Newsom, Harris, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and other Democrats weighing a run for governor.

For now, Newsom and Harris appear minimally engaged in the June 3 primary, apart from raising money that — if they don’t need it this year — can be rolled into a 2018 campaign.

“It seems remarkably quiet,” Newsom said. “It’s surreal.”

The torpor is due largely to the state’s highest-profile contest. No Republican or member of any other party, so far, is posing a serious threat to Gov. Jerry Brown. In the most recent Field poll, the Democrat was running a staggering 40 percentage points ahead of his top challenger, Republican Assemblyman Tim Donnelly of Twin Peaks, a tea party favorite.

Nationally, Republicans are in relatively strong shape as they try to recapture the U.S. Senate in a year when President Obama’s popularity is low. But in California, the huge fundraising lead that Newsom and Harris have each established over Republican rivals underscores how hard it is to bounce a Democrat from statewide office in the deeply blue state.

In March, when the most recent complete fundraising reports were filed, Newsom showed $1.9 million in cash on hand, and Harris $3.2 million. Since then, labor unions, lawyers, Silicon Valley executives, hedge fund managers and others have given an additional $171,000 to Newsom and $400,000 to Harris.

For Harris’ four Republican challengers, money has been harder to get. They reported a total of zero cash on hand in March. Two of Newsom’s were also empty-handed; the third had $62 in the bank.

Since then, the seven Republicans combined have reported raising just over $31,000, making it close to impossible for any of them — or for the six others on the ballot for attorney general or lieutenant governor — to mount a viable campaign in a state with nearly 18 million voters.

But they’re trying to make do.

At the Thousand Oaks golf club gathering, King and another Republican Harris opponent, former state Sen. Phil Wyman of Tehachapi, took turns bashing the attorney general’s record in remarks to members of Conejo Valley Republican Women Federated.

Wyman reminded the crowd of his proposal to punish elected officials convicted in corruption cases involving gun violence with execution by public hanging, firing squad or lethal injection. “That’s what I stand for, the rule of law,” he told the group.

King, a San Diego attorney active in local Republican politics, rolled his eyes when asked about Wyman’s long-shot candidacy. As for his own, he said: “I jumped in because we don’t have a credible candidate, and I don’t believe in surrendering a state.”

Former state Republican chairman Ron Nehring offered a similar rationale for his own candidacy for lieutenant governor.

“Gavin Newsom treats this office like it is a taxpayer-funded gubernatorial exploratory committee for 2018, and everybody knows that,” said Nehring, whose campaign road trip from San Diego to Santa Maria on Wednesday included a dinner stop at Pea Soup Andersen’s in Buellton.

For Harris, the non-campaign is a welcome reversal of fortune. In 2010, her victory margin was so narrow — less than 1% — that it took more than three weeks of vote counting to win a concession from Republican rival Steve Cooley, at that time L.A. County’s district attorney.

Nearly every law enforcement group in California had lined up against her after she refused, as San Francisco’s D.A., to seek the death penalty in prosecuting the killer of city Police Officer Isaac Espinoza.

But in her reelection run, Harris has won the support of police unions and prosecutors around the state, including the Republican district attorneys of San Bernardino and San Diego counties.

Her office affords Harris constant opportunities to reinforce her law-and-order credentials. She recently announced 41 arrests in San Joaquin Valley drug raids, with 200 agents seizing guns, methamphetamine, cocaine, marijuana, ecstasy and $83,000 in cash.

At a recent sex-trafficking symposium on the Westside, Harris recalled her work in the 1990s as an Alameda County prosecutor on homicide and child sexual-assault cases. “I’ve stood before many juries, talking about why there should be consequence and accountability,” she said.

Newsom’s job, with its limited powers, is often a struggle for relevance, particularly for a onetime San Francisco mayor who drew worldwide headlines a decade ago when he ordered the city to sanction same-sex weddings.

Tensions with the governor make matters worse: Brown has ignored Newsom’s plans for improving California’s economy.

Before abandoning his campaign against Brown in the 2010 primary for governor, Newsom mocked his rival’s quest to regain the job he’d first won in 1974 as a “stroll down memory lane.” In February, Newsom needled him further by withdrawing support for Brown’s prized high-speed rail project.

But Newsom, whose family ties with Brown run deep, is circumspect when talking about the governor.

“He and I have a good interpersonal relationship,” Newsom said. “But I think the dynamics of the governor’s office with a lot of offices, one could sort of analyze and reflect on.”

Looking ahead to 2018, Newsom said that although people around him and Harris assume that their ambitions create friction, “there’s no real competitiveness.”

“But invariably, in the future, that’s to be determined,” Newsom added. “There may be a point where that presents itself, but I don’t think about it much. And those that do, I tell them not to.”

Harris, who shares political advisors with Newsom, declined to talk about 2018.

“I am superstitious,” she said. “I believe you must do what’s in front of you, and do it well, and the next thing will come.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.