California colleges see surge in efforts to unionize adjunct faculty

- Share via

A wave of union organizing at college campuses across California and the nation in recent months is being fueled by part-time faculty who are increasingly discontented over working conditions and a lack of job security.

At nearly a dozen private colleges in California, adjunct professors are holding first-time contract negotiations or are campaigning to win the right to do so. Those instructors complain of working semester to semester without knowing whether they will be kept on, lacking health benefits and in some cases having to commute among several campuses to make a living.

While union activists say they look forward to better working terms and a greater voice in how campuses are governed, many college administrators say they are worried that such union contracts could mean less flexibility in academic hiring and higher tuition costs.

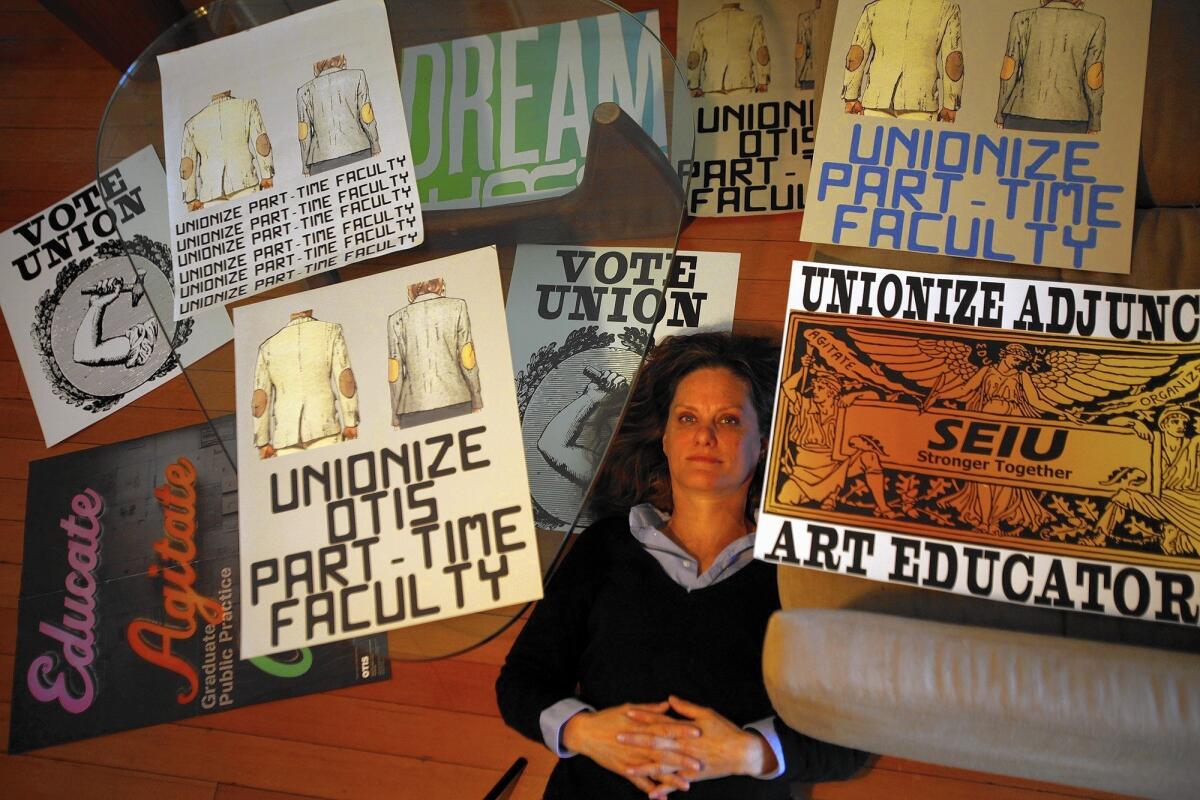

Service Employees International Union chapters in the Los Angeles area and in Northern California this week won faculty elections to represent part-time professors at Otis College of Art and Design in Westchester and Dominican University of California in San Rafael, and part-timers and non-permanent full-timers at St. Mary’s College of California in Moraga. In recent months, the union succeeded in hard-fought votes among part-time faculty at Whittier College, Mills College and California College of the Arts in Oakland, San Francisco Art Institute and Laguna College of Art and Design.

Andrea Bowers, who has taught one or two courses a semester at Otis for the last five years, said she typically is paid $3,000 for each class in public arts practice and other fine arts subjects plus $1,000 to mentor students’ studio work. She also juggles a professional art career and teaching assignments elsewhere.

“A living wage is really crucial,” she said. “It’s no surprise that the SEIU is simultaneously organizing McDonald’s workers and part-time college teachers.”

Beyond any improvements in pay and more predictability in knowing whether teaching jobs will last beyond the academic year, she said a union contract would force schools to be more transparent about their budgets. If colleges and faculty work together to solve financial problems, “that would be wonderful,” Bowers said.

The vote at Otis, announced Tuesday by the National Labor Relations Board, was 77 to 70, a smaller margin of victory than at most of the other schools. Jon McNutt, an attorney for Otis, said the close tally showed that there are “a lot of very strong opinions on both sides” about unionization, but he said that the college will accept the results and negotiate in good faith toward the first contract for part-time faculty.

The school’s online postings to faculty before the election described SEIU as “an outside organization that may not fully understand an institution like Otis.” The design college, which enrolls about 1,100 full-time students, sought to link the cost of union dues to substantial salaries for union organizers and spending on political campaigns.

Even as unions lose membership in other industries, they have found friendlier turf in academia. Outside California, organized labor has won recent elections at several large private institutions, including Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and Tufts in the Boston area.

New contracts for part-time faculty at those schools boost pay and, without guarantees, contain formal rules about notifying instructors in advance about teaching assignments and the length of contracts. Colleges seeking to avoid unionization contend those pacts are no better than what could be obtained without the unions. (Part-time and untenured faculty at many public universities, including UC and Cal State, long have been represented by unions.)

The unusual number of union campaigns springs from the use of more part-time instructors as a way to reduce the hiring of tenure-track faculty, said William A. Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions, at Hunter College in New York.

The pro-union response is coming from adjuncts who, he said, constitute “a large group of people who are highly educated, highly motivated and highly experienced.”

About half of U.S. college and university faculty were full-time in 2011, down from 77% 40 years before that, U.S. Department of Education data show. Part-time instructors teach about a fourth of all classes at research universities and more than a third of courses at community colleges, according to a study by the Coalition on the Academic Workforce, a group of education and research associations.

The number of part-time faculty members teaching undergraduate courses has triggered controversy, particularly as families face higher tuition costs. California Gov. Jerry Brown has called for tenured professors to teach more courses.

The part-timers’ median pay per course at all two-year and four-year schools in 2010 was just $2,700, the coalition survey found.

Some part-time professors don’t depend on income from teaching. They lead a class or two a year as a community service or to supplement income from flourishing careers elsewhere. For example, a successful accountant may teach a class on tax policy and an orchestra member may train a small group of music students.

Under federal rules, all part-timers gain representation if 30% of eligible faculty members sign union cards and then a majority of voters approve it in a confidential ballot election supervised by the NLRB.

Union organizing campaigns are underway at California Institute of the Arts, known as CalArts, in Valencia and Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Efforts have stalled at the University of La Verne after tension between the union and administrators, and the Laguna College of Art and Design administration is challenging its tight election results to the NLRB.

At CalArts, where no faculty member has tenure, SEIU Local 721 is trying to organize both full-time and part-time teachers.

President Steven D. Lavine said he is concerned that unionization “is likely to make us slower, less agile and more vulnerable to the economy” at a time of rapid changes and increased financial pressures in higher education.

CalArts, which enrolls about 1,500 students, uses its full-time faculty to teach about 75% of its classes, more than most other art schools, he said. Many part-time teachers are specialists who come in for one class, such as Hollywood animation experts for whom “teaching at night is a kind of service to the profession, not a source of their livelihood.”

Still, Lavine acknowledged the tough situation facing part-timers who rely on the $5,000 or $6,000 stipend per class and who travel from college to college to support themselves.

Jen Hofer, a part-time CalArts faculty member in the master’s degree program in writing for the last decade, said she earns about $15,000 a year there by teaching one course each semester, mentoring graduate students and supervising a student-run public reading series, plus other duties. She also works as a freelance interpreter and a translator and teaches one class a year at Otis.

Hofer said she has become active in the pro-union movement because “I’ve shown many years of commitment to the well-being of the school and my students and want to feel this institution is committed to me and my colleagues in the same way.”

Twitter: @larrygordonlat

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.