A question lingers in Baton Rouge: What good is unity without change?

- Share via

Reporting from Baton Rouge, La. — A young man takes the podium and jokes about the summer heat. His hair is swept to the side, his shadow of a beard perfectly trimmed, mahogany leather shoes balanced strikingly against his cobalt suit, the very picture of a politician.

He is the student body president at Louisiana State University. His father, the former Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal’s go-to attorney for defending the state, is a partner in a firm that handled more than two dozen state cases.

He speaks as dozens have before him, in Dallas, in Phoenix, in Milwaukee, in Cleveland, in North Charleston, S.C., about the need for unity. On Sunday, a gunman ambushed and killed three police officers here, in a city already on edge after days of angry clashes between protesters and police.

“The wounds are deep, there is no doubt about it. But they will be repaired because they have to be,” said Zach Faircloth, addressing a vigil Wednesday hosted by the university’s student government. “LSU forever. Baton Rouge forever.

“God bless America.”

“Thank you.”

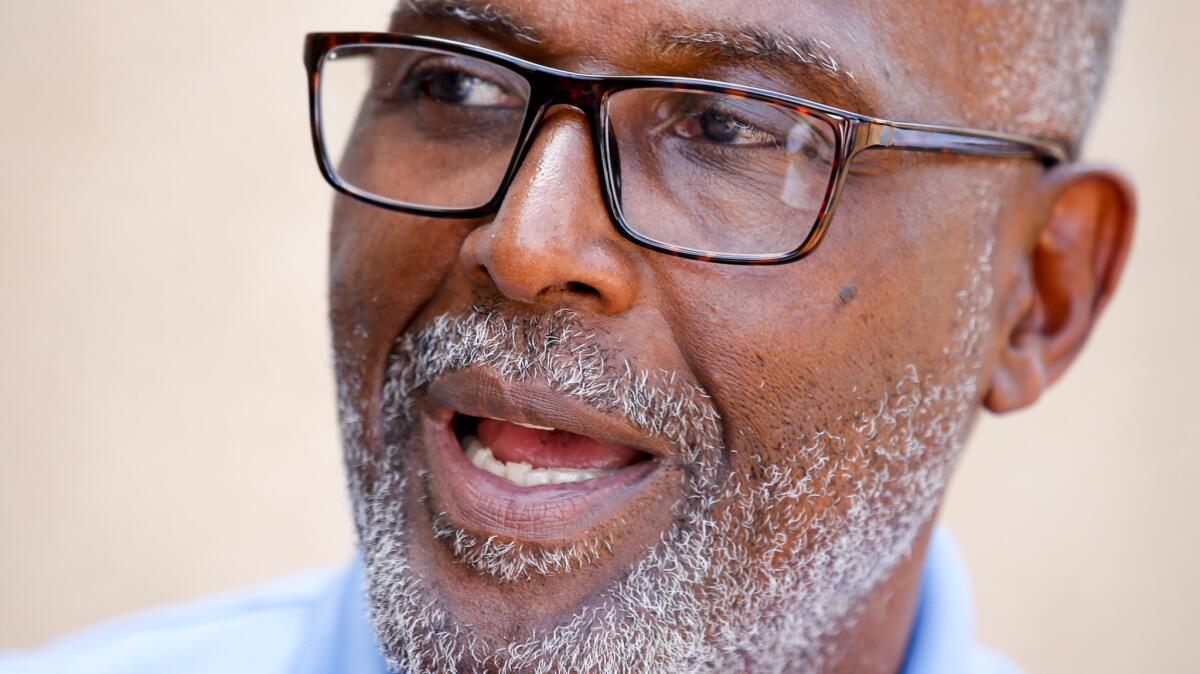

Then, the Rev. Raymond Jetson of Star Hill Baptist Church was called up. He hadn’t discussed his speech with any of the people on stage. Certainly not with Faircloth.

“I am delighted and befuddled by calls for healing and unity as if it were an event,” he said. “It is a process. Healing requires that we acknowledge the illness.”

The murmur of conversation in the crowd of about 200 dropped a few decibels. Purple-and-yellow Louisiana State University banners hanging from the flagpoles snapped in the breeze. Otherwise, it was quiet.

“It requires realizing that something is fundamentally wrong,” Jetson said.

The crowd remained nearly silent, and when he was done, they clapped.

After destructive protests against police violence, the kind that often end with protesters throwing bottles and police in riot gear fighting back with tear gas, there are invariably calls for unity.

“How can a house divided ever stand?” the Rev. Anthony Smith of tiny Iowa City, Iowa, asked after the violent protests in Ferguson, Mo., two years ago.

“This tree will serve as a living symbol of peace, justice and unity,” New York City Councilwoman Debi Rose said Sunday, after dedicating a myrtle tree to the memory of Eric Garner, who died two years ago while police officers attempted to arrest him for selling untaxed cigarettes.

“That was the first time I felt any sort of campus unity since this stuff has started happening,” Johns Hopkins University freshman Kyra Meko told the campus newsletter last year after the violent protests in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody.

“The police, it’s not them versus us or us versus them. We are them, they are us, and that’s the message of unity we need to discuss,” conservative televangelist Mark Burns said on CNN’s “Erin Burnett OutFront” the day of the attack on Baton Rouge police.

But what good is unity, Jetson asked, without change first?

Jetson, who is black, has a son who will be a freshman at LSU in the fall.

Jetson cannot quite articulate what he hopes LSU and Baton Rouge will look like by the time his son is a senior. A more integrated city, certainly. But also one ready to hear and respond to difficult truths about segregation, poverty and unequal treatment by law enforcement.

“What led [Alton Sterling] to be selling illegal CDs at midnight to support his family?” Jetson wondered, speaking after the vigil with The Times about a black man shot to death by Baton Rouge police this month. “We need to be discussing that.”

The grief is still fresh here. Three police officers are dead and a fourth hanging to life. But along with framed photos of the officers and construction paper signs proclaiming “blue lives matter,” the turmoil that wracked this city after officers killed Sterling has not retreated far, and now is still alive. And it’s pushing back again.

Since the ambush on Sunday that ended when officers shot and killed gunman Gary Eugene Long, protesters asserting inequities in the policing of the city’s black population have quietly attended vigils for the slain officers and maintained a low profile.

Subtly and quietly, however, their protest endures. The results have been uneven in a city on edge, where a threat of violence this week scared managers into temporarily closing a Wal-Mart on the outskirts of town, and protesters drew the wrath of the local police union by wearing T-shirts splattered with fake blood.

Jetson said he understands the potential to rattle nerves here by using the language of an ongoing protest movement at a purportedly neutral memorial that was meant to pay respect to both the slain officers and those killed by police.

“The delivery, doing it respectfully, not singling out one group of people, that is how we can talk about these issues,” he said. Then he repeated a mantra from his speech.

“Pretending that it does not exist will not make it go away.”

ALSO

Nephew provides glimpse into the paranoid world of Baton Rouge gunman Gavin Long

Florida police shoot autistic man’s caretaker as he lies in street with hands in the air

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.