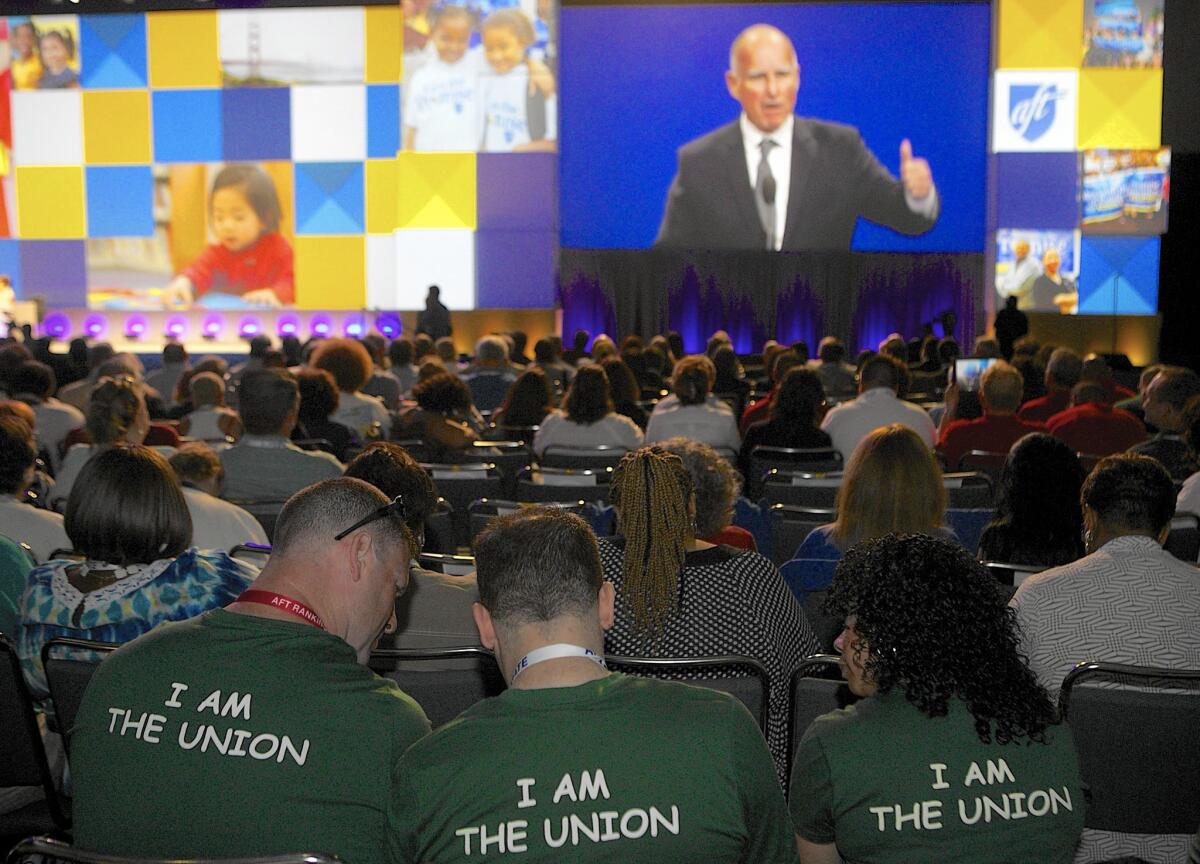

Unions remain a crucial backer of Gov. Jerry Brown’s campaign

- Share via

Reporting from SACRAMENTO — The proposal to restrict school districts’ financial reserves seemed to come out of nowhere, slipped into the state budget just days before the spending plan would come up for a vote.

At a legislative hearing, Democrats were confused and Republicans were critical. Recession-weary education officials launched an unsuccessful counterattack against the measure, pushed by California’s largest teachers union and inserted by Gov. Jerry Brown.

The June episode was a reminder that unions have often found a loyal friend in Brown, who has been allied with the labor movement since his political career began more than four decades ago.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Political spending: In the Oct. 23 Section A, an article about Gov. Jerry Brown’s relationship with unions misstated the amount of money Republican Meg Whitman spent in her 2010 campaign for governor. She spent $177 million, not $160 million.

------------

The governor has occasionally frustrated union leaders with budget cuts and intransigence at the negotiating table. But he has also delivered on many of their biggest priorities, prompting his Republican opponent, Neel Kashkari, to paint him as a tool of labor benefactors.

As Brown seeks a fourth term, unions remain a key element of his political power, providing millions of dollars in donations and deep ranks of campaign foot soldiers.

“We agree on a lot of the issues,” said Dean Vogel, president of the California Teachers Assn. “It’s not a big surprise we would be on the same page.”

Brown, for his part, “is doing what’s best for California,” said his spokesman, Evan Westrup.

Since Brown took office in 2011, labor has chalked up victories large and small.

A union representing cashiers successfully pushed limits on self-serve computers at grocery store checkouts. Unionized state employees received raises of 1.5% to 6% after several lean years. Infrastructure projects Brown is championing, such as new reservoirs and a bullet train, are expected to create thousands of union jobs.

The California Teachers Assn., a political powerhouse in Sacramento and one of the governor’s biggest financial backers, has scored several wins.

The new rule limiting school reserves, which will take effect if voters next month approve Proposition 2, the governor and Legislature’s bid to strengthen the state’s rainy-day fund, could free up more money for wages and classroom spending.

Brown agreed to a moratorium on teacher layoffs during the state’s budget crisis three years ago. And this year he appealed a controversial court decision that struck down some tenure rules.

Brown has helped other workers too. He signed legislation boosting the minimum wage to $10 an hour over the next two years, requiring that many domestic workers qualify for overtime pay and guaranteeing paid sick days for millions.

The governor acknowledged his affinity for labor in a March speech to the California Labor Federation, a coalition representing 2.1 million workers. He traced the connection to his childhood, when his father, Pat Brown, was a San Francisco prosecutor.

“I remember from the first time he ran for district attorney, he had the San Francisco building trades right there in the living room,” Brown said. “I know how important labor has been.”

He told union members they won’t always see eye to eye, but they should be patient: “If you don’t get the bill signed the first year … I’ll be around for the next five years.”

Indeed, Brown is considered a shoo-in for reelection. He leads Kashkari, a former U.S. Treasury official, by as much as 21 points in multiple polls.

Unions have contributed about $3 million to the governor’s $23.6-million reelection account and nearly $2 million to his campaign fund for the water bond and rainy-day reserve. They have also contributed to organizations such as the state Democratic Party that have given to Brown and his causes.

When Brown ran for governor in 2010, unions helped him counter a record-breaking $160-million campaign by GOP rival Meg Whitman, former eBay chief.

Rob Stutzman, a Republican consultant who worked for Whitman, said money spent separately from Brown’s campaign helped keep him from losing ground early in the race, when he was still building his war chest. Unions were part of the independent effort, spending $14 million on it before the summer was over.

“Their support was critical,” Stutzman said. “He never really fell behind.”

In 2012, Brown relied on unions to help pass Proposition 30, his temporary tax-hike measure. The Service Employees International Union, which represents healthcare workers, government employees and others, pitched in $4.3 million for the campaign, and the teachers union gave $10.3 million.

Their support went beyond money. The California Labor Federation used its sophisticated campaign operation to turn out voters in support of the tax hike.

“There’s nothing that substitutes for knocking on doors,” said Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor of history at UC Santa Barbara. “Unions can do that. And there’s not a lot of other groups that can do that.”

Although Brown is often aligned with unions, they’re not always on the same page.

During his first two terms as governor, from 1975 to 1983, Brown signed legislation allowing state workers to bargain collectively. Later he angered labor leaders by trying to block pay increases for them.

And since returning to the governor’s office almost four years ago, Brown’s fiscal policies have occasionally frustrated labor leaders.

Even though he softened his original proposals for overhauling California’s public pensions, public workers will contribute more toward their retirement benefits under changes he signed into law.

He demanded that home health aides who are paid through a state program be exempt from a new law guaranteeing paid sick leave, saying it would cost too much to grant them the benefit.

And he vetoed a bill that would have given the United Farm Workers more leverage in contract disputes.

“He’s not an automatic supporter,” said Art Pulaski, leader of the California Labor Federation. But “do we have a good relationship? Yes. He’ll always engage, he’ll always be open.”

Overall, Pulaski said, “We’ve had good luck with him, getting our bills signed.”

Brown recently came to labor’s aid after a U.S. Supreme Court decision that said home aides who don’t want to join a union don’t need to pay dues, even if their salaries and benefits are covered by union contracts.

The governor signed legislation giving labor representatives an extra recruiting opportunity in California: They’re now guaranteed time to meet with new home care workers during state-mandated orientation sessions.

“It’s absolutely an opportunity to talk about the work unions do for all of the workers they represent, and see if new workers want to join the union,” said Scott Mann, a spokesman for the SEIU. “It really will benefit the workers.”

Twitter: @chrismegerian

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.