Justice, 64 years later

- Share via

SEATTLE — It was a crime so improbable that many had trouble believing it could have happened at all: Three black soldiers stood accused of lynching an Italian prisoner of war, found dangling from a wire on an obstacle training course at Ft. Lawton in the middle of World War II.

The subsequent trial of the three men, along with 40 other black enlistees charged with rioting, became the largest and longest Army court-martial of the war, and the only recorded instance in U.S. history in which black men stood trial for a mob lynching.

By the time it was over, 28 men had been convicted on rioting charges and two of them were also found guilty of manslaughter in connection with the 1944 hanging.

Despite their protests of innocence -- and the government’s own secret investigation showing the prosecution’s case was poisonously flawed -- the men were sentenced to hard labor and forfeiture of military pay and benefits, and were given dishonorable discharges.

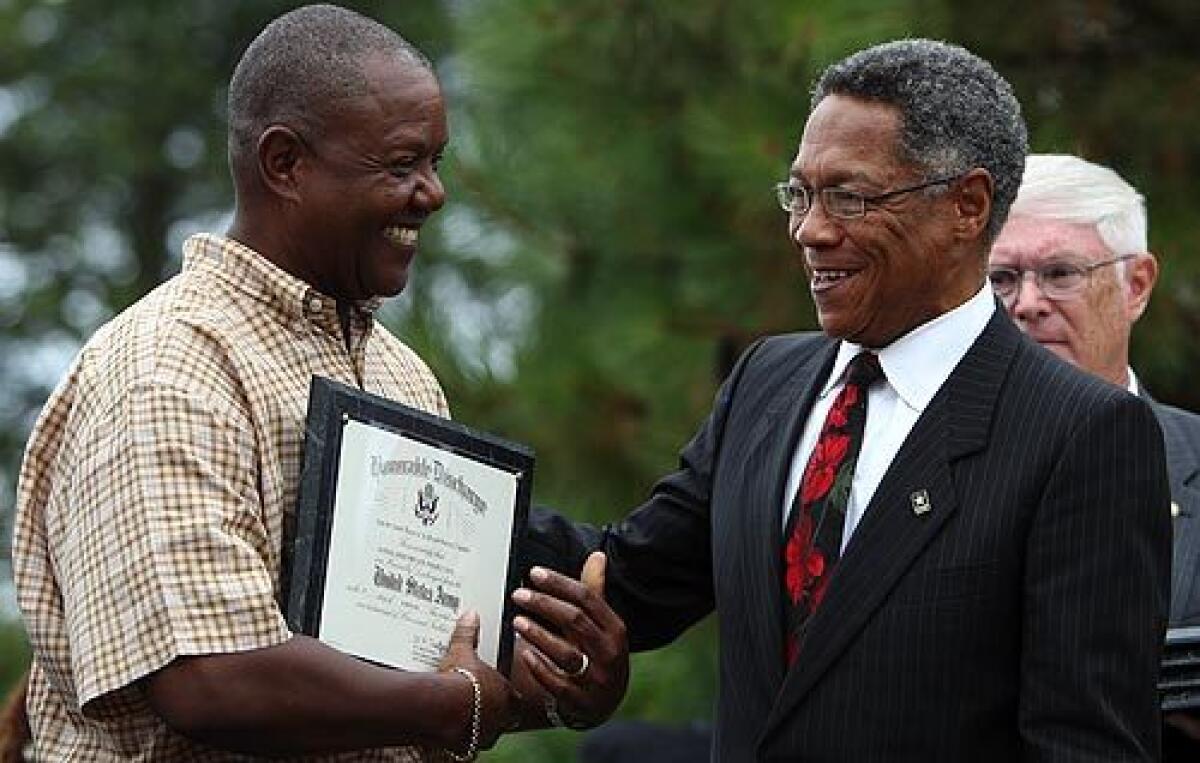

Twenty-six of the men went to their graves with the stain of wartime dishonor still on their records. It wasn’t until Saturday, in a low-key ceremony on a wide lawn at the Army base in Seattle, that history switched gears. A senior Army official handed out certificates setting aside the convictions and converting the discharges to honorable status, in recognition -- 64 years after the fact -- that prosecutors’ “egregious error” had resulted in a trial that was “fundamentally unfair.”

“I grieve for an Army that failed to honor its own values at Ft. Lawton,” said Ronald J. James, an assistant Army secretary, as he handed out the certificates to surviving family members.

“The Army is genuinely sorry. I am sorry. Sorry for your husbands, loved ones, fathers and grandfathers, for the lost years of their lives,” James said, calling the ceremony a “long-overdue vindication.”

Not one of the soldiers were on hand to accept the apology. One of the two still living did try to attend -- 83-year-old Samuel Snow from Leesburg, Fla. -- but he was hospitalized with heart palpitations in downtown Seattle just hours before the observance.

“My father never held any animosity,” said Snow’s son, Ray.

“He said, ‘Son, God has been good to me. If I hold this in my heart, then I can’t walk in forgiveness.’ Really, it energized him. It was the fuel that drove him: ‘Bring on all the things that are supposed to stop me from achieving.’ This was all liquid oxygen for him.”

The case of the Ft. Lawton 28 had been little known in recent years, though the court-martial in 1944 was widely covered in the news at the time.

It wasn’t until former television journalist Jack Hamann came upon the Italian soldier’s grave in 1986 and began years of research that archival material was uncovered, demonstrating fatal flaws in the government’s case -- and pointing to the likelihood that the Italian prisoner was killed by a white man.

Immediately after the lynching, the Army inspector general had conducted an exhaustive investigation that raised major questions about the evidence against the accused.

But the Army had appointed only two defense lawyers to handle all 43 men, giving them 10 days to prepare their case, and they were not permitted to see the report.

The prosecutor was Col. Leon Jaworski, who in 1973 became the special prosecutor in the Watergate case involving the administration of President Nixon.

“Jaworski disingenuously -- and, it’s clear now, illegally and unethically -- said, ‘Sorry, that’s not what you think it is, and you can’t have it.’ He fought, and got the court to agree not to let it in,” Hamann said in an interview. Jaworski died in 1982.

Hamann wrote a 2005 book about the case, “On American Soil.”

Based in large part on the evidence disclosed in the book, the Army Board for Correction of Military Records reviewed the case last year and ruled unanimously to overturn the convictions and grant retroactive honorable discharges.

“I don’t think very often they come out and say our largest and longest court-martial of this giant war, World War II, was fatally flawed,” Hamann said.

“But the Army has been a driver of this, by getting out ahead of it and saying, ‘We want to let our constituents know we’re not hiding behind this. We’ve read the evidence, we agree, we checked it out ourselves.’ ”

The junior defense counsel in the case, Howard Noyd, now 93, said he and his partner had known from the beginning that “justice was sacrificed” and his clients were wrongly charged.

“It’s just a remarkable story. I didn’t expect we would ever come to final justice,” Noyd said.

Walt Prevost, 65, the owner of a pharmacy in Watts, traveled to Seattle on behalf of his late father, Willie Prevost, who he said never talked about the case before his death in 1998.

“I talked to a lot of the other families, and they all say the same thing: They never talked about it. We knew absolutely nothing about [my father’s] Army career. It was something he was really impacted by in an adverse way, so he would never talk about it,” Prevost said.

“But I would say my family suffered severely as a result of the Ft. Lawton tragedy,” he said. His mother was forced to raise her four children with no income or Army benefits while his father was in prison, he said.

Hamann said that though most of the prison terms were relatively short, the convicted soldiers would have been affected their entire lives.

“You’re talking about 50 years of no GI Bill, no VA, no ability to get a civil service job with that dishonorable discharge,” Hamann said.

Some reparations are being offered: back pay for the prison time. Snow was sent a $725 check, which he didn’t bother to cash.

Rep. Jim McDermott (D-Wash.) is pushing legislation that would grant the soldiers full reparations.

“The main thing is he never got to do the things he wanted to do,” said Beverly Evans, a South Los Angeles resident whose father, Luther Larkin, was convicted in the lynching. He died a month before she was born, in 1948.

James, the assistant Army secretary, ended his calm but emotional address with a declaration that he would not end it as most such speeches conclude.

“The usual closing is something like ‘God bless the Army, and God bless the United States of America,’ but frankly that doesn’t seem right or appropriate for this time -- I have unpaid debts and unpaid dues,” James said.

“Therefore, I would like to close by saying: God bless Samuel Snow, God bless the Ft. Lawton 28, and God bless your family and friends.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.